CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — The entirety of human history certainly seems like a long story, but homo sapiens have only been walking the Earth for a few hundred thousand years. Our planet, on the other hand, is estimated to be somewhere around 4.5 billion years old. That means a whole lot happened before we arrived on the scene. Much of pre-human history is lost to the sands of time, but fossil discoveries represent one of the only ways for modern researchers to peer into the past. Now, scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have announced the exciting discovery of an unusually well-preserved fossil.

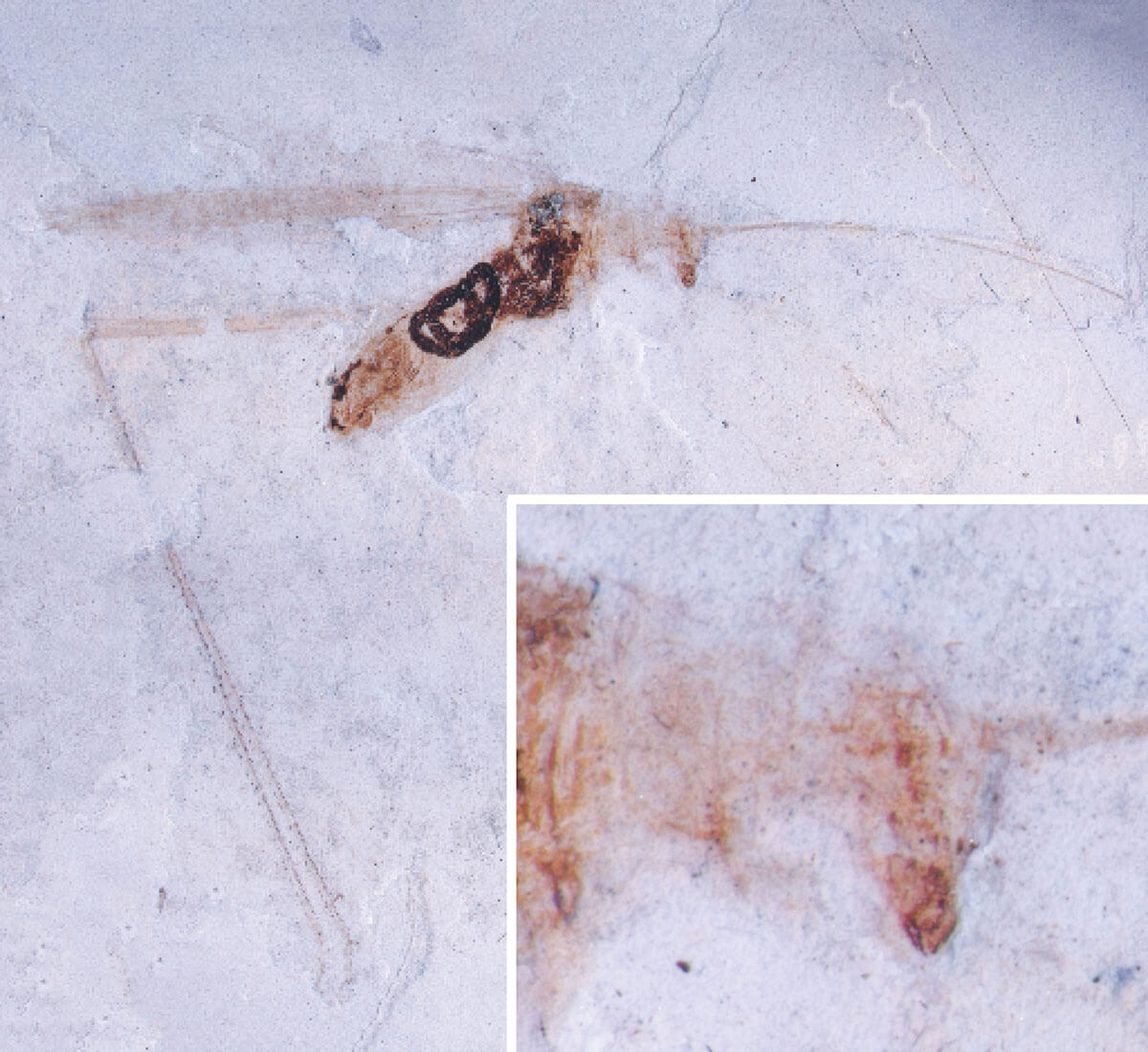

Roughly 50 million years ago, in what is today known as Northwestern Colorado, a katydid (bush cricket) died and consequently sank to the bottom of a nearby lake, quickly becoming buried in fine sediments along the way. That’s where the insect stayed for millions of years, until it was recently discovered.

