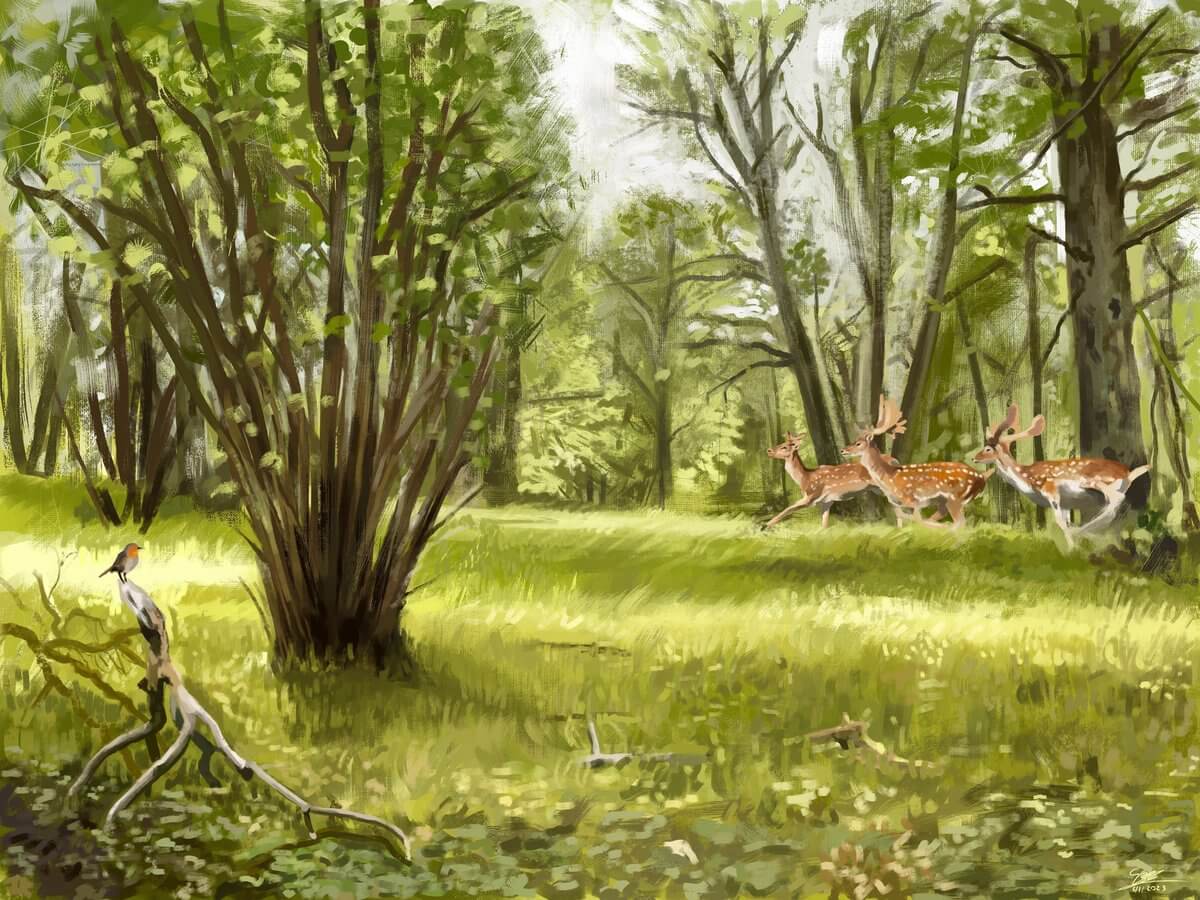

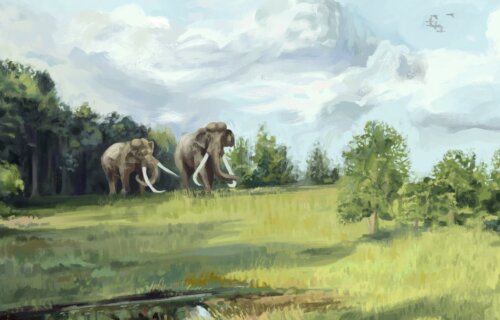

AARHUS, Denmark — Pre-human Europe was not home to dense forests like some might believe. Instead, researchers in Denmark now believe the region had numerous areas of open vegetation. This was largely due to the presence of rhinos and elephants.

