LANSING, Mich. — Could shoving potato chips and French fries into our mouths finally be healthy? Thanks to scientists at Michigan State University, it’s now a possibility. In a significant leap forward for snack lovers and the billion-dollar snack food industry, researchers have unveiled a discovery that could change the way we store and consume fried potatoes. This breakthrough could lead to the creation of potato products that remain tasty and healthy even when stored in cold conditions, potentially enhancing the quality of our favorite chips and fries.

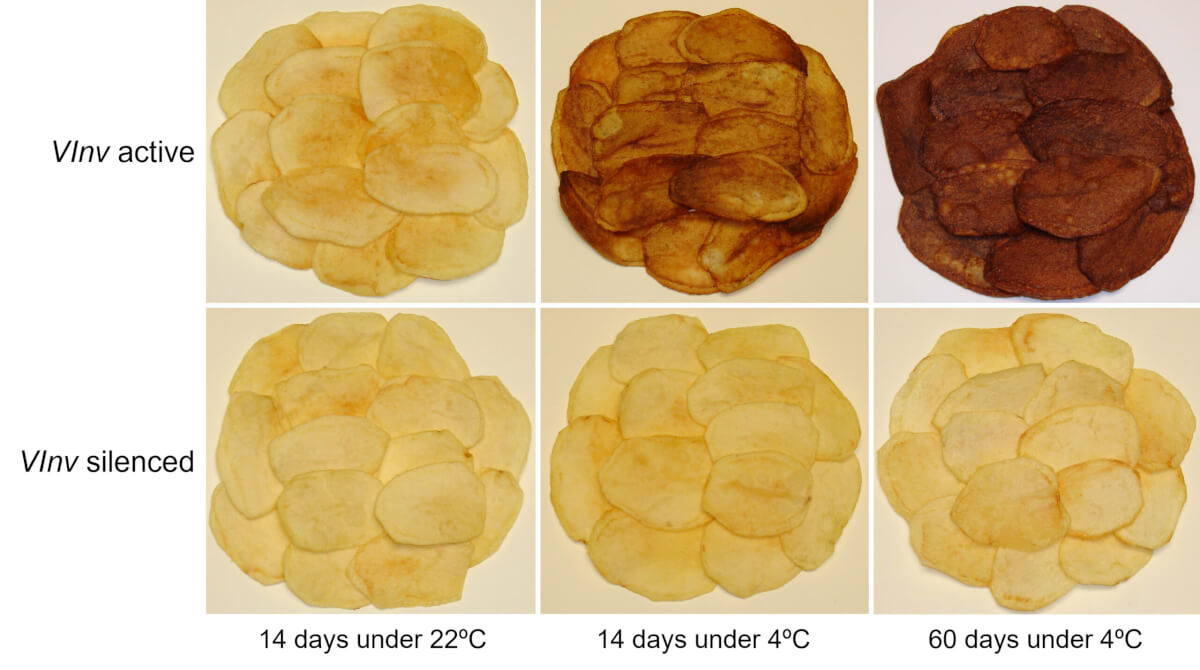

At the heart of this discovery is a process known as cold-induced sweetening (CIS), which occurs when potatoes stored at low temperatures convert their starches into sugars. This not only affects the taste by making the potatoes sweeter but also leads to the formation of acrylamide during cooking at high temperatures. Acrylamide is a compound with potential cancer risks, raising health concerns among consumers and regulators alike.

By identifying the specific gene responsible for CIS and the regulatory element that activates it in cold conditions, researchers have laid the groundwork for developing potatoes that naturally resist this sweetening process. This means that future potatoes could avoid the formation of unhealthy compounds without the need for additional, costly interventions that can alter the flavor of the final product.

“We’ve identified the specific gene responsible for CIS and, more importantly, we’ve uncovered the regulatory element that switches it on under cold temperatures,” says Jiming Jiang, an MSU Research Foundation Professor in the departments of Plant Biology and Horticulture, in a university release. “By studying how this gene turns on and off, we open up the possibility of developing potatoes that are naturally resistant to CIS and, therefore, will not produce toxic compounds.”

The journey from lab to greenhouse, and eventually to the chip bag, is one that Jiang and his team, along with collaborators across MSU’s campus and other research universities, have navigated with determination. Their comprehensive approach, which combines gene expression analysis, protein identification, and enhancer mapping, has pinpointed the regulatory element controlling the CIS gene.

“All our facilities are on campus so the research work can be done efficiently,” explains David Douches, an MSU professor who leads the university’s potato breeding program. “With our collaboration, we were able to produce a finding that paves the way for targeted genetic modification approaches to create cold-resistant potato varieties.”

The potential impact of this research extends far beyond just improving the taste and healthiness of chips and fries. By creating potatoes that can be stored in cold conditions without the negative side effects of CIS, there could be significant reductions in food waste and costs. Moreover, reducing acrylamide formation in potatoes may have broader implications for other processed starchy foods, offering a healthier alternative for consumers.

With the promise of CIS-resistant potatoes potentially hitting the market in the near future, this discovery stands as a monumental advancement in our understanding of potato development and its implications for food quality and health.

“This discovery represents a significant advancement in our understanding of potato development and its implications for food quality and health,” concludes Jiang. “It has the potential to affect every single bag of potato chips around the world.”

The study is published in the journal The Plant Cell.

You might also be interested in:

- Don’t replace potatoes: Here’s why eating starchy vegetables is so important

- Best Of The Best Potato Chips: Top 5 Mouth-Watering Crisps Most Recommended By Experts

- Best Fast-Food French Fries: Top 5 Savory Snacks To Get On-The-Go

- Immune to climate change? Geneticists are hunting for a crop-saving super potato