HANOVER, N.H. — Imagine that every time you saw someone’s face, it changed into a twisted and demonic-looking image. This may sound like a terrifying premise for a horror movie, but researchers say it’s also a very real condition. A team at Dartmouth College says that people who see demon-like faces actually have a very rare condition called prosopometamorphopsia (PMO).

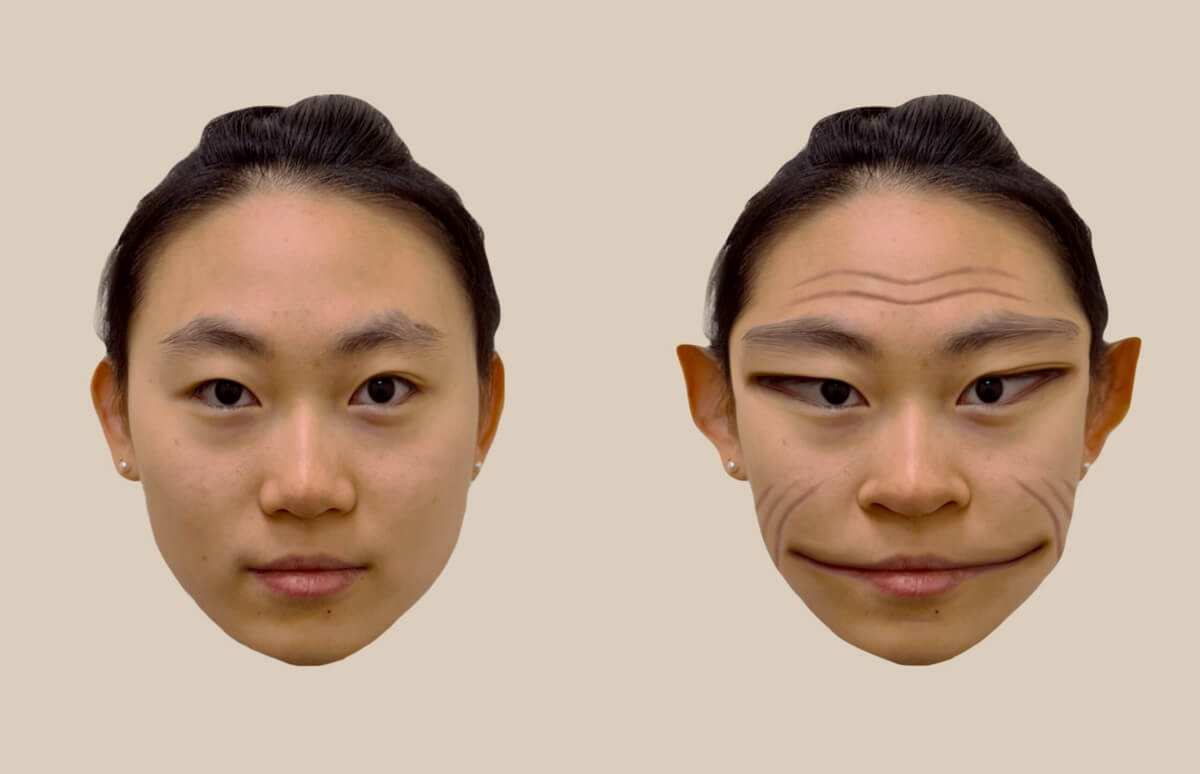

PMO causes individuals to see human faces as if they were filtered through the “Evil Smile” effect on TikTok. Researchers collaborated with a 58-year-old man afflicted with PMO, a disorder that leads to the visual distortion of faces when he’s looking directly at someone’s face. According to the findings published in The Lancet, this man perceives faces without any issues when seeing them on a screen or on paper. However, when he looks at faces in person, they appear “demonic” and distorted.

“In other studies of the condition, patients with PMO are unable to assess how accurately a visualization of their distortions represents what they see because the visualization itself also depicts a face, so the patients will perceive distortions on it too,” says lead author Antônio Mello, a PhD student in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth.

The study marks the first instance of producing accurate and photorealistic visualizations of the facial distortions experienced by an individual with prosopometamorphopsia. The term “Prosopo” is derived from “prosopon,” the Greek word for face, and “metamorphosis” denotes perceptual distortions.

Researchers have noted that PMO presents with specific symptoms that can vary from one individual to another, affecting the shape, size, color, and position of facial features, with durations ranging from days to weeks or even years.

In the study, researchers captured a photograph of a person’s face and then displayed it on a computer screen to the patient, simultaneously observing the real face of the same person. This setup allowed for real-time feedback from the patient on the differences between the on-screen face and the real one in front of him.

Using computer software, the team adjusted the photograph to align with the distortions perceived by the patient. This enabled the patient to accurately determine the similarity between his perception of the actual face and the manipulated photograph.

“Through the process, we were able to visualize the patient’s real-time perception of the face distortions,” says Mello in a media release.

In their research on additional cases of prosopometamorphopsia, the co-authors noted that some participants had consulted health professionals seeking assistance. Unfortunately, these professionals often misdiagnose them with different health conditions rather than identifying PMO.

“We’ve heard from multiple people with PMO that they have been diagnosed by psychiatrists as having schizophrenia and put on anti-psychotics, when their condition is a problem with the visual system,” says senior author Brad Duchaine, a professor of psychological and brain sciences and principal investigator of the Social Perception Lab at Dartmouth.

“And it’s not uncommon for people who have PMO to not tell others about their problem with face perception because they fear others will think the distortions are a sign of a psychiatric disorder,” Duchaine concludes. “It’s a problem that people often don’t understand.”

The Evil Smile filter has gone viral, with people attempting to eat different types of food without it being enabled.

StudyFinds’ Chris Melore contributed to this report.

Why haven’t I ever heard of this before?