EVANSTON, Ill. — The “silent hazard” of climate change appears to be causing buildings in many major cities around the world to sink, a new study warns. Researchers have discovered that the ground is undergoing deformation, posing a threat to large apartment and office buildings that were not originally designed to withstand such changes.

Older cities’ buildings are particularly vulnerable, according to scientists who claim, “you don’t need to live in Venice to live in a city that is sinking.”

The groundbreaking study is the first to quantify the impacts of subsurface climate change on civil infrastructure. For the first time, researchers from Northwestern University have connected underground climate change with the shifting ground beneath urban areas in the study published in the journal Communications Engineering.

The team explains that as the ground warms, it distorts. This leads to excessive movement – due to expansions and contractions – and even cracking in building foundations and the surrounding ground, ultimately affecting a structure’s long-term performance and durability.

The research team also discovered that rising temperatures might have been responsible for previous building damage and cautioned that these problems will persist for years to come.

However, the researchers also see this threat to our infrastructure as a potential opportunity. They propose that harnessing the waste heat emitted from subterranean facilities like transportation systems, parking garages, and basements could help mitigate the effects of underground climate change while turning this heat into an unexploited thermal energy resource.

“Underground climate change is a silent hazard,” says Northwestern’s Alessandro Rotta Loria in a university release. “The ground is deforming as a result of temperature variations, and no existing civil structure or infrastructure is designed to withstand these variations. Although this phenomenon is not dangerous for people’s safety necessarily, it will affect the normal day-to-day operations of foundation systems and civil infrastructure at large.”

“Chicago clay can contract when heated, like many other fine-grained soils,” Rotta Loria continues. “As a result of temperature increases underground, many foundations downtown are undergoing unwanted settlement, slowly but continuously. In other words, you don’t need to live in Venice to live in a city that is sinking — even if the causes for such phenomena are completely different.”

Urban areas worldwide are experiencing alarming rates of ground warming due to heat continuously diffusing from buildings and underground transportation. Prior studies have reported that city subsurface warming ranges between 0.1 to 2.5 degrees Celsius per decade.

Termed as “underground climate change” or “subsurface heat islands,” this phenomenon is known to cause ecological problems such as groundwater contamination, and health issues including asthma and heatstroke. However, its impact on civil infrastructure has remained largely unexplored until now.

“If you think about basements, parking garages, tunnels and trains, all of these facilities continuously emit heat,” the researcher explains. “In general, cities are warmer than rural areas because construction materials periodically trap heat derived from human activity and solar radiation and then release it into the atmosphere. That process has been studied for decades. Now, we are looking at its subsurface counterpart, which is mostly driven by anthropogenic activity.”

Rotta Loria’s team installed a network of over 150 temperature sensors throughout Chicago, both above and below ground, including in building basements, subway tunnels, and underground parking garages. For comparison, sensors were also installed in Grant Park, a green space located along Lake Michigan, away from buildings and transportation systems.

Data indicated that the city’s underground temperatures are often 10 degrees higher than those beneath Grant Park. Underground structures can even have air temperatures 25 degrees higher than undisturbed ground temperatures, according to Dr. Rotta Loria.

He explains that heat diffusing towards the ground puts significant stress on materials that expand and contract with changing temperatures.

“We used Chicago as a living laboratory, but underground climate change is common to nearly all dense urban areas worldwide,” Rotta Loria says. “And all urban areas suffering from underground climate change are prone to have problems with infrastructure.”

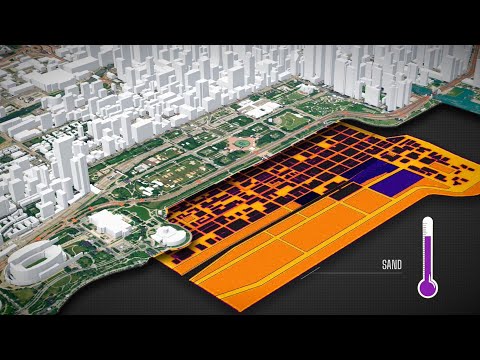

After collecting temperature data for three years, Dr. Rotta Loria created a 3D computer model to simulate how ground temperatures have evolved since 1951 – the year Chicago completed its subway tunnels – up to the present day. The model projected how temperatures will change up until 2051.

The simulations showed that warmer temperatures could cause the ground to expand upwards by as much as 12 millimeters (0.47 inches), and to contract and sink under the weight of buildings by as much as eight millimeters (0.31 inches). Dr. Rotta Loria notes that while these changes might seem minute and are unnoticeable to humans, they exceed what many building components and foundation systems can withstand without jeopardizing their operational capabilities.

“Based on our computer simulations, we have shown that ground deformations can be so severe that they lead to problems for the performance of civil infrastructure,” the study author reports. “It’s not like a building will suddenly collapse. Things are sinking very slowly. The consequences for serviceability of structures and infrastructures can be very bad, but it takes a long time to see them. It’s very likely that underground climate change has already caused cracks and excessive foundation settlements that we didn’t associate with this phenomenon because we weren’t aware of it.”

“In the United States, the buildings are all relatively new,” Rotta Loria notes. “European cities with very old buildings will be more susceptible to subsurface climate change. Buildings made of stone and bricks that resort to past design and construction practices are generally in a very delicate equilibrium with the perturbations associated with the current operations of cities. The thermal perturbations linked to subsurface heat islands can have detrimental impacts for such constructions.”

“The most effective and rational approach is to isolate underground structures in a way that the amount of wasted heat is minimal,” the Northwestern researcher concludes. “If this cannot be done, then geothermal technologies offer the opportunity to efficiently absorb and reuse heat in buildings. What we don’t want is to use technologies to actively cool underground structures because that uses energy. Currently, there are a myriad of solutions that can be implemented.”

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.

You might also be interested in:

- ‘Significant’ sinking ground discovered in Houston suburbs

- Cities are sinking under their own weight, increasing danger from rising sea levels

- Global warming: Here’s where climate change could lead to record-setting heatwaves soon