RALEIGH, N.C. — Different dog breeds exhibit varying levels of pain sensitivity, but these differences don’t always align with the commonly held beliefs about breed-specific pain. A recent study conducted by researchers at North Carolina State University reveals how a dog’s temperament, specifically its interaction with strangers, can influence the way veterinarians perceive that breed’s pain sensitivity.

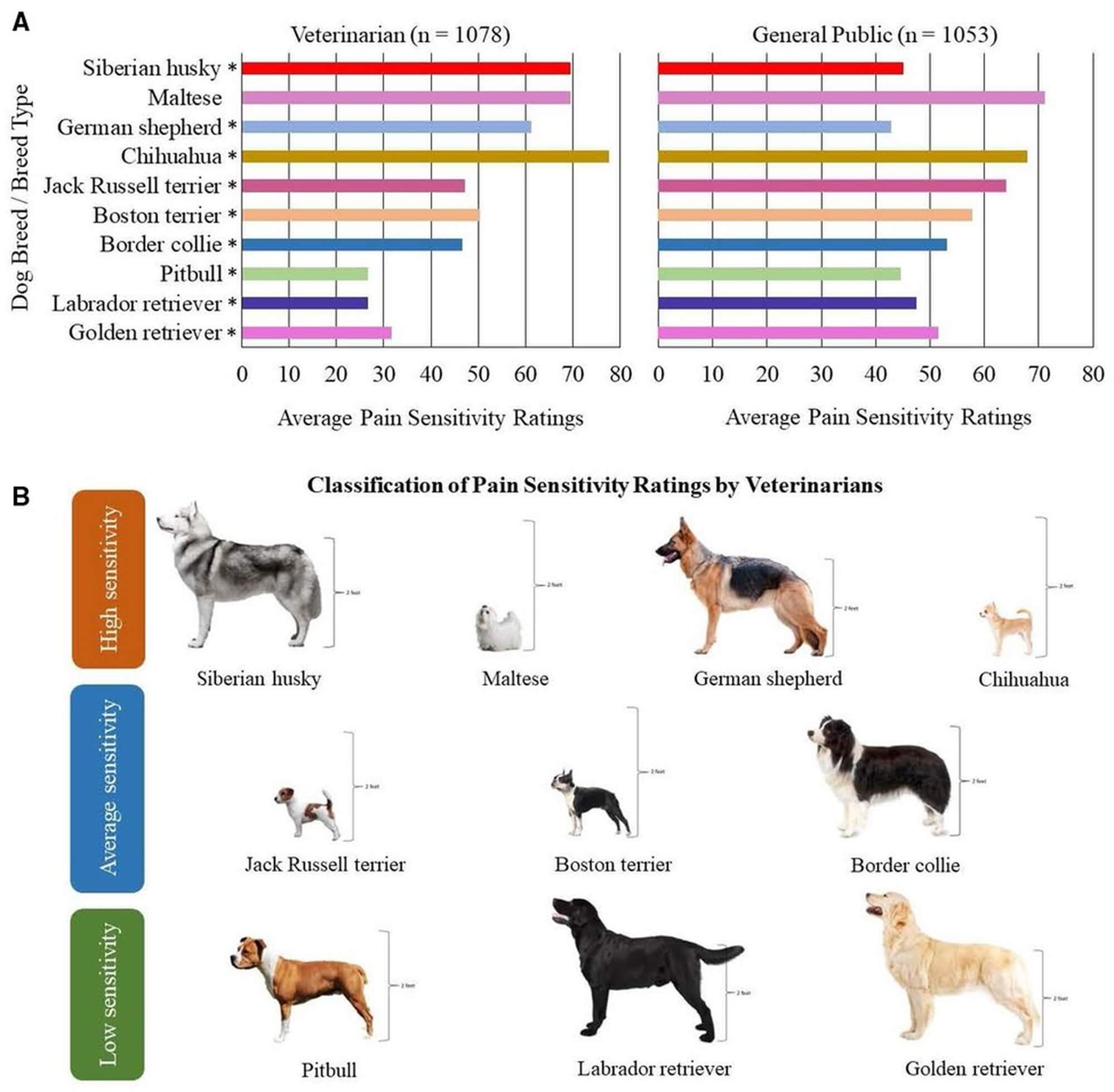

“Veterinarians have a fairly strong consensus in their ratings of pain sensitivity in dogs of different breeds, and those ratings are often at odds with ratings from members of the public,” says Margaret Gruen, associate professor of behavioral medicine and co-corresponding author of the study.

