SEATTLE — Humans may share over 90 percent of their DNA with their primate cousins, but researchers from the University of Washington say certain nerve cell circuits for seeing color are uniquely human. In fact, study authors say their findings indicate humans are capable of perceiving a greater range of blue tones than monkeys can.

Researchers compared connections between the color-transmitting nerve cells found in the retinas of humans with cells found in two types of monkeys, the Old World macaque and the New World common marmoset. Modern humans’ ancestors diverged from these two species about 25 million years ago.

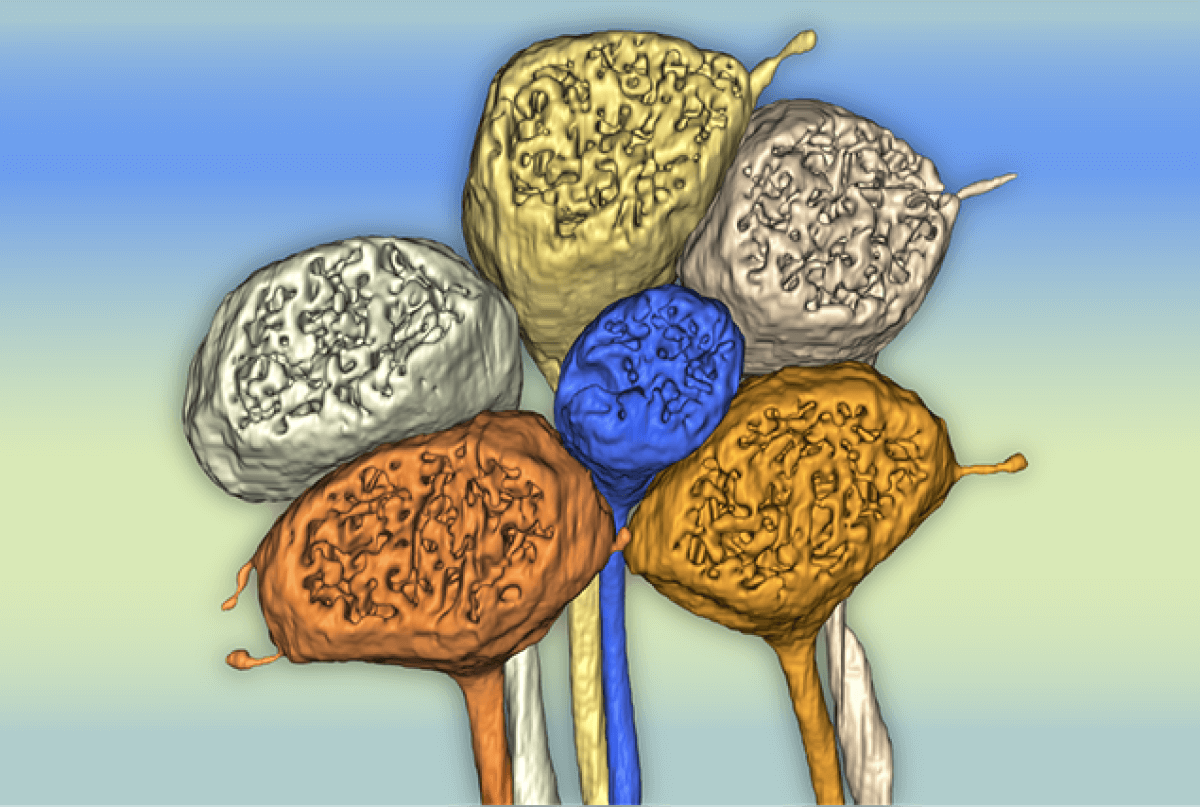

Using a fine scale microscopic reconstruction method, study authors set out to see if the neural wiring of the areas associated with color vision remained consistent across all three species, despite each taking a separate evolutionary path.

More specifically, the research team assessed the lightwave-detecting cone cells of the fovea of the retina. That small dimple is densely packed with cone cells, and considered the part of the retina responsible for the sharp visual acuity necessary to perceive key details like words on a page or what’s ahead while driving, as well as color vision.

Yeon Jin Kim, acting instructor, and Dennis M. Dacey, professor, both in the Department of Biological Structure at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, led this international, collaborative study. They collaborated with Orin S. Packer of the Dacey lab; Andreas Pollreisz at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria; as well as Paul R. Martin, professor of experimental ophthalmology, and Ulrike Grünert, associate professor of ophthalmology and visual science, both at the University of Sydney, Australia, and the Save Sight Institute.

Cone cells come in three distinct sensitivities: short, medium, and long wavelengths. Color information comes from neural circuits processing information across all three different cone types.

Study authors discovered that a specific short-wave or blue sensitive cone circuit is totally unique to humans and absent in marmosets. It also happens to be different from the circuit seen in the macaque monkey. Additional features the scientists found in the nerve cell connections in human color vision were unexpected, especially based on earlier non-human primate color vision models. As such, a clearer understanding of the species-specific, complex neural circuitry responsible for coding color perception could eventually help reveal the origins of color vision qualities distinct to humans.

Study authors also note the possibility that differences among mammals regarding visual circuitry may have been partially shaped by their behavioral adaptation to ecological niches. For example, marmosets live in trees while humans live on land. The capacity to identify ripe fruit among the shifting light of a forest, therefore, may have offered a selective advantage for particular color visual circuity. However, the actual effects of environment and behavior on color vision circuitry have not been established yet.

Comparative studies of neural circuits at the level of connections and signaling between nerve cells, researchers advise, may potentially help answer many other questions. More specifically, a better understanding of the underlying logic behind neural circuit design, as well as insights regarding how evolution has modified the nervous system to assist in shaping perception and behavior.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- Plotting primates: Monkeys are capable of complex thinking, making careful decisions

- Gray Matters: You May Be ‘Oblivious’ To Your Vision Losing Its Ability To See Colors

- Color of dishware can actually trick taste buds of picky eaters

So when will scientists be able to tell us what the “Mantis” sees?

They have 25 different types of “Cones” in their eyes.

I try to imagine what kind of fantastic world they live in, but cannot.

Physicists tell us that a 11 dimensional universe best fits our observations but have no concept of what dimensions 5 through 11 can be.

The four dimensions (3 plus time) are easily perceived but the rest?

Science is supposed to give us answers to our questions, but the more we learn, the more questions we ask on an everlasting, ever expanding quest.

The first tautology.

“I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing.” —

Socrates