CHICAGO — Today, over six million Americans have a diagnosed case of Alzheimer’s. Estimates show that the number will increase to 13 million within just a few decades. Scientists estimate roughly one in every five women and one out of 10 men will eventually develop Alzheimer’s disease, an awful neurodegenerative condition resulting in the loss of memory, inability to perform everyday activities, and cognitive confusion. Now, new findings have uncovered evidence suggesting there may be an association between more visceral abdominal fat in middle age and the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

For reference, visceral fat refers specifically to fat surrounding the internal organs deep in the stomach. Study authors report that this hidden abdominal fat appears related to changes in the mind seen up to 15 years before the earliest memory loss symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease appear.

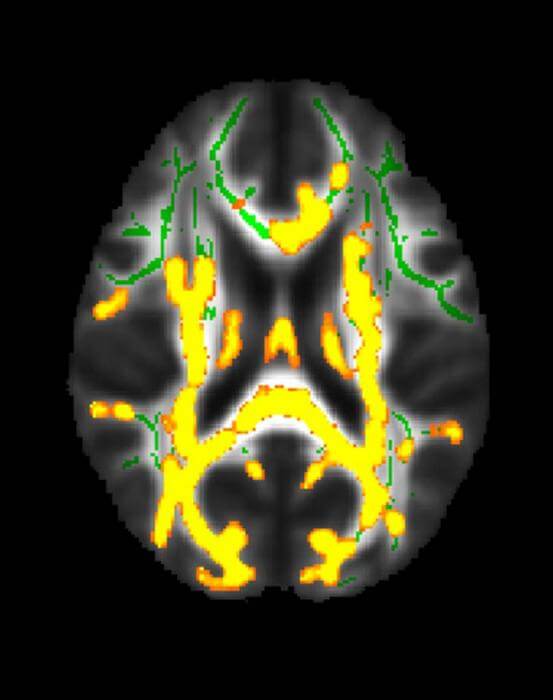

The research team assessed the association between brain MRI volumes, in addition to amyloid and tau uptake on positron emission tomography (PET) scans, with body mass index (BMI), obesity, insulin resistance, and abdominal adipose (fatty) tissue across a cognitively normal midlife population. Importantly, scientists believe both amyloid and tau proteins interfere with communications between brain cells.

“Even though there have been other studies linking BMI with brain atrophy or even a higher dementia risk, no prior study has linked a specific type of fat to the actual Alzheimer’s disease protein in cognitively normal people,” says study author Mahsa Dolatshahi, M.D., M.P.H., a postdoctoral research fellow with Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (MIR) at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in a media release. “Similar studies have not investigated the differential role of visceral and subcutaneous fat, especially in terms of Alzheimer’s amyloid pathology, as early as midlife.”

To conduct this cross-sectional study, study authors analyzed a dataset encompassing 54 cognitively healthy participants between the ages of 40 and 60, with an average BMI of 32. All participants took part in glucose and insulin measurements, as well as glucose tolerance tests. Meanwhile, researchers used abdominal MRIs to measure subcutaneous fat (fat under the skin) and visceral fat levels.

Brain MRIs, on the other hand, measured the cortical thickness of brain regions known to be affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Finally, the team used PET to analyze disease pathology across another subset of 32 participants, with a particular focus placed on amyloid plaques and tau tangles that accumulate in Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers discovered a higher visceral to subcutaneous fat ratio displayed an association with more amyloid PET tracer uptake in the precuneus cortex, a region known to be influenced early by amyloid pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Notably, this observed relationship appeared worse in men than in women. The study also reports higher visceral fat measurements are related to an increased burden of inflammation in the brain.

“Several pathways are suggested to play a role,” Dr. Dolatshahi adds. “Inflammatory secretions of visceral fat—as opposed to potentially protective effects of subcutaneous fat—may lead to inflammation in the brain, one of the main mechanisms contributing to Alzheimer’s disease.”

Senior author Cyrus A. Raji, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of radiology and neurology, and director of neuromagnetic resonance imaging at MIR, notes these results hold several key implications for earlier dementia diagnosis and intervention.

“This study highlights a key mechanism by which hidden fat can increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” he comments. “It shows that such brain changes occur as early as age 50, on average—up to 15 years before the earliest memory loss symptoms of Alzheimer’s occur.”

Dr. Raji adds these findings may point to visceral fat as a treatment target for modifying the risk of future brain inflammation and dementia.

“By moving beyond body mass index in better characterizing the anatomical distribution of body fat on MRI, we now have a uniquely better understanding of why this factor may increase risk for Alzheimer’s disease,” he concludes.

The research is set to be presented at the 109th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America.

You might also be interested in:

- People with fatty muscles are more vulnerable to declining brain health

- This common fungus can trigger ‘key player’ in Alzheimer’s disease development

- Obesity linked to significant risk of developing brain diseases

This article underscores the growing concern of Alzheimer’s disease and its potential link to visceral abdominal fat in middle age. The findings suggest that understanding the role of specific types of fat, especially visceral fat, may provide valuable insights into Alzheimer’s disease development.

For individuals grappling with Alzheimer’s, tools like Goodbyememo become especially significant. Given the progressive nature of the disease, where memory loss and cognitive confusion are inevitable, Goodbyememo offers a platform for individuals to compose heartfelt messages and share memories with their loved ones while they can. This becomes an invaluable means for those affected by Alzheimer’s to leave a lasting positive impact and ensure that their sentiments are communicated during a time when they can still actively engage in the process.

As the study emphasizes the importance of earlier dementia diagnosis and intervention, Goodbyememo aligns with the proactive approach by allowing individuals to document their thoughts, values, and experiences before the full impact of the disease sets in. In this context, Goodbyememo serves not only as a tool for personal expression but also as a way to contribute to the understanding and connection with loved ones, fostering a sense of continuity despite the challenges posed by Alzheimer’s.