VALLADOLID, Spain — Large-scale warfare in mainland Europe appears to have taken place a millennium earlier than scientists previously believed, a new study reveals. The analysis of over 300 sets of 5,000-year-old skeletal remains from a site in Spain shows that many of these individuals may have been victims of Europe’s earliest known battle, dating back to the end of the Stone Age.

The study highlights the significant number of casualties and the disproportionately high percentage of men affected. These findings suggest that the injuries were the result of a conflict that could have spanned several months.

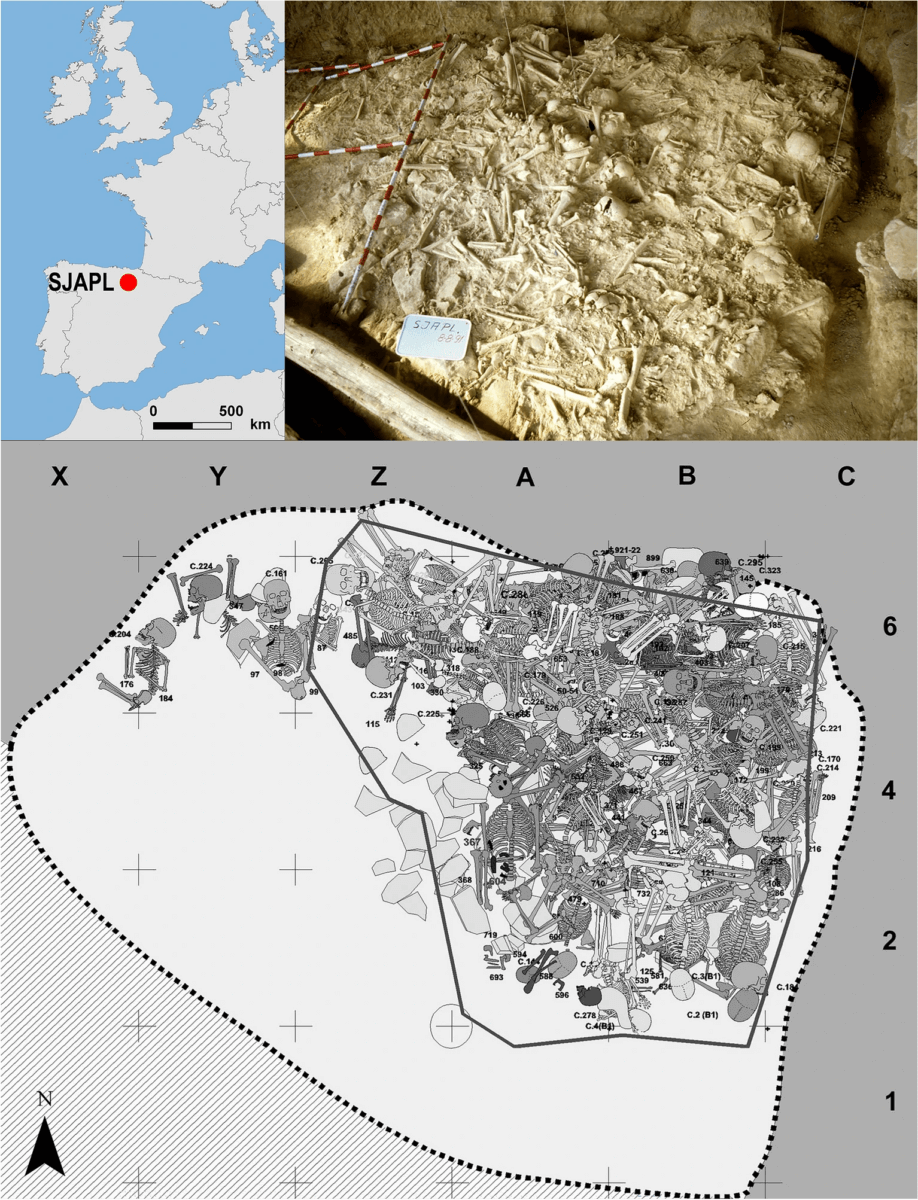

Researchers at the University of Valladolid in Spain re-analyzed the skeletal remains of 338 individuals, searching for evidence of both healed and unhealed injuries. All remains were from a mass burial site in a shallow cave in the Rioja Alavesa region of northern Spain, radiocarbon-dated to between 5,400 and 5,000 years ago.

The team discovered 52 flint arrowheads at the site. Previous research indicated that 36 of these showed minor damage consistent with striking a target. Their findings reveal that nearly a quarter of the individuals (23.1%) had skeletal injuries, with 10.1 percent displaying unhealed injuries — a rate substantially higher than estimates for that era.

They also observed that 74.1 percent of the unhealed injuries and 70 percent of the healed injuries were found in adolescent or adult males, a rate significantly higher than that in females. This disparity is not observed at other European Neolithic mass-fatality sites.

The scientists point out that the high number of injuries, particularly among males, and the damage observed on arrowheads indicate that many at the burial site might have been exposed to violence, possibly as casualties of conflict. The significant number of healed injuries implies that the conflict might have extended over several months.

While the exact reasons for this conflict remain uncertain, the research team believes several potential causes, including tensions between different cultural groups in the region during the Late Neolithic period.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

You might also be interested in:

- What was a funeral like 8,000 years ago? Newly discovered child burial site reveals ancient secrets

- Were our ancestors cannibals? Ancient bones reveal early humans ‘butchered one another’

- Egyptian pharaoh executed? Archaeologists reveal new details of ancient king’s death

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.