CAMBRIDGE, United Kingdom — Although it was waged over a century before the “Great War,” or World War I (1914-1918), the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) was famously referred to as the real “first world war” by Winston Churchill. Indeed, the Seven Years’ War saw international alliances led by the two great powers of the time, Great Britain and France, clash across the Americas, Europe, West Africa, and Asia. Now, an extraordinary discovery is providing a peek into the past and what it was really like all those years ago for French sailors away at sea and their families back home.

Over 100 letters sent to French sailors by their fiancées, wives, parents, and siblings – but sadly never delivered – have been opened and studied for the first time ever since they were written between 1757 and 1758. The letters offer incredibly rare and moving insights into the loves, lives, and family quarrels of the time, spanning all corners of society, from elderly peasants to wealthy officer’s wives. The documents are also a notable new source of evidence regarding French women, laborers, and different forms of literacy.

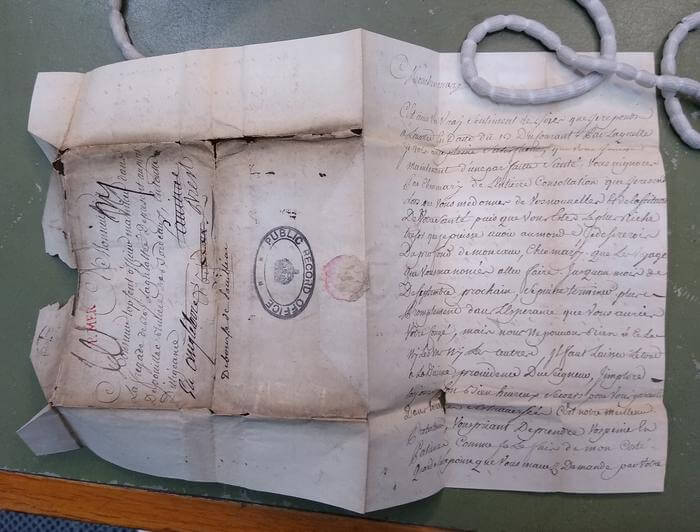

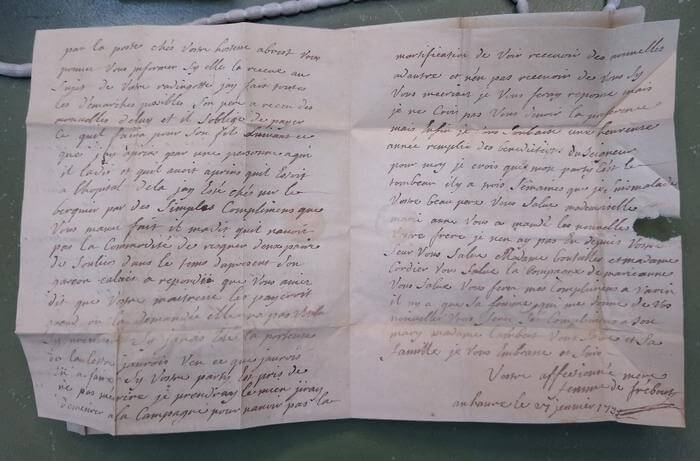

Professor Renaud Morieux, from the University of Cambridge’s History Faculty and Pembroke College, has spent months decoding the letters, often written with wild spelling, no punctuation or capitalization, and filling every inch of the expensive paper they appear on.

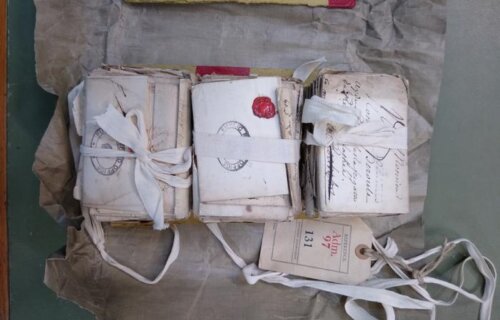

“I only ordered the box out of curiosity,” Prof. Morieux says in a university release. “There were three piles of letters held together by ribbon. The letters were very small and were sealed so I asked the archivist if they could be opened and he did. I realized I was the first person to read these very personal messages since they were written. Their intended recipients didn’t get that chance. It was very emotional.”

“These letters are about universal human experiences, they’re not unique to France or the 18th century. They reveal how we all cope with major life challenges. When we are separated from loved-ones by events beyond our control like the pandemic or wars, we have to work out how to stay in touch, how to reassure, care for people and keep the passion alive. Today we have Zoom and WhatsApp. In the 18th century, people only had letters but what they wrote about feels very familiar.”

“I could spend the night writing to you … I am your forever faithful wife. Good night, my dear friend. It is midnight. I think it is time for me to rest,” wrote Marie Dubosc to her husband, the first Lieutenant of the Galatée, a French warship, in 1758.

At the time she didn’t know where Louis Chambrelan was, or that his ship had been captured by the British. Louis would never receive that message from his beloved, and the pair would sadly never meet again. Marie passed away the following year in Le Havre, almost certainly before Louis was released. In 1761, Louis remarried back in France.

“I cannot wait to possess you,” wrote Anne Le Cerf to her husband, a non-commissioned officer on the same ship (the Galatée). Researchers explain Anne may have meant “embrace,” but she also may have been referring to making love. She signed “Your obedient wife Nanette,” which must have been an affectionate nickname. Imprisoned somewhere in England, Jean Topsent would never receive Nanette’s love letter.

