LONDON — A growth hormone administered to children, banned since 1985, is now displaying a link to Alzheimer’s disease. This hormone, extracted from the pituitary glands of human corpses, is called cadaver-derived human growth hormone (c-hGH). From 1959 to 1985, researchers in the United Kingdom say doctors administered it to at least 1,848 individuals dealing with growth deficiencies.

The use of c-hGH stopped after scientists discovered that some batches were contaminated with infectious proteins — called prions. These contaminants were responsible for causing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a fatal brain condition, among some recipients. CJD typically leads to death within eight months. A variant of CJD commonly goes by the name mad cow disease.

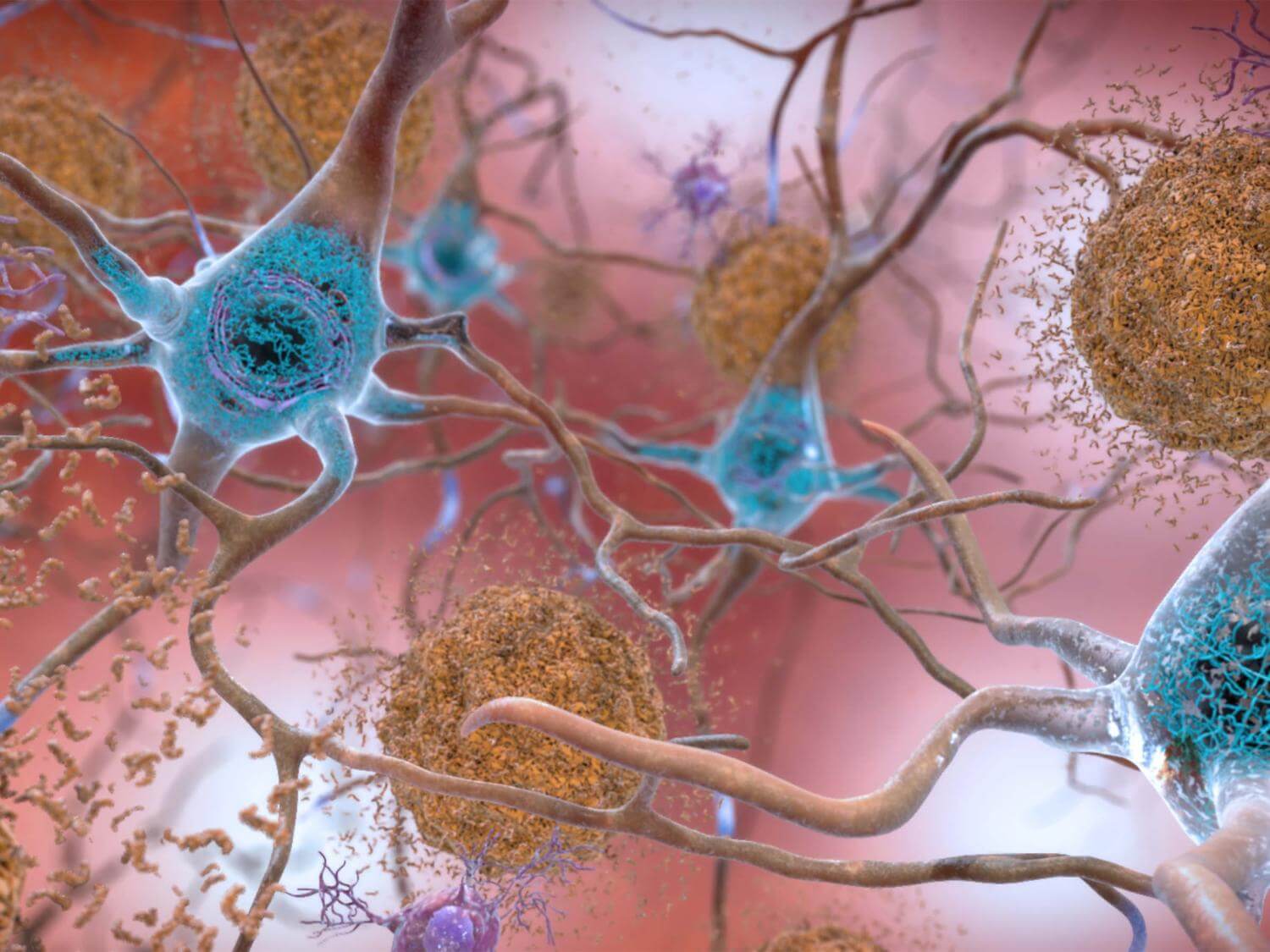

Recent findings indicate that this treatment also resulted in premature development of amyloid-beta protein deposits in the brains of participants, a known cause of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers from University College London Hospital have now demonstrated that at least five individuals who received c-hGH subsequently developed Alzheimer’s as a consequence.

-

- Dementia is a general term for a decline in memory, thinking, and reasoning abilities

- The decline in cognitive function is significant and progressive, impacting daily life

- There is currently no definitive cure that reverses these symptoms

- The number of people with dementia is projected to triple by 2050

“There is no suggestion whatsoever that Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted between individuals during activities of daily life or routine medical care. The patients we have described were given a specific and long-discontinued medical treatment which involved injecting patients with material now known to have been contaminated with disease-related proteins,” says study lead author Professor John Collinge, Director of the UCL Institute of Prion Diseases and a consultant neurologist at UCLH, in a media release.

“However, the recognition of transmission of amyloid-beta pathology in these rare situations should lead us to review measures to prevent accidental transmission via other medical or surgical procedures, in order to prevent such cases occurring in future,” Prof. Collinge continues.

“Importantly, our findings also suggest that Alzheimer’s and some other neurological conditions share similar disease processes to CJD, and this may have important implications for understanding and treating Alzheimer’s disease in the future.”

In their study, published in Nature Medicine, the researchers at University College London Hospital’s National Prion Clinic, based at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, examined eight individuals. These individuals, who all received the controversial treatment during childhood, were referred to the clinic.

The team discovered that five of these individuals exhibited symptoms of dementia. They had either already been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or met the diagnostic criteria for the condition. Additionally, another individual was identified as meeting the criteria for mild cognitive impairment. Notably, these patients were between 38 and 55 years-old when they first exhibited neurological symptoms, which is unusually young. This early onset of symptoms indicates that their condition differed from the typical sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, which is commonly associated with older age.

Furthermore, in the five patients for whom genetic testing samples were available, the researchers ruled out the possibility of inherited Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers emphasized that this situation is extremely rare. Additionally, they reassured us that since the implicated treatment is no longer in use, there is no risk of new cases arising from this cause.

“It is important to stress that the circumstances through which we believe these individuals tragically developed Alzheimer’s are highly unusual, and to reinforce that there is no risk that the disease can be spread between individuals or in routine medical care,” concludes study co-author Professor Jonathan Schott from the UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology.

“These findings do, however, provide potentially valuable insights into disease mechanisms, and pave the way for further research which we hope will further our understanding of the causes of more typical, late onset Alzheimer’s disease.” South West News Service writer Isobel Williams contributed to this report.