BOULDER, Colo. — Remnants of an ancient virus may be responsible for the fatal neurodegenerative disease ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) — also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Thousands of people are diagnosed with the disease each year. Although there are currently no effective treatments, researchers at CU Boulder have made a surprising discovery that could lead to new therapies. They have identified a protein called PEG10, typically associated with placental development, as a potential contributor to ALS.

High levels of PEG10 in nerve tissue can change cell behavior in ways that contribute to the disease. The research is still in its early stages, but it offers hope for developing new treatments that target the root cause of ALS.

“Our work suggests that when this strange protein known as PEG10 is present at high levels in nerve tissue, it changes cell behavior in ways that contribute to ALS,” says senior author Alexandra Whiteley, an assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry, in a university release.

The study highlights the presence of ancient virus-like proteins in the human genome, which comprise about half of our DNA. PEG10 is one of these proteins, and while it plays a crucial role in enabling mammals to develop placentas, it can also fuel disease when present in excessive amounts. These bits of DNA left behind by viruses infected our primate ancestors 30 to 50 million years ago.

Previous studies have linked PEG10 to other conditions like certain cancers and Angelman’s syndrome. This research is the first to establish a connection between PEG10 and ALS, showing that it accumulates in high levels in the spinal cord tissue of ALS patients and interferes with brain and nerve cell communication.

Whiteley explains that PEG10 accumulation is a hallmark of ALS. She has obtained a patent for PEG10 as a biomarker for diagnosing the disease. The research began by investigating how cells eliminate excess protein, a process linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Whiteley’s lab focuses on a group of genes called ubiquilins, which help prevent protein buildup in cells. Through their research, they discovered the connection between PEG10 and ALS.

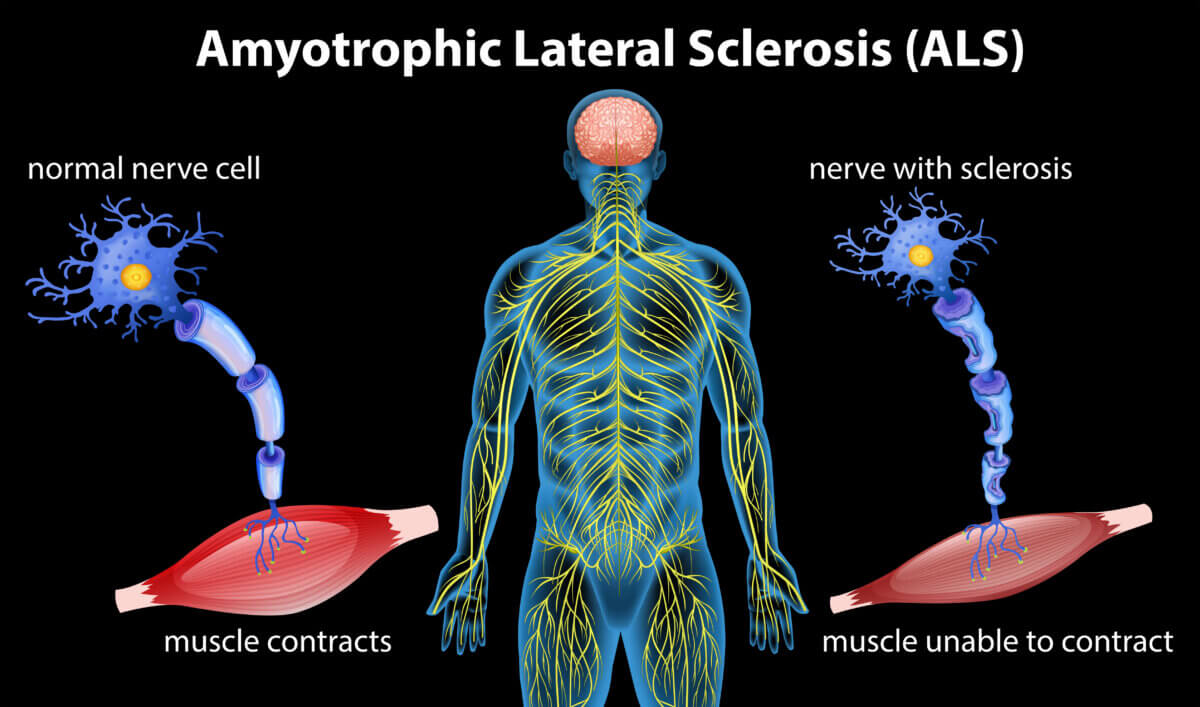

By studying animal models and analyzing spinal tissue from ALS patients, the researchers found that PEG10 overexpression disrupts the development of axons, which carry electrical signals from the brain to the body. The protein was overexpressed in both sporadic and familial ALS cases, suggesting its involvement in the disease. This finding offers new possibilities for targeting PEG10 as a treatment for ALS.

“The fact that PEG10 is likely contributing to this disease means we may have a new target for treating ALS,” Whitely says. “For a terrible disease in which there are no effective therapeutics that lengthen lifespan more than a couple of months, that could be huge.”

The research not only provides hope for ALS treatment but also deepens our understanding of protein accumulation-related diseases and the influence of ancient viruses on human health. Whiteley notes that domesticated viruses, like PEG10, can play a role in neurodegenerative diseases, despite their evolution into less harmful forms. This study serves as a reminder that what is beneficial for one part of the body, such as the placenta, may have detrimental effects on other tissues.

While further research is necessary to comprehend the molecular pathways involved and develop potential therapeutics fully, this study represents a significant step forward in ALS research. It sheds light on the role of PEG10 in the disease and opens up new possibilities for treatment and understanding the impact of ancient viral proteins on human health.

The study is published in the journal eLife.