LAWRENCE, Kan. — Imagine a time about 30 million years ago, when North America experienced dramatic cooling and drying, becoming less hospitable for primates. In this ancient setting, a mysterious loner primate named Ekgmowechashala eked out an existence on the American Plains, defying the odds. Today, paleontologists from the University of Kansas and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing have unveiled new evidence shedding light on Ekgmowechashala’s enigmatic story, thanks to fossil teeth and jaws discovered in both Nebraska and China.

To understand this discovery, we need to unravel the complex story of Ekgmowechashala and its origins.

“This project focuses on a very distinctive fossil primate known to paleontologists since the 1960s,” says study lead author Kathleen Rust, a doctoral candidate in paleontology at KU’s Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, in a university release.

“Due to its unique morphology and its representation only by dental remains, its place on the mammalian evolutionary tree has been a subject of contention and debate. There’s been a prevailing consensus leaning towards its classification as a primate. But the timing and appearance of this primate in the North American fossil record are quite unusual. It appears suddenly in the fossil record of the Great Plains more than 4 million years after the extinction of all other North American primates, which occurred around 34 million years ago.”

This unusual timing puzzled scientists and led to questions about the primate’s origins.

In the 1990s, study co-author Chris Beard, KU Foundation Distinguished Professor and senior curator of vertebrate paleontology, collected fossils in China that closely resembled Ekgmowechashala. These fossils were discovered in the Baise Basin in Guangxi, China, and marked the first step in uncovering the primate’s true story.

“When we were working there, we had absolutely no idea that we would find an animal that was closely related to this bizarre primate from North America, but literally as soon as I picked up the jaw and saw it, I thought, ‘Wow, this is it,’” explains Beard.

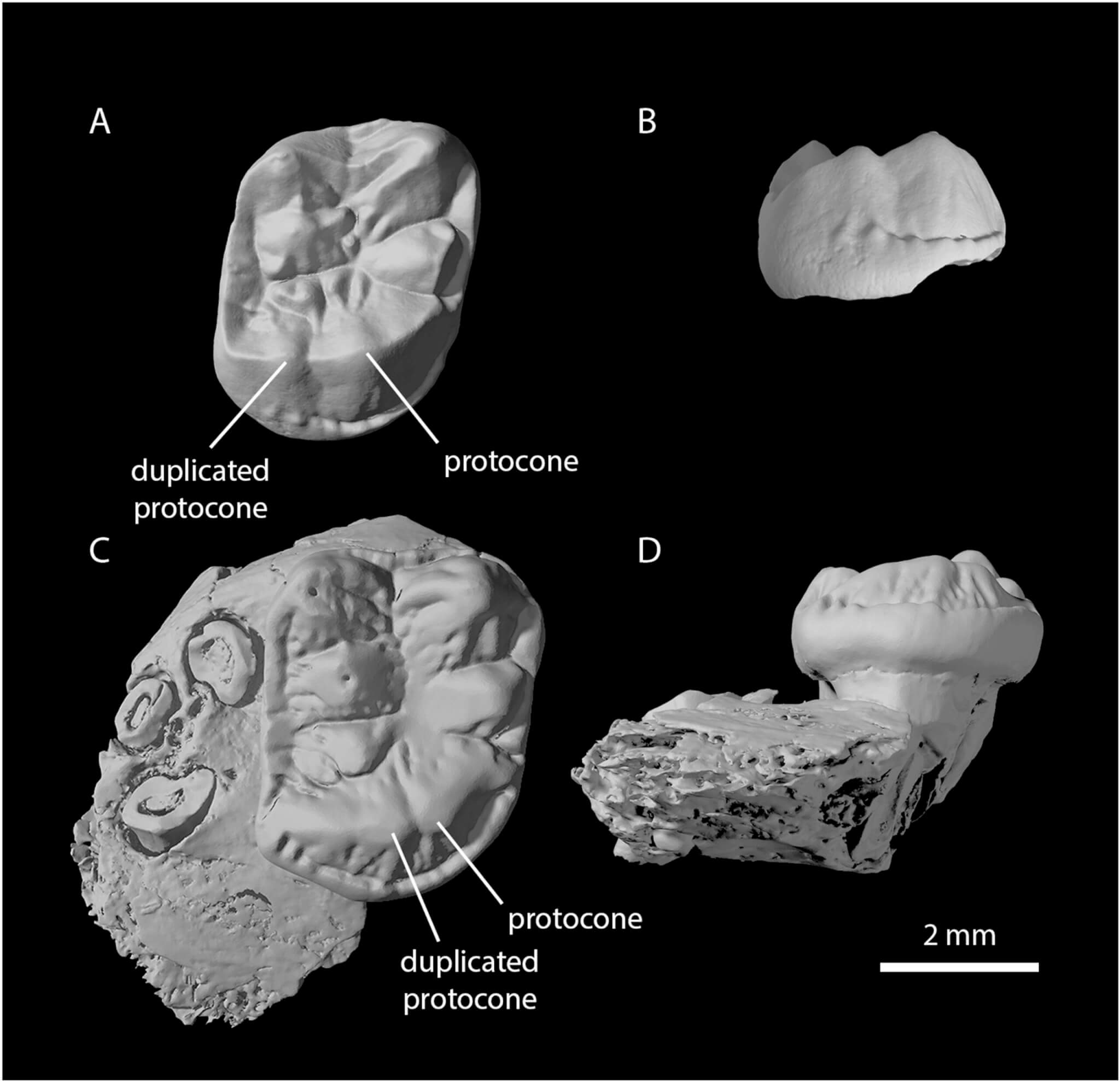

“It’s not like it took a long time, and we had to undertake all kinds of detailed analysis — we knew what it was. Here in KU’s collection, we have some critical fossils, including what is still by far the best upper molar of Ekgmowechashala known from North America. That upper molar is so distinctive and looks quite similar to the one from China that we found that it kind of seals the deal.”

The research team, led by Rust, conducted a morphological analysis, revealing a close evolutionary relationship between Ekgmowechashala and its Chinese cousin, Palaeohodites. This connection dispelled the idea that Ekgmowechashala was a relic or survivor of earlier North American primates and instead suggested that it was an immigrant species from Asia that migrated to North America during a cooler period, possibly via the Beringian region.

Species like Ekgmowechashala, which suddenly appear in the fossil record long after their relatives have gone extinct, are referred to as “Lazarus taxa.” This finding highlights the dynamic nature of evolution and how species can reappear seemingly out of nowhere.

“It’s crucial to comprehend how past biota reacted to such shifts,” notes Rust. “In such situations, organisms typically either adapt by retreating to more hospitable regions with available resources or face extinction. Around 34 million years ago, all of the primates in North America couldn’t adapt and survive. North America lacked the necessary conditions for survival. This underscores the significance of accessible resources for our non-human primate relatives during times of drastic climatic change.”

This study not only unveils the origin of an ancient primate but also contributes to our understanding of the complex evolutionary history that led to the emergence of our own species.

“Understanding this narrative is not only humbling, but also helps us appreciate the depth and complexity of the dynamic planet we inhabit,” concludes Rust. “It allows us to grasp the intricate workings of nature, the power of evolution in giving rise to life and the influence of environmental factors.”

The study is published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

You might also be interested in:

- Plotting primates: Monkeys are capable of complex thinking, making careful decisions

- Stone Age warfare likely swept through Europe 1,000 years earlier than previously thought

- The first Americans? First humans to arrive in North America may have lived 30,000 years ago