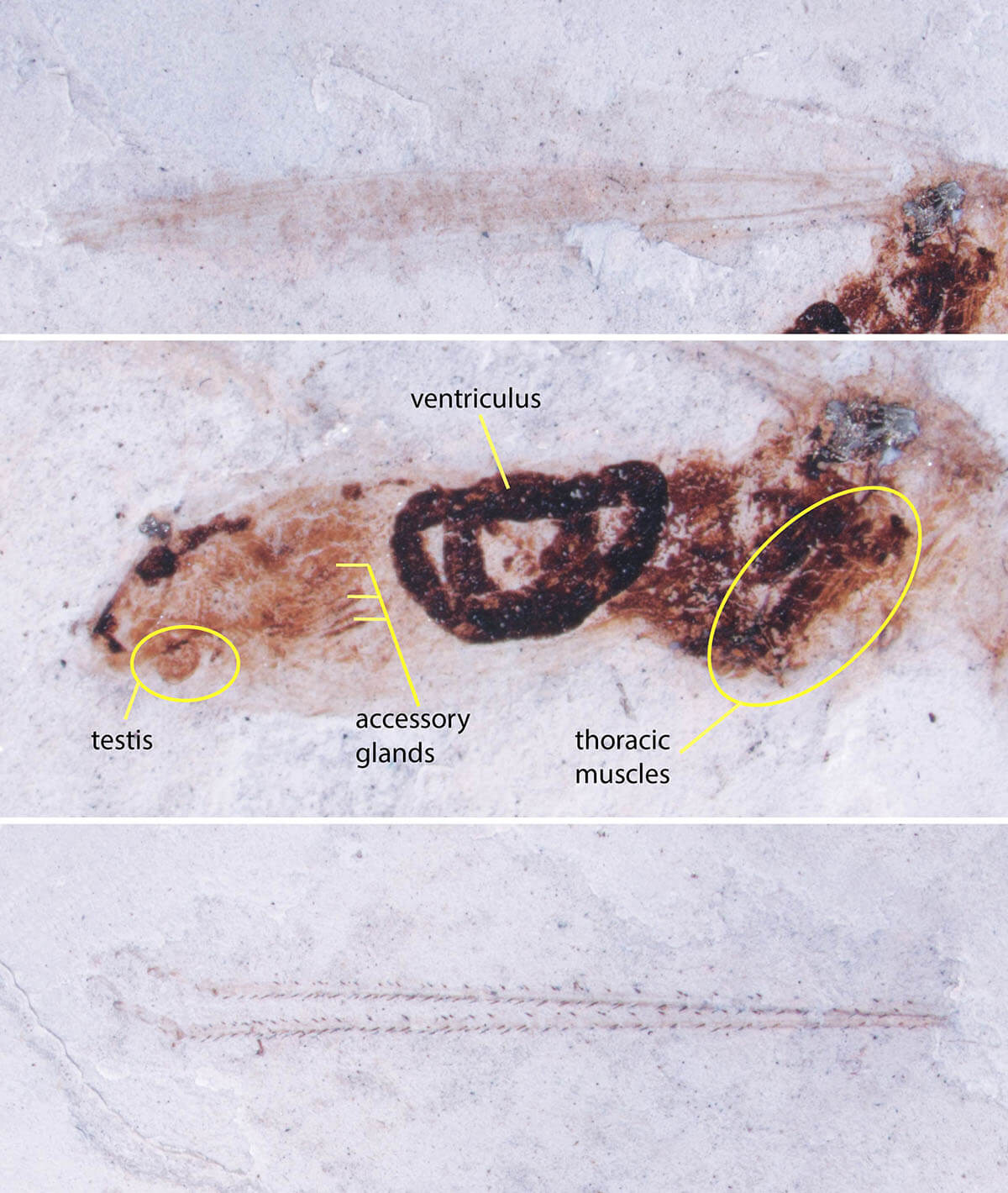

Upon placing the fossil underneath a microscope, researchers discovered that its hard structures had been preserved in the compressed shale. While that’s fairly normal for fossils of this age, several of this katydid’s internal organs and tissues were also preserved – which is incredibly rare.

“Katydids are very rare in the fossil record, so any new katydid fossil you find represents a new data point in the evolutionary history of katydids,” says palaeoentomologist and study lead Sam Heads, the director of the Prairie Research Institute’s Center for Paleontology, in a media release. “But perhaps the most striking feature of this fossil is the really exceptional, remarkable preservation of internal organs – organs that you just don’t see in fossils.”

The katydid fossil was discovered in the Green River Formation in Rio Blanco County, Colorado. That formation is vast, and actually extends into three states. It is also a famous fossil bed in the western U.S. because its fine-grained shales yield a very detailed record of the plants and animals that once inhabited the region long ago, study authors explain.

This particular katydid belongs to the genus Arethaea, a group known in modern times as thread-legged katydids due to their extremely slender, grass-like legs. This exciting fossil specimen represents a new, yet ironically extinct species. Heads and his colleagues have named the species Arethaea solterae after their colleague Leellen Solter.

Leellen Solter is a retired insect pathologist and research affiliate of the Illinois Natural History at the Prairie Research Institute. She dedicated her scientific career and expertise to the ongoing task of cataloging and organizing the vast fossil insect collection at the Center for Paleontology.

“Obviously, having a fossil species of a modern genus is really significant because it confirms the antiquity of this lineage,” Heads explains. “Now we know that about 50 million years ago, this genus had already evolved and already had a morphology that mimics the grass in which it lives and hides from predators.”

This discovery will help scientists better understand how this variety of insect evolved, as well as when they developed their trademark physical structure. Heads adds that this rare glimpse of soft internal organs in a 50-million-year-old fossil is quite astounding.

“Part of the digestive tract is preserved, a part of the midgut we call the ventriculus,” he notes. “That’s not so unusual; we have other specimens from this location that have gut traces, so I wasn’t particularly struck by that.”

However, when the specimen was examined under a microscope, researchers observed clear evidence of other internal structures they had not expected to be preserved. For example, traces of the fibers making up thoracic muscles associated with the wings or flank muscles were still intact, and there was some undifferentiated tissue known as a “fat body,” or an organ that helps with insect metabolism.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, “there are these little tubules that all seem to connect to a round structure – and that can only be a testis and accessory glands that are associated with the testis,” Heads continues. “That’s just phenomenal. I was not expecting to see that kind of structure preserved in a rock compression. I’ve never seen that before.”

To double-check this analysis, Heads and his team dissected several additional katydid specimens of the same genus in order to match up with what was being seen in the fossil.

“They look exactly the same,” he concludes. “The testis, the accessory glands and the ventriculus were all the same in the present-day katydids. I was just blown away by it. To my knowledge, this is the first example of this level of preservation.”

The study is published in Palaeoentomology.