LONDON — Certain people naturally have a higher pain tolerance than others. Now, fascinating new collaborative international research reports some people who are more sensitive to pain may have long-distant Neanderthal ancestors to thank for their modern discomfort. The study, co-led by scientists at University College London, shows that three gene variants believed to be inherited by Neanderthals are associated with greater pain sensitivity in carriers today.

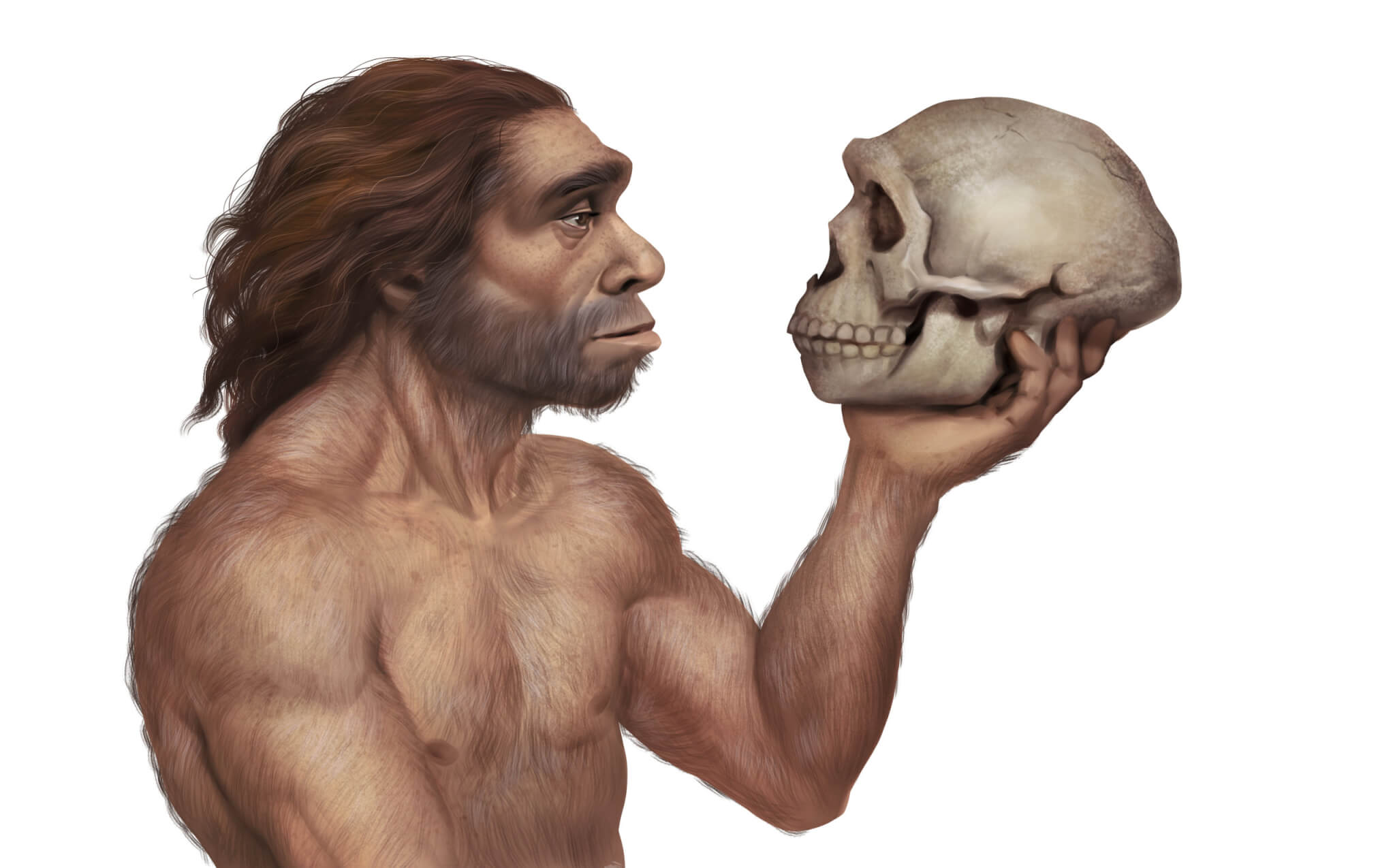

This work is just the latest to showcase how past interbreeding with Neanderthals has influenced the genetics of modern humans. The Neanderthals were a sub-species of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia roughly 100,000 years ago. Many Neanderthal fossils and artifacts have been discovered worldwide, and numerous Neanderthal genomes have successfully been reconstructed using recovered DNA.

Study authors explain individuals carrying three so-called Neanderthal variants in the gene SCN9A, which is believed to be involved with sensory neurons, tend to be more sensitive to pain from skin pricking after prior exposure to mustard oil.

Prior findings had already identified three variations in the SCN9A gene (M932L, V991L, and D1908G) in sequenced Neanderthal genomes, as well as reports of greater pain sensitivity among humans carrying all three of those variants. Still, up until this project, the specific sensory responses affected by these variants remained unclear.

Making sense of ancient genomes

This study was conducted by an international team led by researchers at UCL, Aix-Marseille University, University of Toulouse, Open University, Fudan University, and Oxford University, and part-funded by Wellcome. In all, researchers measured the pain thresholds of 1,963 people from Colombia in response to various stimuli.

The SCN9A gene works by encoding a sodium channel that is expressed at high levels in sensory neurons that detect signals emitted from damaged tissue. Researchers discovered that the D1908G variant of the gene was present in roughly 20 percent of chromosomes within this population. Importantly, around 30 percent of chromosomes carrying this variant also carried the M932L and V991L variants.

The study also discovered that the three variants were associated with a lower pain threshold in response to skin pricking after prior exposure to mustard oil, but not in response to heat or pressure. Moreover, carrying all three variants was linked with a greater pain sensitivity than carrying only one.

When the research team analyzed the genomic region including SCN9A using genetic data from 5,971 people from Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, they discovered the three Neanderthal variants tended to be more common among populations with higher proportions of Native American ancestry. For example, the Peruvian population has a 66 percent average proportion of Native American lineage.

Study authors theorize the Neanderthal variants may sensitize sensory neurons by changing the threshold at which a nerve impulse is generated. They also hypothesize such variants may be more common among populations with higher proportions of Native American ancestry due to random chance and “population bottlenecks” that took place during the initial occupation of the Americas.

While it’s known that acute pain can moderate behavior and prevent further injury, researchers say further research is warranted in order to see if carrying these variants, and subsequently having greater pain sensitivity, may have been advantageous at some point during human evolution.

Did Neanderthals have higher pain sensitivity?

On a related note, prior research by co-corresponding author Dr Kaustubh Adhikari (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment and The Open University) has discovered that humans also inherited some genetic material from Neanderthals that likely affected the shape of our noses.

“In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome was first sequenced, we have been learning more and more about what we have inherited from them as a result of interbreeding tens of thousands of years ago,” Dr. Adhikari says in a media release.

“Pain sensitivity is an important survival trait that enables us to avoid painful things that could cause us serious harm. Our findings suggest that Neanderthals may have been more sensitive to certain types of pain, but further research is needed for us to understand why that is the case, and whether these specific genetic variants were evolutionarily advantageous.”

“We have shown how variation in our genetic code can alter how we perceive pain, including genes that modern humans acquired from the Neanderthals. But genes are just one of many factors, including environment, past experience, and psychological factors, which influence pain,” adds first study author Dr. Pierre Faux of Aix-Marseille University and the University of Toulouse.

The study is published in Communications Biology.