CORK, Ireland — The curious case of a 280-million-year-old fossil has finally been solved. Researchers say the famous prehistoric remains that scientists once thought showed the earliest evidence of soft tissue in reptiles is nothing more than paint!

Tridentinosaurus antiquus was first discovered in the Italian Alps in 1931 in a layer of fine volcanic ash estimated to be around 298-273 million years old. Scientists noted how it appeared to show exquisite preservation of soft tissues in the form of a dark body outline contrasting sharply against the surrounding rock matrix. This remarkable preservation, combined with an articulated skeleton, led T. antiquus to be considered one of the oldest and best-preserved fossil reptiles known. It was eventually classified under the Protorosauria group.

When first described in 1959 by paleontologist G. Leonardi, the slender body with a long neck and tail did appear to show genuine bones of the hind limbs. However, no bones of the forelimbs, head, or tail were positively identifiable. Leonardi relied upon the shape and proportions of the dark body outline to describe and classify T. antiquus. Though questioned by some, the alleged fossil persisted in the literature for decades as an exquisitely preserved Carboniferous reptile.

After countless centuries, fossilized soft tissue is extremely hard to find. Although this fossilized skin has been celebrated in several articles and books, no one actually studied the fossil in detail. Some issues with the fossil include what reptile group the animal belonged to and its geological history. Irish researchers set off to accomplish this task and unfortunately found that the famous fossil is mostly black paint that created a lizard-shaped animal on the rock surface.

“Fossil soft tissues are rare, but when found in a fossil they can reveal important biological information, for instance, the external coloration, internal anatomy, and physiology,” says Valentina Rossi, a postdoctoral researcher in paleobiology at University College Cork and lead author of the study, in a media release. “The answer to all our questions was right in front of us, we had to study this fossil specimen in details to reveal its secrets—even those that perhaps we did not want to know.”

