HANOVER, N.H. — Today, the phrase “all roads lead to Rome” is nothing more than an expression, but go back a few thousand years and the saying rang quite true in the literal sense. The Roman Empire was the absolute center of the ancient world, and its borders extended throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Now, declassified Cold War-era photography has revealed hundreds of previously undocumented Roman forts stretching from western Syria to northwestern Iraq.

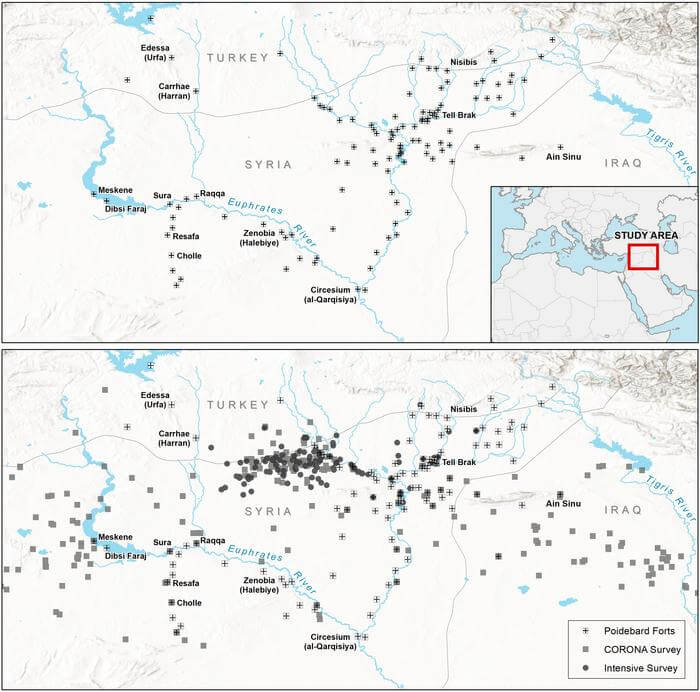

The story of these findings begins 2,000 years ago, when the Roman Empire built forts across the northern Fertile Crescent. Fast forward to more modern times, and in the 1920s, Father Antoine Poidebard successfully documented 116 of those forts using one of the first-ever aerial surveys conducted using a World War I-era biplane. At the time, Father Poidebard suspected that the forts had been built north to south in order to establish an eastern boundary of the Roman Empire.

Today, researchers at Dartmouth College analyzed declassified Cold War satellite imagery, revealing an astounding 396 additional and previously undocumented Roman forts in the same area. However, these forts were constructed from east to west. This latest work refutes Poidebard’s claim that the forts were located along a north-south axis by documenting that the forts extended all the way from present-day Mosul on the Tigris River to Aleppo in western Syria.

“I was surprised to find that there were so many forts and that they were distributed in this way because the conventional wisdom was that these forts formed the border between Rome and its enemies in the east, Persia or Arab armies,” says lead author Jesse Casana, a professor in the Department of Anthropology and director of the Spatial Archaeometry Lab at Dartmouth, in a media release. “While there’s been a lot of historical debate about this, it had been mostly assumed that this distribution was real, that Poidebard’s map showed that the forts were demarcating the border and served to prevent movement across it in some way.”

To make these incredible discoveries, the research team made use of imagery from the Cold War-era CORONA and HEXAGON satellites, collected between 1960 and 1986. Most of those photos are a part of the open-access CORONA Atlas Project. Thanks to this access, Prof. Casana and the team were able to develop superior methods for correcting the data and even made it available online.

More specifically, the research team assessed satellite imagery spanning roughly 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 square miles) of the northern Fertile Cresent. That area is a place where sites show up particularly well and are archaeologically significant, according to Prof. Casana. First, study authors mapped 4,500 known sites, then moved on to systematically documenting every other site-like feature in each of the nearly five by five kilometer (3.1 mile by 3.1 mile) survey grids. This approach led to the addition of 10,000 new undiscovered sites to the database.

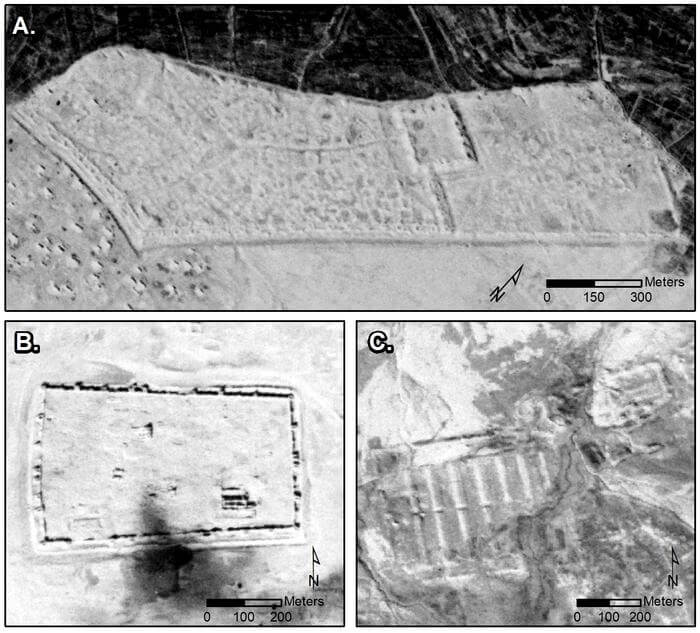

When the database was first created, Prof. Casana put together morphological categories based on the different features evident in the imagery, making it possible for the research team to run queries. One of those categories was Poidebard’s forts, or distinctive squares measuring approximately 50 by 100 meters (.03 x .06 miles), roughly comparable to the size of about half a soccer field.

Those forts would have been big enough to house and accommodate soldiers, horses, and camels. Judging from the satellite imagery, some forts even featured lookout towers in the corners or sides. The forts would have been originally constructed using stone and mud-brick, or entirely mud-brick. That means eventually, the forts probably melted into the ground.

While the vast majority of the forts first seen and documented by Poidebard were either destroyed or obscured by agriculture, land use, or other activities between the 1920s and 1960s, researchers were indeed able to locate 38 of Poidebard’s 116 forts – in addition to the newly found 396 forts.

Among those 396 “new” forts, 290 were located in the study region and another 106 were found in western Syria, in Jazireh. Besides just identifying forts similar to the walled fortresses Poidebard found a century ago, study authors also identified forts with interior architecture features and others built around a mounded citadel.

“Our observations are pretty exciting and are just a fraction of what probably existed in the past,” Prof. Casana concludes. “But our analysis further supports that forts were likely used to support the movement of troops, supplies, and trade goods across the region.”

The study is published in the journal Antiquity.

You might also be interested in:

- Ancient Roman glass has evolved into stunning crystals! Could they power modern electronics?

- Amazing archaeological finds dating back to 10,000 BC unearthed just 8 miles from Stonehenge

- How has ancient Roman cement stood test of time so well? Scientists finally have an answer after 2,000 years!