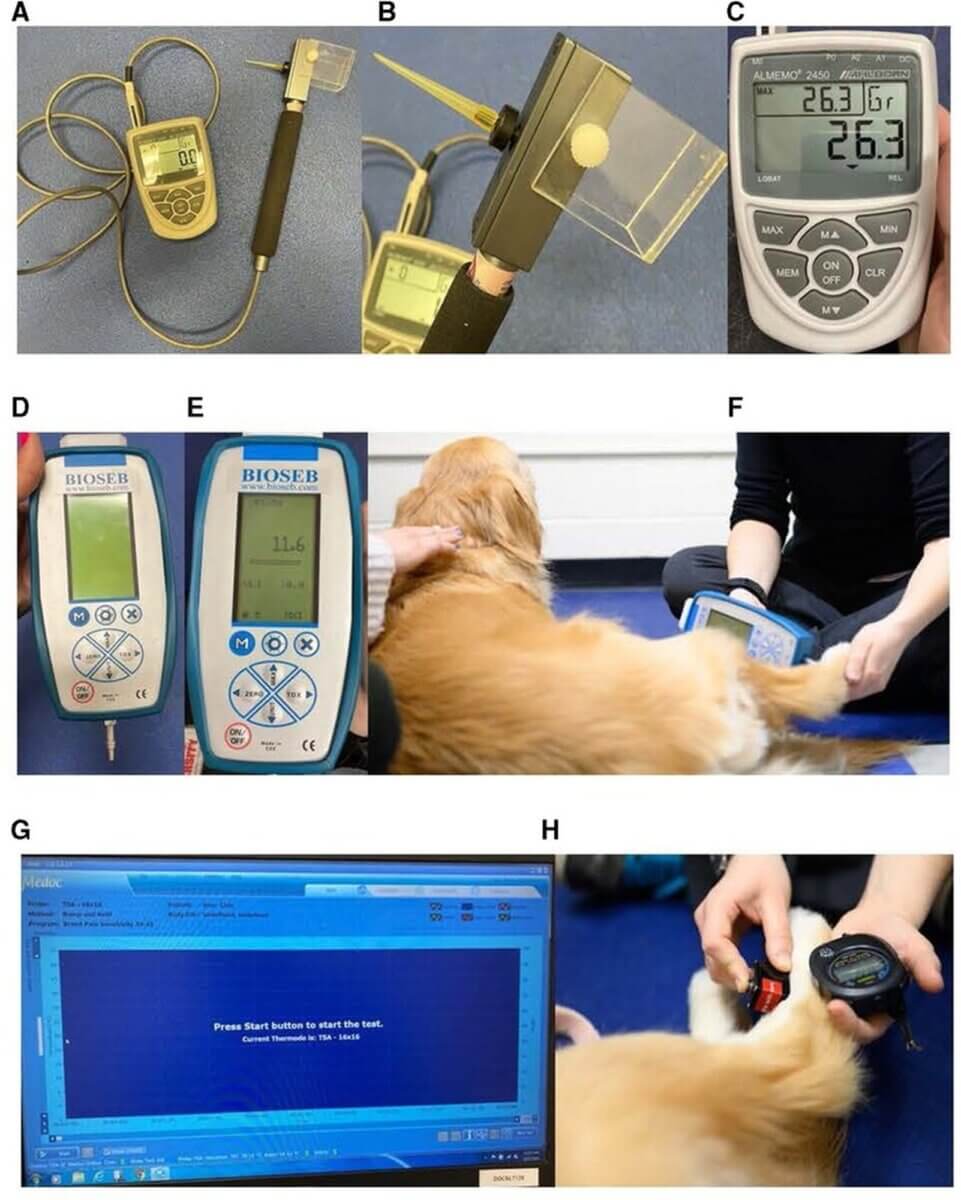

The study investigated whether there is a correlation between perceived breed pain sensitivity and actual pain thresholds in dogs. Researchers examined 149 adult healthy dogs from 10 different breeds that had been subjectively rated by veterinarians as having high, average, or low pain sensitivity. Pain sensitivity was measured using methods adapted from human clinical medicine, involving pressure and temperature tests applied to the dogs’ back paws. Emotional reactivity tests were also conducted to assess the dogs’ response to unfamiliar objects and people.

The results indicated that there are indeed breed-specific differences in pain sensitivity thresholds among dogs. However, these differences did not always align with the rankings provided by veterinarians. For example, Maltese dogs demonstrated a high sensitivity threshold, consistent with veterinarians’ perception. In contrast, Siberian huskies were thought to be highly sensitive by veterinarians, but their pain tolerance was found to be in the mid-range. Interestingly, some larger breeds believed to be sensitive actually showed average-to-high pain tolerance.

The study also revealed a potential link between a dog’s emotional reactivity and veterinarians’ pain tolerance ratings for certain breeds. Dogs that were less likely to engage with novel objects or show stress during interactions with strangers were sometimes rated as having lower pain tolerance. This suggests that a dog’s stress levels and emotional reactivity during a veterinary visit could influence a veterinarian’s perception of pain tolerance for that breed.

The findings of this study suggest that biological differences exist in pain sensitivity between dog breeds, emphasizing the need for individualized treatment approaches. Researchers aim to further explore the biological causes behind these differences, which could lead to more effective breed-specific pain management strategies. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of considering a dog’s anxiety and emotional well-being during veterinary visits, as these factors can influence how pain is perceived.

“On the behavioral side, these findings show that we need to think about not just pain, but also a dog’s anxiety in the veterinary setting,” Gruen says in a university release. “And they can help explain why veterinarians may think about certain breeds’ sensitivity the way they do.”

“This study is exciting because it shows us that there are biological differences in pain sensitivity between breeds. Now we can begin looking for potential biological causes to explain these differences, which will enable us to treat individual breeds more effectively,” adds translation pain research professor Duncan Lascelles.

Overall, this study sheds light on the complex relationship between breed-specific pain sensitivity, veterinarians’ beliefs, and the emotional well-being of dogs during veterinary visits, opening avenues for further research and improved care for our beloved canine companions.

The study is published in the journal Frontiers in Pain Research.

You might also be interested in:

- Friendliest Dogs: Top 5 Breeds Most Recommended By Experts

- Best Joint Supplements For Dogs: Top 5 Products Most Recommended By Experts

- Best Food For Dogs With Sensitive Stomachs: Top 5 Tummy-Friendly Brands Most Recommended By Experts