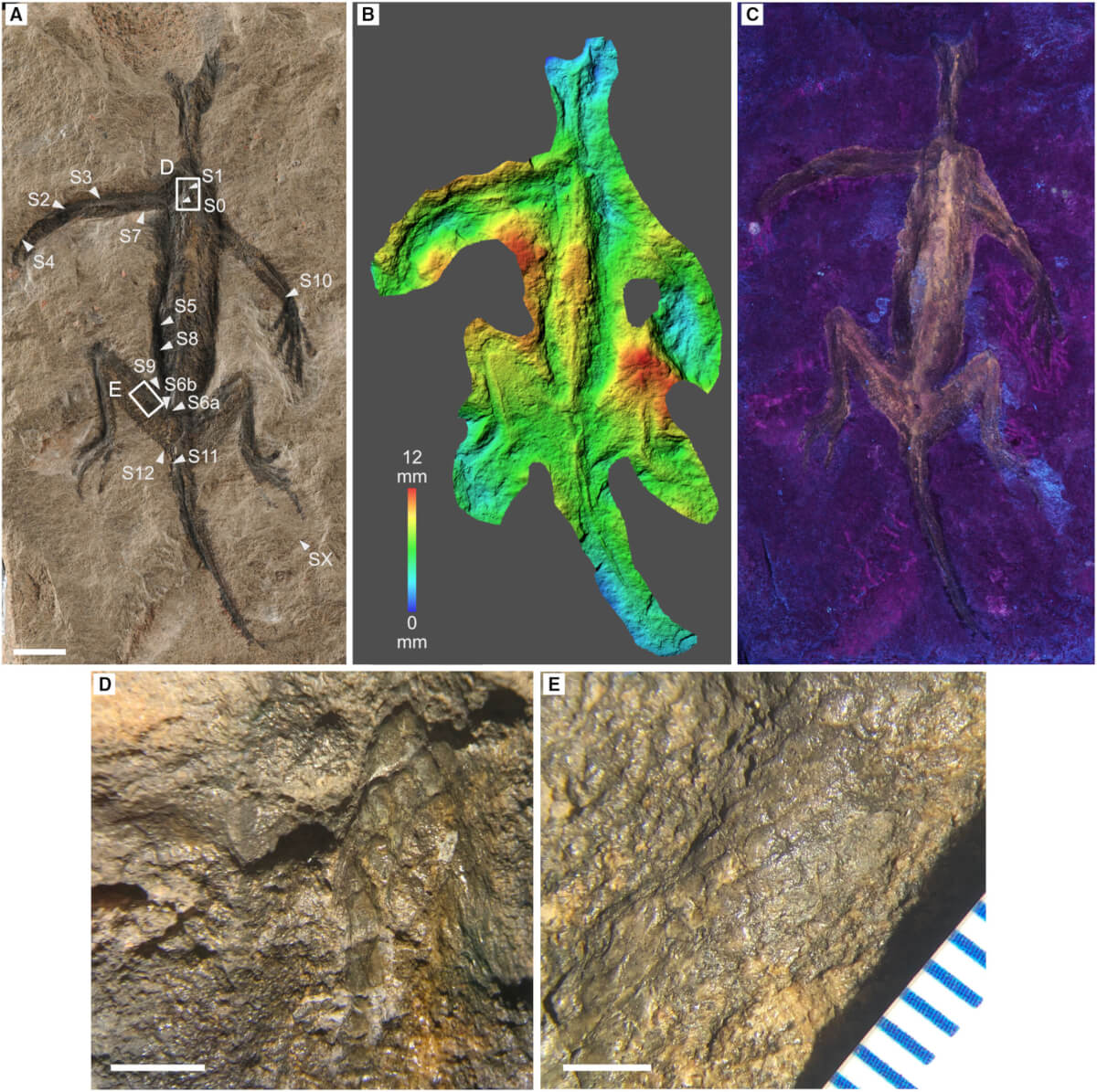

The new study utilized an array of analytical techniques – UV light photography, electron microscopy, x-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and FTIR spectroscopy – to conclusively determine that the body outline long believed to represent preserved skin and other soft tissues is actually a fake. The researchers found that the dark material fluoresces under UV, which fossilized organic tissues do not. Moreover, microscope analysis revealed a surface texture and mineral composition inconsistent with preserved soft tissues seen in other exceptional fossils. Instead, the granular texture and carbon-rich chemistry point to a manufactured pigment rather than fossilized biomolecules.

Comparison of spectroscopic data to extant reptile skin, fossilized melanin, and a sample of commercial carbon-based paint confirmed that the body outline was created with a pigment paint meant to mimic an exceptional preservation. This finding calls into question much of the original paleontological description of T. antiquus. The evidence suggests the outline of the lizard-shaped reptile was artificially created, likely with the purpose of looking like a fossil.

It’s possible past scientists could have coated the fossil with varnishes or lacquers, an old practice used to preserve fossils in museum cabinets and exhibits. The researchers still hope that underneath the coating layer are actual soft tissues in good condition for further study.

“The peculiar preservation of Tridentinosaurus had puzzled experts for decades. Now, it all makes sense. What it was described as carbonized skin, is just paint,” explains Evelyn Kustatscher, a co-author of the study.

Interestingly, the team’s examination reveals that the fossil was not a complete fake. The bone fragments of the hind limbs appear real, but poorly preserved. A further examination also showed tiny bony scales called osteoderms — similar to the scales on a crocodile — on the back of the animal. However, the fossil also shows something else beyond the black paint — a lesson to rigorously check the evidence before jumping to conclusions.

This is not the first incidence of fossil forgery being uncovered by modern analytical techniques. As early paleontological specimens can lack detailed provenance and documentation, reanalysis offers an important line of defense against intentional and unintentional misinterpretations entering the scientific literature. The exposure of T. antiquus as a fake fossil reptile serves as another reminder that compelling and perplexing fossils may require a careful reinvestigation before their status as paleontological gems is secured.

The study is published in the journal Palaeontology.