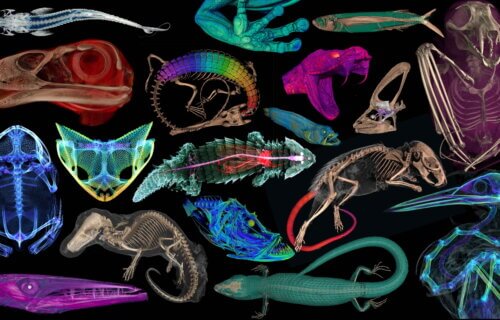

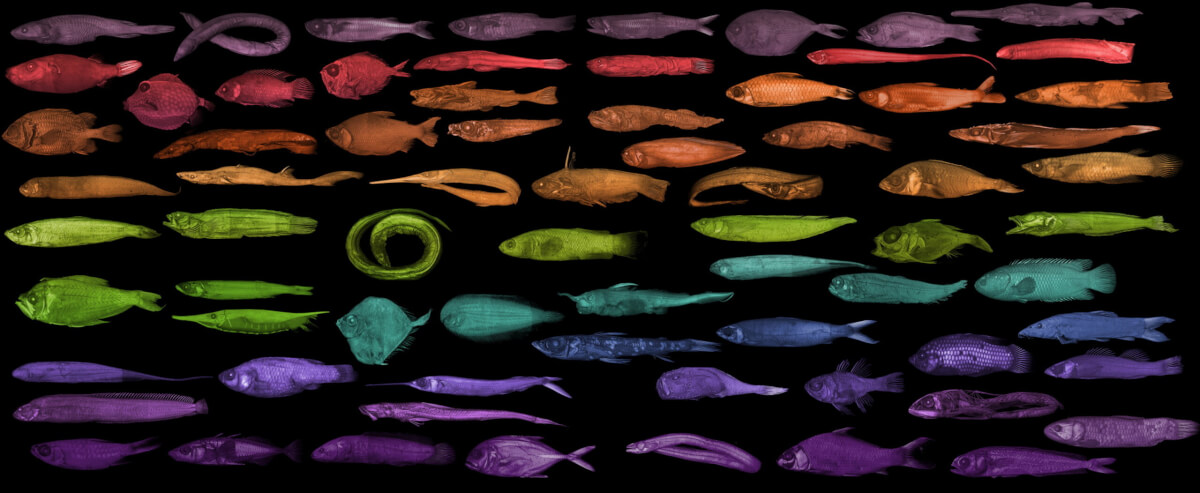

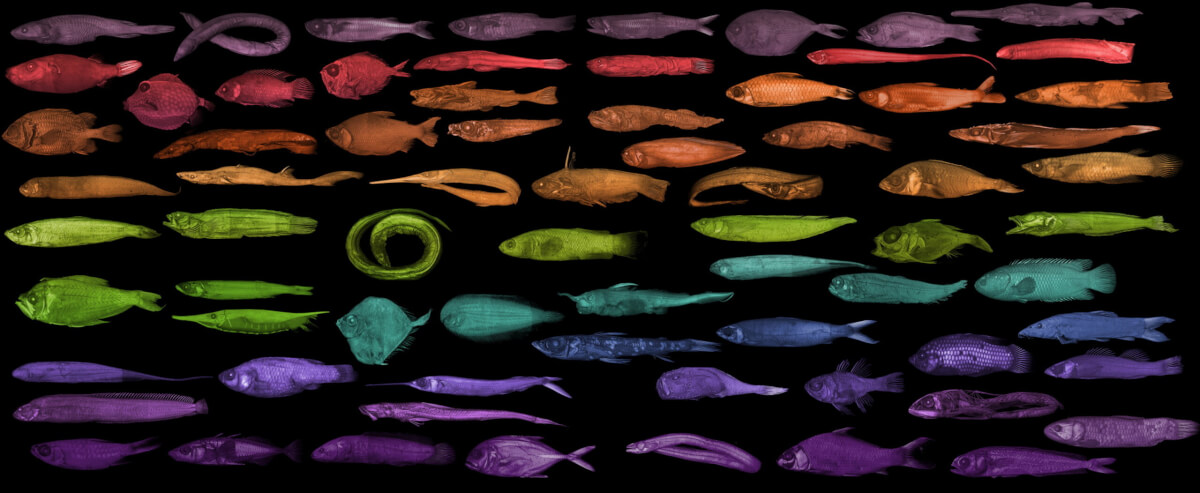

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — In an exciting leap forward for science, a revolutionary project is transforming how we see the natural history of vertebrates — animals with backbones like fish, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. This ambitious initiative, called openVertebrate (oVert), united 18 institutions over six years and digitally captured more than 13,000 specimens in stunning 3D detail. Those otherworldly images are now freely accessible online for anyone curious about the natural world.

