WOODS HOLE, Mass. — Maybe don’t blow up Jaws next time. Swedish researchers say that shark skin may hold clues for the advancement of human medicine. Scientists from the Karolinska Institute have been investigating the potential biomedical properties of shark skin and mucus, shedding light on the remarkable healing abilities of these oceanic predators.

While sharks have long been known for their capacity to heal from wounds sustained in the wild, the scientific community is now exploring the chemical compounds present in shark skin as a source of potential medical breakthroughs.

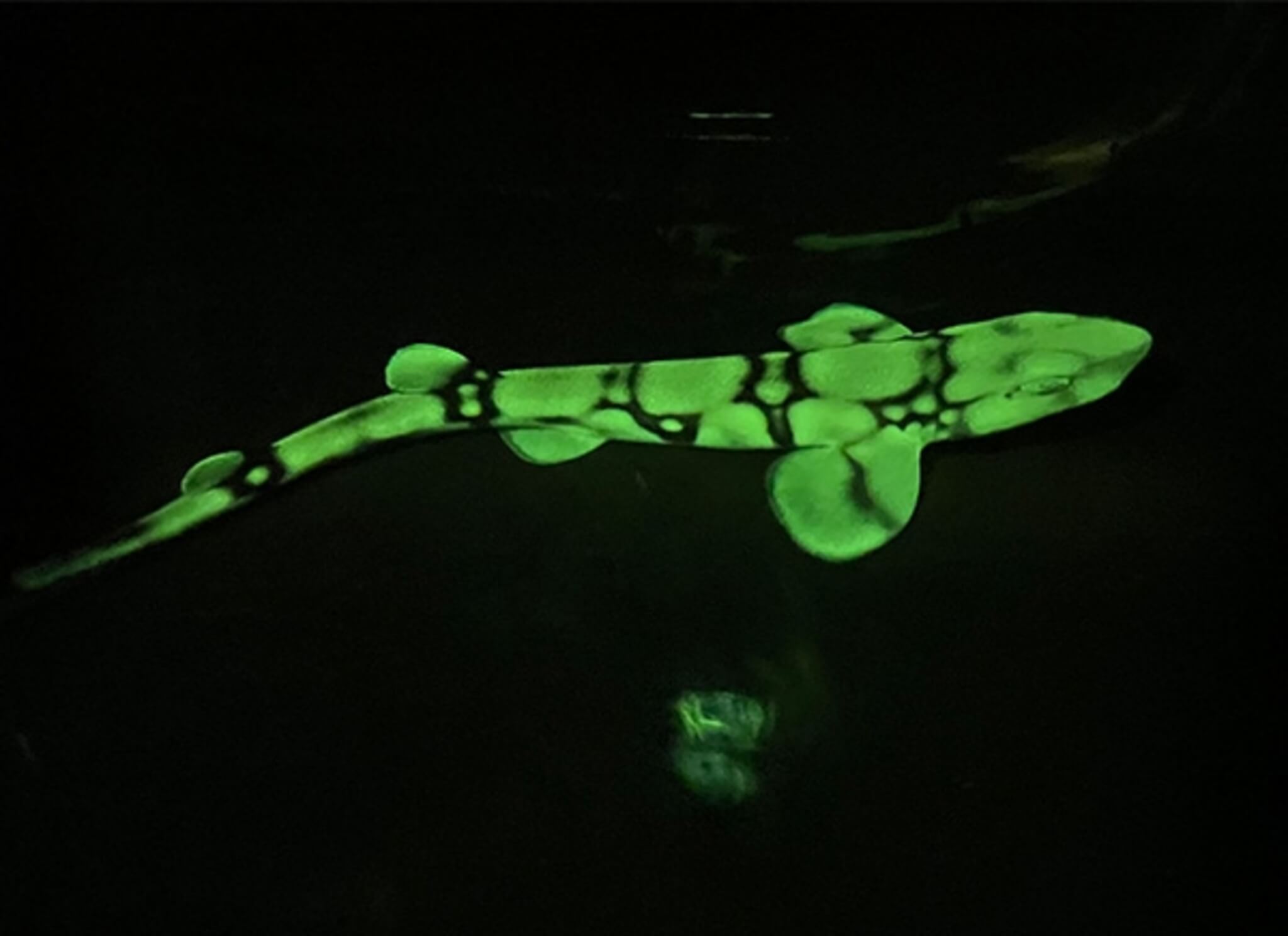

Researchers conducted a deep dive to understand the unique biochemistry of shark skin. Their research focused on the skin mucus of sharks, including the spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) and related species like little skates, conducted at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Unlike most fish species, which possess relatively smooth skin protected by a thick layer of slimy mucus, sharks have rough skin that feels like sandpaper. Initially, it wasn’t clear whether this rough skin had any protective mucus layer at all.

“Our aim in this paper was to characterize shark skin at the molecular level, which hasn’t been done in depth,” says Etty Bachar-Wikström, senior researcher at the Karolinska Institute, in a media release.

The study’s findings revealed that shark skin indeed has a very thin mucus layer, but it differs chemically from that found in bony fish. Shark mucus is less acidic and nearly neutral, bearing a closer chemical resemblance to some mammalian and even human mucus than to the mucus of bony fish.

“They’re not just another fish swimming around. They have a unique biology, and there are probably lots of human biomedical applications that one could derive from that,” explains Jakob Wikström, associate professor of dermatology and principal investigator at Karolinska. “For example, when it comes to mucin [a primary component of the mucus], one can imagine different wound care topical treatments that could be developed from that.”

Wound-treatment products have already been derived from codfish, Wikström notes, adding, “I think it’s possible that one could make something similar from sharks.”

“Besides the human relevance, it’s also important to characterize these amazing animals, and to know more about them and how they survive in their environment… I think that this is just the first step to even deeper molecular understanding,” Bachar-Wikström continues.

Researchers have more studies in progress to further characterize the distinct biochemical properties of these species, including chain catsharks (Scyliorhinus retifer), little skates (Leucoraja erinacea), and spiny dogfish.

“Animals that are far away [from us] evolutionarily can still give us very important information that is relevant for humans,” says Wikström.

While research has extensively examined the wound-healing abilities of zebrafish, sharks remain relatively unexplored in this regard.

“No one has really done it on sharks to the same extent, so it’s exciting because we really don’t know what we’re going to find,” notes Wikström. “It’s explorative research.”

The study is published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- Are shark attacks just a case of mistaken identity?

- Florida still shark attack hotspot — despite global incidents falling to 10-year lows

- ‘Holy grail’ of tracking technology may save sharks and their babies from extinction