SANTA BARBARA, Calif. — Heatwaves are now increasingly impacting the seas, resulting in what some may consider the marine equivalent of devastating wildfires, according to new research. Unlike their land-based counterparts, these dramatic periods of ocean warming can persist for months or even years, leading to mass deaths across marine life including fish, corals, kelp, algae, and seagrass. This has alarming implications for the planet.

These heatwaves are also triggering other crises such as displacement events, economic declines, and habitat loss. Even marine protected areas (MPAs) – which restrict fishing activities – are vulnerable to this phenomenon.

“MPAs in California and around the world have many benefits, such as increased fish abundance, biomass and diversity,” says Joshua Smith, who led the study while he was a postdoctoral researcher at NCEAS. “But they were never designed to buffer the impacts of climate change or marine heatwaves.”

The frequency of marine heatwaves has surged dramatically, leading to the extensive death of sea life. Humans heavily rely on the oceans for oxygen, food, storm protection, and removal of climate-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

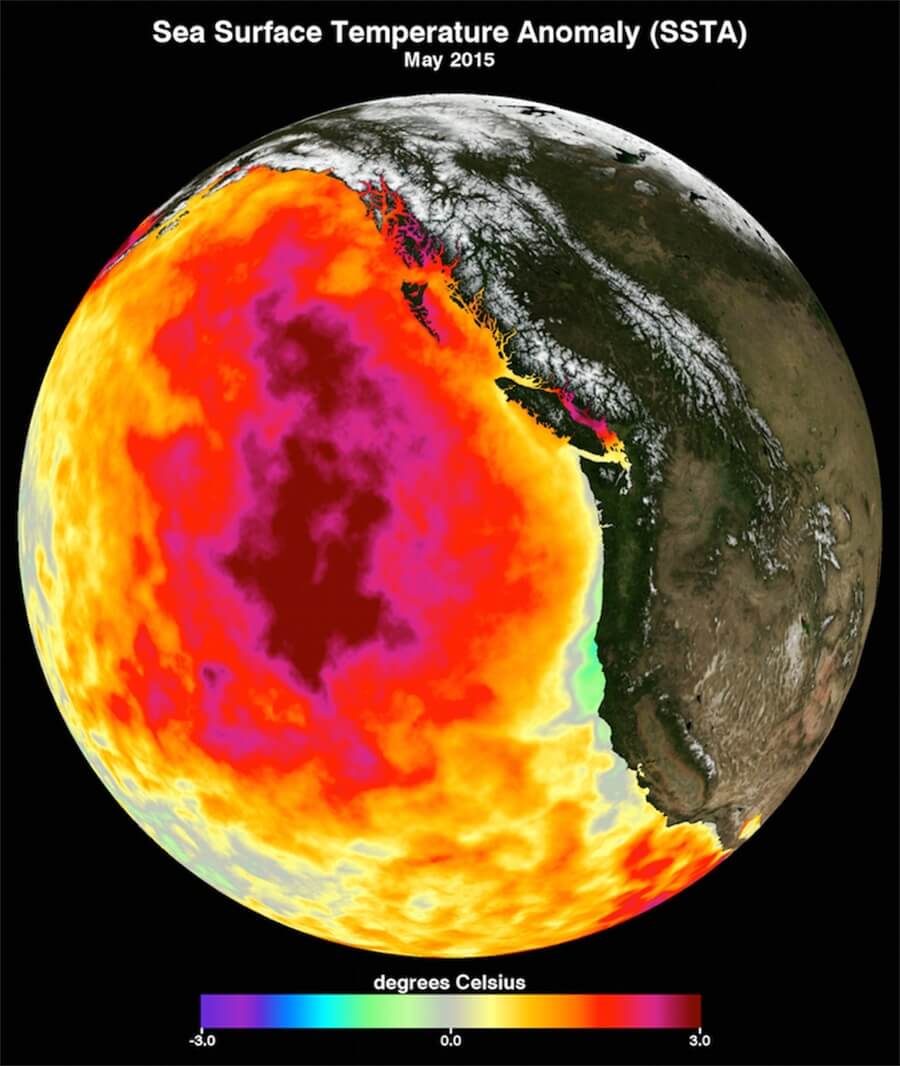

The research is based on decades of long-term ecological monitoring data gathered from diverse ocean habitats in California. It encapsulates the largest marine heatwave on record, which originated from the Pacific and moved towards California between 2014 and 2016. This exceptional heatwave, nicknamed “The Blob,” was an environmental double-whammy resulting from unusual ocean warming followed by a major El Nino event that sustained the extreme sea temperatures.

The heatwave covered the West Coast from Alaska to Baja, causing food web alteration, collapsed fisheries, and shifted marine life populations among other consequences.

The team at the University of California-Santa Barbara consolidated over a decade of data collected from 13 MPAs. These MPAs are located in a variety of ecosystems along the Central Coast, including rocky intertidal zones, kelp forests, and both shallow and deep rocky reefs. The researchers examined fish, invertebrate, and seaweed populations inside and outside these areas, utilizing data from before, during, and after the heatwave.

“We used no-take MPAs as a type of comparison to see whether the protected ecological communities fared better to the marine heatwave than places where fishing occurred,” says Smith, now an Ocean Conservation Research Fellow at Monterey Bay Aquarium, in a university release.

The results published in the journal Global Change Biology were described as “somewhat sobering” – but not entirely unexpected.

“The MPAs did not facilitate resistance or recovery across habitats or across communities,” says Jenn Caselle, a researcher with UCSB’s Marine Science Institute. “In the face of this unprecedented marine heatwave, communities did change dramatically in most habitats. But, with one exception, the changes occurred similarly both inside and outside the MPAs. The novelty of this study was that we saw similar results across many different habitats and taxonomic groups, from deepwater to shallow reefs and from fishes to algae.”

The implications are severe: every part of the ocean is under threat from climate change.

“MPAs are effective in many of the ways they were designed, but our findings suggest that MPAs alone are not sufficient to buffer the effects of climate change,” Smith says.

The ecological communities have yet to return to their former state, prior to the heatwave. A marked decline in the relative proportion of cold-water species and an increase in warm-water species has been observed. For instance, the abundance of the senorita fish, a subtropical species previously rare in central California, had a significant influence on the shift of communities. Whether these species will persist in their new locations remains uncertain.

“This study makes it clear why long-term monitoring of California’s MPAs is so critical,” Caselle explains. “Some of these time series are longer than 25 years at this point and the data are critical to understanding and readying human communities for the changes occurring in our marine communities.”

MPAs provide opportunities to study the response of marine ecosystems to changing conditions and potentially adapt management techniques accordingly.

“The ecological communities in MPAs are still being protected, even if they are different as a result of the heatwave. Given that marine heatwaves are anticipated to increase in frequency and magnitude into the future, swift climate action and nature-based solutions are needed as additional pathways to enhance the health of our oceans,” Smith states.

The frequency, duration, and severity of ocean heatwaves have intensified. The number of heatwave days increased by more than 50 percent in the 30 years leading up to 2016, compared with the period from 1925 to 1954.

“With the devastating impacts of climate change already apparent, it is very important that we are upfront about climate solutions – as long as we are burning fossil fuels and warming the globe marine ecosystems will be at risk, even if they are protected from fishing,” concludes Professor Kerry Nickols, a study co-author from Cal State University Northridge.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.

You might also be interested in:

- By 2100, climate change could destroy the ocean’s mysterious ‘twilight zone’

- 7 in 10 Americans believe climate change will have dire effects in their lifetime

- Plastic pollution may be creating a whole new ecosystem in the ocean