INDIANAPOLIS — You may have seen Earth’s chemical elements lined up in your chemistry textbook’s periodic table back in school, but have you ever heard how each one sounds? Using a new technique called data sonification, scientists are figuring out how to turn chemistry into music.

Data sonification converted the natural vibrations of molecules into audio. Each element contained its own unique sounds that, when combined, could create a musical composition.

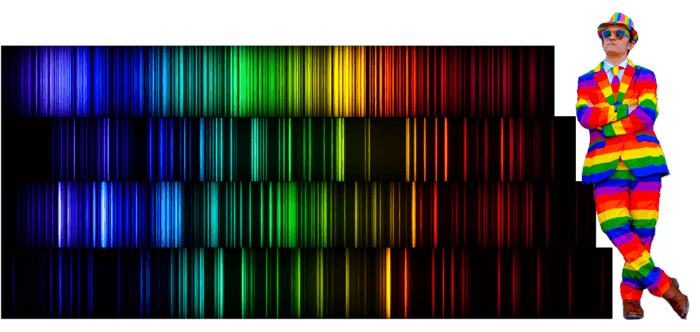

“I saw visual representations of the discrete wavelengths of light released by the elements, such as scandium,” describes W. Walker Smith, a researcher at Indiana University and the sole investigator of the work, in a media release. “They were gorgeous and complex, and I thought, ‘Wow, I really want to turn these into music, too.’”

Elements release visible light when they are energized. The light contains multiple wavelengths of color unique to each element. Wavelengths on paper can be hard to distinguish between different elements, especially for transition metals containing thousands of individual colors. Converting light into sound frequencies could provide another way for people to know the differences between elements.

The study found different ‘octaves’ of light

Scientists have attempted to combine chemistry and music before. Past studies have assigned the brightest wavelengths to single notes played on piano keys. Smith, however, says this approach downplays the rich variety of complex wavelengths produced from elements and tries to reduce them into only a few sounds.

The goal of this project was to convert wavelengths into sound while retaining as much of their complex element spectra as possible. With the help of colleagues in the music and chemistry departments, Smith designed a computer code for real-time audio that converted each element’s light data into mixtures of notes. The discrete color wavelengths transformed into individual sine waves whose frequencies sync up with the light. Their amplitude also matched the light’s brightness levels.

Through the research, Smith noticed pattern similarities between light and sound vibrations. For example, violet has double the frequency of red. In music, one doubling of a frequency is equivalent to an octave. With this logic, visible light can be considered an “octave of light.” However, an octave of light is at a much higher frequency than what the human ear can hear. To overcome this problem, Smith toned down the sine waves’ frequencies and fitted the audio output into a range where human ears could detect differences in pitch.

Some elements really sound like music

Some elements have hundreds or thousands of frequencies, allowing the notes to create harmonies and beating patterns when mixed together.

“The result is that the simpler elements, such as hydrogen and helium, sound vaguely like musical chords, but the rest have a more complex collection of sounds,” says Smith.

Calcium sounded like the chiming of bells, while the element zinc resembled “an angelic choir singing a major chord with vibrato.” Other elements sounded like a spooky noise you would hear in horror movies.

“Some of the notes sound out of tune, but Smith has kept true to that in this translation of the elements into music,” says David Clemmer, a professor of chemistry at Indiana University who helped Smith design the computer code.

The off-key tones are known as microtones and come from frequencies between the keys of a traditional piano.

“The decisions as to what’s vital to preserve when doing data sonification are both challenging and rewarding. And Smith did a great job making such decisions from a musical standpoint,” adds Chi Wang, a professor of music at Indiana University, who also helped Smith in his study.

A ‘periodic keyboard’ could help the blind learn science

Now that Smith has figured out how to create sound from elements, he hopes to use the same technology to create a new musical instrument.

“I want to create an interactive, real-time musical periodic table, which allows both children and adults to select an element and see a display of its visible light spectrum and hear it at the same time,” says Smith.

The sound-based approach could also help with creating new ways to teach chemistry. People who are auditory learners or have visual impairments may benefit the most from this approach.

Smith presented the findings at the American Chemical Society’s Spring 2023 Meeting. The study will include a musical performance of “The Sound of Molecules” featuring audio clips of a few elements and a “composition” of larger molecules.