OXFORD, United Kingdom — Elephants rarely get cancer, and scientists are getting to the bottom of this — literally. Researchers recently found a clue in their testicles that could reveal how elephants evolved to resist the development of cancerous tumors.

The ability to avoid cancer is called Peto’s Paradox. The theory first emerged from a famed epidemiologist named Richard Peto who made an interesting observation while out on the field. Normally, a larger animal would have more cells and chances for cell division — which would increase their cancer risk. However, Peto noticed two of the largest animals on the planet — whales and elephants — don’t develop cancer.

Their protection against cancer comes down to their genes. The TP53 gene in particular has captured scientists’ attention in recent years for the product it makes, the protein P53. This protein has the task of fixing any damaged DNA when a cell is dividing. Humans have only one copy of this all-important protein and if it misses any mistakes, they can possibly turn into mutations that turn a normal cell into a cancerous one.

Unlike humans, elephants evolved to have 20 copies of the TP53 gene. The extra oversight makes it harder for a mutation to go unnoticed, allowing elephants to roam cancer-free. So, what makes elephants so special to have been blessed in the evolutionary lottery of life?

The current study suggests elephants evolved this ultimate genetic defense against cancer as a way to shield sperm from hot temperatures normally seen in habitats they reside in, like the savannahs of Africa.

To have healthy sperm and pass your genes on to the next generation — the main purpose of life from an evolutionary point of view — the male’s testes need to maintain a cool temperature that’s several degrees lower than their normal body temperature. The scrotum is thought to have evolved as a way of providing a cool environment that would allow sperm to be stored safely with testes descended into the scrotum. Elephants lack this testicular descent.

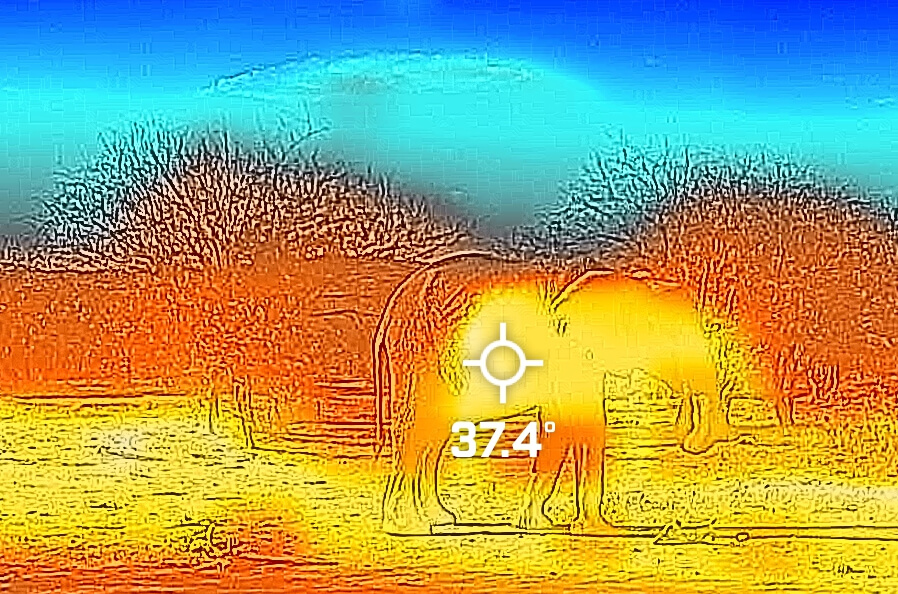

Elephant testicles are huddled close to the body which would expose them to higher temperatures from body heat. For example, their bulky figure and thick skin makes it easier to trap heat and raise body temperatures to levels where it would normally disturb mammalian metabolism and sperm production.

The study authors suggest the extra copies of the TP53 genes developed as a way to avoid overheating during sperm production. This argument is also supported by the fact that evolution is normally a slow process on somatic cells, which make up bodies, organs, and tissues. Germ cells like sperm and eggs, on the other hand, have more exposure to different mutations and provide more opportunities for evolutionary changes to take place. Fighting against cancer appears to be an unintended evolutionary side-effect, the team explains.

“Elephants provide us with a unique system to study the evolution of a robust defense mechanism against DNA damage and explore the intricate details of the p53 complex in our own battle against cancer and ailments like aging,” explains Professor Fritz Vollrath, the chairman of the elephant research group Save The Elephants and the study’s author, in a media release. “Novel insights in this field are always important, but especially now that overheating is becoming ever more of an issue also for us humans.”

The study is published in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution.

You might also be interested in:

- Elephant genes could hold the secret to preventing cancer

- Do family genes matter? Cancer is not a purely genetic disease, study finds

- Losing the male sex chromosome is fueling cancer in older men

I’m not sure about this. Elephants can sit down like toddlers and climb over fences, one leg at a time. Their internal testicles enables this flexibility. If they had external testicles they would be handicapped in the range of their movement as 6 ton of elephant would not want sit on them.

I would suggest there would be other biological methods of cooling their testicles. Whales have an artery that runs to their tail fins and then continues to the internal testicles. The blood is effectively cooled when it reaches the testicles, thus keeping them at a lower than body temperature.

so should i walk around with an ice pack on my nuts .