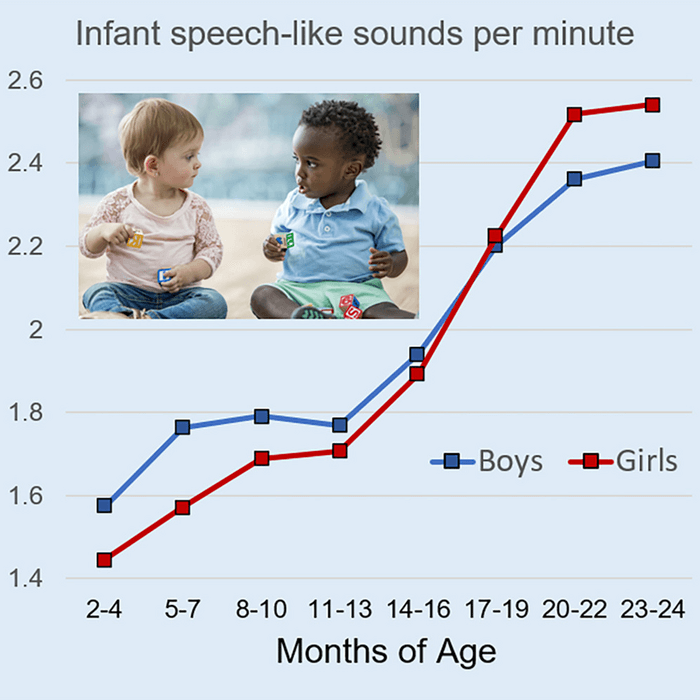

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Baby boys tend to vocalize more in their first year than girls, according to a comprehensive new study. This early communication includes sounds like squeals, vowel-like utterances, growls, and short pseudo-word sounds such as “ba” and “aga.” As babies grow, these sounds evolve into early words, phrases, and eventually full sentences.

While some infants naturally vocalize more than others, on average, boys express about 10 percent more sounds in their first year than girls. This finding contradicts the long-held belief that girls have a consistent advantage over boys in language development. However, by the end of the second year, girls surpassed boys, making seven percent more sounds.

Researchers from the University of Memphis suggest this trend could be related to an evolutionary theory that infants vocalize early to express their well-being and enhance survival chances. The researchers propose that the gender difference could be because boys are more likely to die in their first year than girls.

The research involved over 450,000 hours of full-day recordings of 5,899 infants. The team studied the children’s precursors to speech, known as “protophones,” using a device about the size of an iPod. These recordings automatically analyzed a period covering the first two years of life.

“While it’s widely believed that females have a small but noticeable advantage over males in language development, we found that in the first year, boys produce more speech-like vocalizations than girls,” says Dr. Kimbrough Oller from the University of Memphis in a media release. “Although boys vocalize at higher rates in the first year, girls catch up and surpass boys by the end of the second year.”

“This is the largest sample size for any study on language development conducted to our knowledge. Our hypothesis is that since many male infant deaths occur in the first year, boys may face particularly high selection pressure to produce vocal fitness signals,” notes Dr. Oller. “We anticipate that caregivers will respond positively to the speech-like sounds, indicating that effective vocalizations by the baby elicit genuine feelings of fondness and willingness to invest in the infant’s well-being.”

The researchers are also interested in understanding how caregivers react to the speech-like sounds of boys and girls. However, they noted that it might be challenging to discern the sex of infants based solely on their vocalizations.

The research is published in the journal iScience.

Baby talk is important for parents too

When Mommy and Daddy use baby talk, a 2018 study finds it’s more than just child’s play. That repetitive, cute speech pattern that seems to come so naturally to most parents, grandparents, and caregivers also speeds up vocabulary development and language skills.

Researchers with the University of Edinburgh found that the amount of exposure infants have to baby talk corresponds to an increase in their vocabulary. Linguists at the university recorded speech directed at 47 infants, looking for patterns that characterize baby talk words. Baby talk words often end in a “y” sound — bunny, tummy, horsie — or use repetitive sounds, such as choo-choo, night-night, or yum-yum.

They found that 9-month-old babies who heard language liberally sprinkled with such words as “binky” or “paci” for pacifier and “baba” for bottle had picked up new words faster in the developmental period between nine and 21 months.

Parents also talk more to talkative children

The new study also has interesting implications when it comes to how much a parent or caregiver talks with their child. In 2022, researchers at Duke University were still working under the impression that infant girls vocalize more than baby boys. However, they found that caregivers tend to talk more to young children who themselves are already talking, regardless of gender.

“This study provides evidence that children actively influence their own language environments as they grow,” says lead study author Shannon Dailey, Ph.D., a Duke postdoctoral scholar, in a university release.

Study authors also determined that girls’ bigger vocabularies were not due to them speaking earlier in life. While females tend to say their first real words around their first birthday, boys aren’t all that far behind, with males usually beginning to speak around 13 months-old.

South West News Service writer Pol Allingham contributed to this report.