STOCKHOLM, Sweden — Is “Jurassic Park” about to become a documentary? Researchers from Stockholm University have successfully isolated and sequenced RNA molecules from a 130-year-old Tasmanian tiger specimen. This achievement, which comes from a specimen kept at room temperature in a museum, allowed scientists to reconstruct the skin and skeletal muscle gene expression patterns of the extinct species for the first time.

The study’s implications are vast, not only for the resurrection of extinct species like the Tasmanian tiger and the woolly mammoth but also for understanding pandemic RNA viruses.

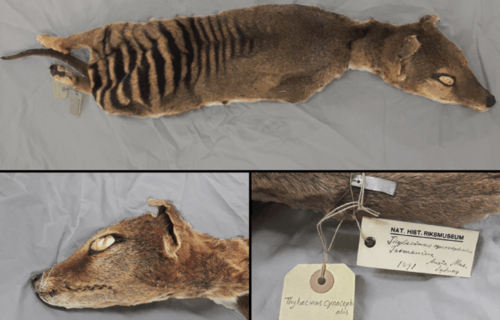

The Tasmanian tiger, also known as the thylacine, was a unique carnivorous marsupial native to the Australian continent and Tasmania. Due to human actions post-European colonization, the creature was declared a pest, leading to a bounty being placed on its head in 1888. The result was the death of the last known Tasmanian tiger in captivity by 1936.

The notion of bringing the Tasmanian tiger back to life has been a topic of significant interest. The creature’s natural habitat in Tasmania remains largely intact, and its return could restore previous ecosystem balances lost after its extinction. However, to achieve such a feat, a deep understanding of the animal’s DNA and how its genes are regulated is crucial. This information is sitting in the creature’s transcriptome (RNA).

“Resurrecting the Tasmanian tiger or the woolly mammoth is not a trivial task, and will require a deep knowledge of both the genome and transcriptome regulation of such renowned species, something that only now is starting to be revealed,” says study lead author Emilio Mármol in a university release.

By examining the Tasmanian tiger specimen from the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, the team identified gene expression patterns similar to those of living marsupial and placental mammals. The quality of the recovered data was so impressive that the researchers could identify specific proteins coded by the RNA and annotate missing genes.

“This is the first time that we have had a glimpse into the existence of thylacine-specific regulatory genes, such as microRNAs, that got extinct more than one century ago,” notes Marc Friedländer, associate professor at the Department of Molecular Biosciences, The Wenner-Gren Institute at Stockholm University and SciLifeLab.

This study sets a precedent for examining vast museum collections worldwide, offering potential insights from long-lost RNA molecules.

“In the future, we may be able to recover RNA not only from extinct animals, but also RNA virus genomes such as SARS-CoV2 and their evolutionary precursors from the skins of bats and other host organisms held in museum collections,” says Love Dalén, professor of evolutionary genomics at Stockholm University and the Center for Palaeogenetics.

The study is published in the journal Genome Research.

You might also be interested in:

- Climate change is speeding up extinction rates in the United States

- Biologists say mass extinction event is accelerating: More than 500 species could disappear by 2040

- Life of a woolly mammoth retraced thanks to 17,000-year-old fossilized tusk