During the Seven Years’ War, France commanded some of the world’s finest ships but lacked experienced sailors. Britain exploited this weakness by imprisoning as many French sailors as it could during the war. In 1758 alone, out of 60,137 French sailors, a third (19,632) were detained in Britain. During the entire span of the Seven Years’ War as a whole, there were 64,373 French sailors jailed in Britain.

Some of those sailors died from disease and malnutrition, but many others were eventually released. In the meantime, their families back home in France understandably waited and repeatedly tried to contact them and exchange news.

“These letters show people dealing with challenges collectively. Today we would find it very uncomfortable to write a letter to a fiancée knowing that mothers, sisters, uncles, neighbors would read it before it was sent, and many others would read it upon receipt. It’s hard to tell someone what you really think about them with people peering over your shoulder. There was far less of a divide between intimate and collective,” Prof. Morieux explains.

As one can imagine, back in the 18th century sending letters from France to a ship at sea was an incredibly difficult and ultimately unreliable endeavor. Many people would send multiple copies of letters to different ports hoping to reach a sailor. It was also common for relatives to ask the families of crewmates to insert messages to their loved ones in letters. Researchers found extensive evidence of such practices in the Galatée letters, which, like so many others, never reached their intended recipients.

The Galatée was sailing from Bordeaux to Quebec, but was captured in 1758 by a British ship, the Essex, and sent to Portsmouth instead. The crew was imprisoned and the ship was sold. Meanwhile, the French postal service had tried to deliver the letters to the ship, sending them to multiple ports in France. Unfortunately, the letters always arrived too late. When French authorities heard the ship had been captured, they forwarded the letters to England, where they were handed to the Admiralty in London.

“It’s agonizing how close they got,” Prof. Morieux comments.

Prof. Morieux believes British officials likely opened up and read two letters to see if they had any military value, but after deciding they only contained “family stuff,” placed the letters into storage.

The team at Cambridge has already identified every member of the Galatée’s 181-strong crew, ranging from simple sailors to carpenters and superior officers. The letters were addressed to about a quarter of the crew. Prof. Morieux has also been carrying out genealogical research on these men and their correspondents in an effort to learn more about their lives besides just what the letters revealed.

The letters detail romantic love, but more often convey family love, as well as rare insights into family tensions and quarrels at a time of war and prolonged absence. Some of the most significant letters picked out by researchers were sent to a young sailor named Nicolas Quesnel from Normandy. On Jan. 27, 1758, his 61-year-old mother, Marguerite (who was almost certainly illiterate) sent a message written by an unknown scribe to complain to her son:

“On the first day of the year [i.e. January 1st] you have written to your fiancée […]. I think more about you than you about me. […] In any case I wish you a happy new year filled with blessings of the Lord. I think I am for the tomb, I have been ill for three weeks. Give my compliments to Varin [a shipmate], it is only his wife who gives me your news.”

A few weeks later, Nicolas’ fiancée, Marianne, sent a message imploring her future husband to be a good son and stop putting her in an awkward situation. It appears Marguerite blamed Marianne for Nicolas’ silence for whatever reason. At one point, Marianne wrote: “the black cloud has gone, a letter that your mother has received from you, lightens the atmosphere.”

Then, on March 7, 1758, Marguerite wrote to her son again to complain: “In your letters you never mention your father. This hurts me greatly. Next time you write to me, please do not forget your father.”

Prof. Morieux and his team were able to uncover that, in fact, the man his mother was referring to was Nicolas’ stepfather. His biological father had died and his mother had remarried.

“Here is a son who clearly doesn’t like or acknowledge this man as his father,” Prof. Morieux notes. “But at this time, if your mother remarried, her new husband automatically became your father. Without explicitly saying it, Marguerite is reminding her son to respect this by sharing news about “your father”. These are complex but very familiar family tensions.”

Nicolas Quesnel ultimately survived his imprisonment in England, and according to researchers, eventually joined the crew of a transatlantic slave trade ship in the 1760s.

Over half (59%) of the newly opened letters were signed by women, and thus provided precious insights into female literacy, social networks, and experiences during wartime in the 18th century.

“These letters shatter the old-fashioned notion that war is all about men,” Prof. Morieux adds. “While their men were gone, women ran the household economy and took crucial economic and political decisions.”

During this period, the French navy managed its warships by forcing most men who lived near the coast to serve for one year, every three or four years. This system was predictably unpopular and many French sailors ran away once in port or applied to be released on the basis of injury.

The sister of Nicolas Godefroy, a trainee pilot, wrote: “What would bring me more pain is if you leave for the islands.” By “islands” she meant the Caribbean, where thousands of European sailors died from disease in this period. However, both Godefroy’s sister and mother refused to apply for his release from the navy. They feared that his proposed strategy could backfire and force him to stay at sea “even longer.”

All in all, study authors say Prof. Morieux’s work highlights the need for a more inclusive definition of literacy.

“You can take part in a writing culture without knowing how to write nor read,” he concludes. “Most of the people sending these letters were telling a scribe what they wanted to say, and relied on others to read their letters aloud. This was someone they knew who could write, not a professional. Staying in touch was a community effort.”

The study is published in the journal Annales Histoire Sciences Sociales.

Wonderful story! Thanks for sharing. Makes you realize people even way back then going through similar situations with emotions and feelings.