Analysis of pollen and twig fragments extracted from rhino fossil teeth indicates that up to three-quarters of Europe might have been covered in open vegetation rather than forests. Additionally, the scarcity of forest beetle fossils, contrasted with an abundance of dung beetles in places like present-day Great Britain, suggests that large mammals significantly shaped the landscape.

Contrary to previous beliefs that post-Ice Age Europe was predominantly dense forests until humans intervened by felling trees — thereby creating diverse landscapes of meadows, heaths, and grasslands — researchers from Aarhus University suggest otherwise. This study reveals that such landscapes predated human arrival.

Focusing on the interglacial period, which spanned from 115,000 to around 129,000 years ago, the research found that between half and three-quarters of the continent’s landscape comprised open or semi-open vegetation. This landscape was likely shaped by the era’s large animals, including elephants and rhinos. It’s noteworthy that humans appeared in Europe approximately 45,000 years ago.

“The idea that the landscape was covered by dense forest across most of the continent is simply not right,” says lead author Elena Pearce, a postdoc at the Department of Biology at Aarhus University, in a media release.

“Now we know that there was a great deal of variation in the landscape. Everything suggests that this variation arose because of large animals affecting the vegetation structure.”

Researchers identified what type of landscapes Europe consisted of all those years ago by using samples of ancient pollen to establish which plants were growing. By doing this, they found a lack of evidence of tall-growing shade trees such as spruce, linden, beech, and hornbeam but a notable prevalence of plants that do not thrive in dense forests, such as hazel.

“Hazel thrives in the open countryside and in open or disturbed forest, and tolerates disturbance from large animals. Whereas species like beech and spruce often are severely damaged or killed by cutting or browsing, hazel can manage without problems. Even if you cut down a hazel, it will still produce lots of new shoots,” explains study co-author Professor Jens-Christian Svenning.

It was ancient hazel pollen that was discovered between the teeth of a rhino fossil.

“Many of the large animals from the interglacial period are now extinct, but we still have bison, horses and oxen,” Dr. Pearce adds.

“Without large animals, natural areas become dominated by dense vegetation, in which many species of plants and butterflies, for example, cannot thrive. Therefore, it’s important we restore large animals to the ecosystems if we are to encourage biodiversity.”

“So the rhinoceros has trudged around eating branches and leaves from hazel bushes. This supports the theory that the large animals have affected the vegetation, perhaps just like historical coppice woodlands. At the same time, marks of its teeth suggest it had foraged a lot on grass and sedges through its life time,” Prof. Svenning continues.

“We know that a lot of large animals lived in Europe at that time. Aurochs, horses, bison, elephants and rhinos. They must have consumed large amounts of plant biomass and thereby had the capacity to keep the tree-growth in check.”

“Of course, it’s also likely that other factors such as floods and forest fires also played a part. But there’s no evidence to suggest that this caused enough disturbance. For example, forest fires encourage pine trees, but mostly we did not find pine as a dominant species,” Svenning reports.

The team is also basing their findings on large animals, such as bison, which have exactly that effect in areas where they are still found in European forests.

“We have looked at a number of finds of beetle fossils from that time in the UK. Although there are beetle species that thrive in forests with frequent forest fires, we found none of them in the fossil data. Instead, we found large quantities dung beetles, and this shows that parts of the landscape have been densely populated by large herbivores,” the study co-author concludes.

You might also be interested in:

- Fossils of our earliest ancestors may be one million years older than scientists thought!

- Stone Age warfare likely swept through Europe 1,000 years earlier than previously thought

- Was Australia colonized 65,000 years before modern humans reached Europe?

South West News Service writer Imogen Howse contributed to this report.

So we didn’t destroy the forests. It was those evil awful elephants and rhinos.