LA JOLLA, Calif. — Have you ever felt hungrier when it’s cold outside? Neuroscientists from Scripps Research have discovered why. They’ve pinpointed specific brain circuits that push mammals, including humans, to eat more when they feel chilly.

Mammals naturally burn extra energy to keep their body warm when it’s cold outside. This surge in energy usage makes them hungrier, even though exactly how this worked remained a mystery. However, researchers have now identified a group of brain cells in mice that act like a “switch” for this cold-triggered hunger. The findings could open new avenues for treatments focusing on metabolism and weight loss.

“This is a fundamental adaptive mechanism in mammals and targeting it with future treatments might allow the enhancement of the metabolic benefits of cold or other forms of fat burning,” says study senior author Dr. Li Ye, an associate professor and the Abide-Vividion Chair in Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Scripps Research, in a media release.

While it’s known that cold temperatures lead us to burn more energy to stay warm, practices like cold water immersion, known as “cold therapy,” are being considered for weight loss and boosting metabolic health. However, there’s a catch. Our bodies’ ancient reactions to cold aren’t designed to help us lose weight. Back when food was often scarce, getting too thin could have been deadly. So, when we’re cold (just like when we’re on a diet or exercising), we tend to get hungrier to counteract weight loss. Researchers decided to uncover the brain’s wiring behind this hunger boost.

Their first clue? Mice exposed to a sharp drop in temperature, from 73 degrees Fahrenheit down to 39 degrees Fahrenheit, didn’t start hunting for food immediately. It took about six hours, suggesting the hunger wasn’t a direct reaction to the cold.

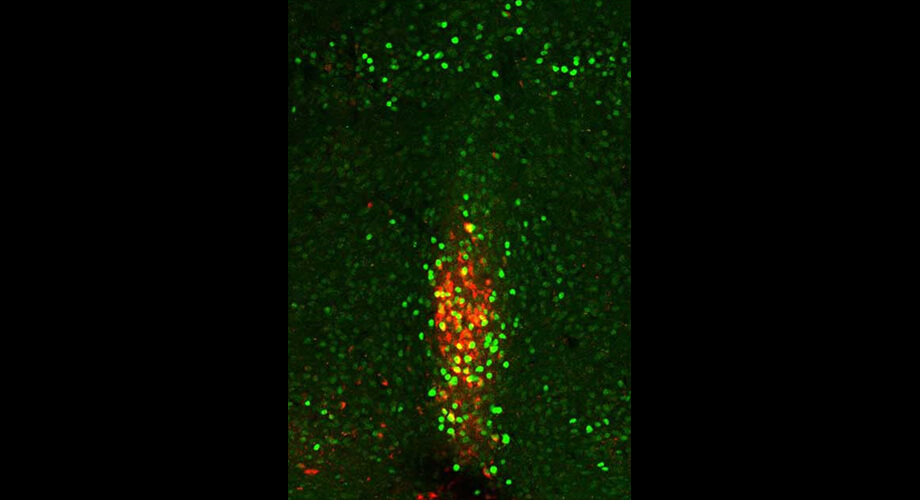

Using advanced imaging techniques, the team examined which brain cells lit up during cold versus warm periods. They found that in cold conditions, a part of the brain known as the thalamus displayed more activity.

Narrowing it down further, they discovered a unique cluster of neurons in the thalamus, named the xiphoid nucleus. These neurons became super active in the cold, right before the mice began searching for food. If food was limited when the cold hit, the xiphoid nucleus was even more active. This indicated these neurons were more attuned to energy shortages from the cold than the cold itself.

When scientists activated these neurons, the mice’s hunger increased. If they blocked them, hunger dropped. This only worked in cold settings, though, meaning there’s a separate cold signal influencing appetite.

Lastly, the team found these xiphoid nucleus neurons connect with another part of the brain: the nucleus accumbens. This area plays a crucial role in regulating behavior based on rewards, including eating.

According to Ye, the big takeaway here could be in weight loss: if we can block this cold-induced hunger, simply being cold might help people shed pounds more effectively.

“One of our key goals now is to figure out how to decouple the appetite increase from the energy-expenditure increase,” notes Ye. “We also want to find out if this cold-induced appetite-increase mechanism is part of a broader mechanism the body uses to compensate for extra energy expenditure, for example after exercise.”

The study is published in the journal Nature.

You might also be interested in:

- Live cold, die old? Lower body temperature linked to a longer life

- ‘Beige fat’ may hold the key to reversing age-related weight gain

- Cryostimulation therapy: How 2 minutes in extreme cold can help obese people lose weight