“When people first collected these specimens, they had no idea what the future would hold for them,” says Edward Stanley, co-principal investigator of the oVert project and associate scientist at the Florida Museum of Natural History, in a media release.

Initially, the wonders of natural history were confined to the cabinets of the affluent few centuries ago. However, the vision has since expanded, with scientists aiming to share the marvels of biodiversity with the public. Despite this, the vast majority of these treasures have remained out of public view, locked away for specialized scientific research until now.

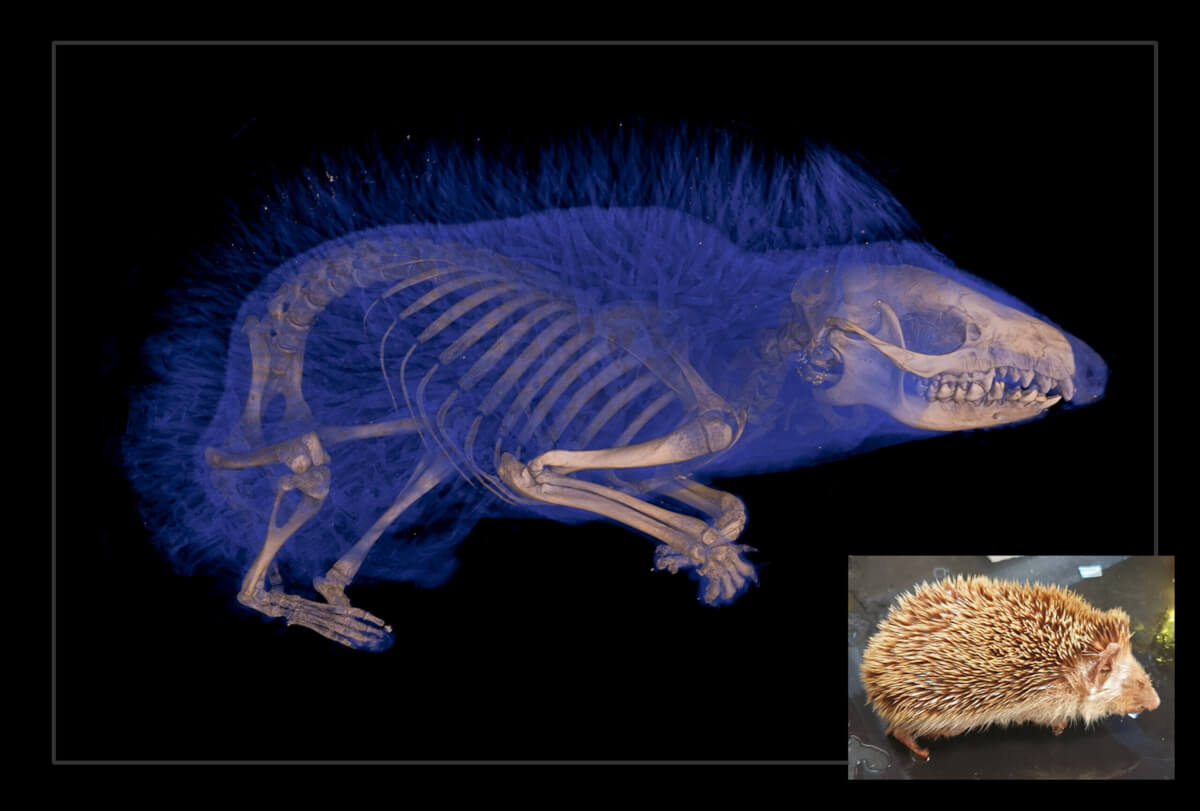

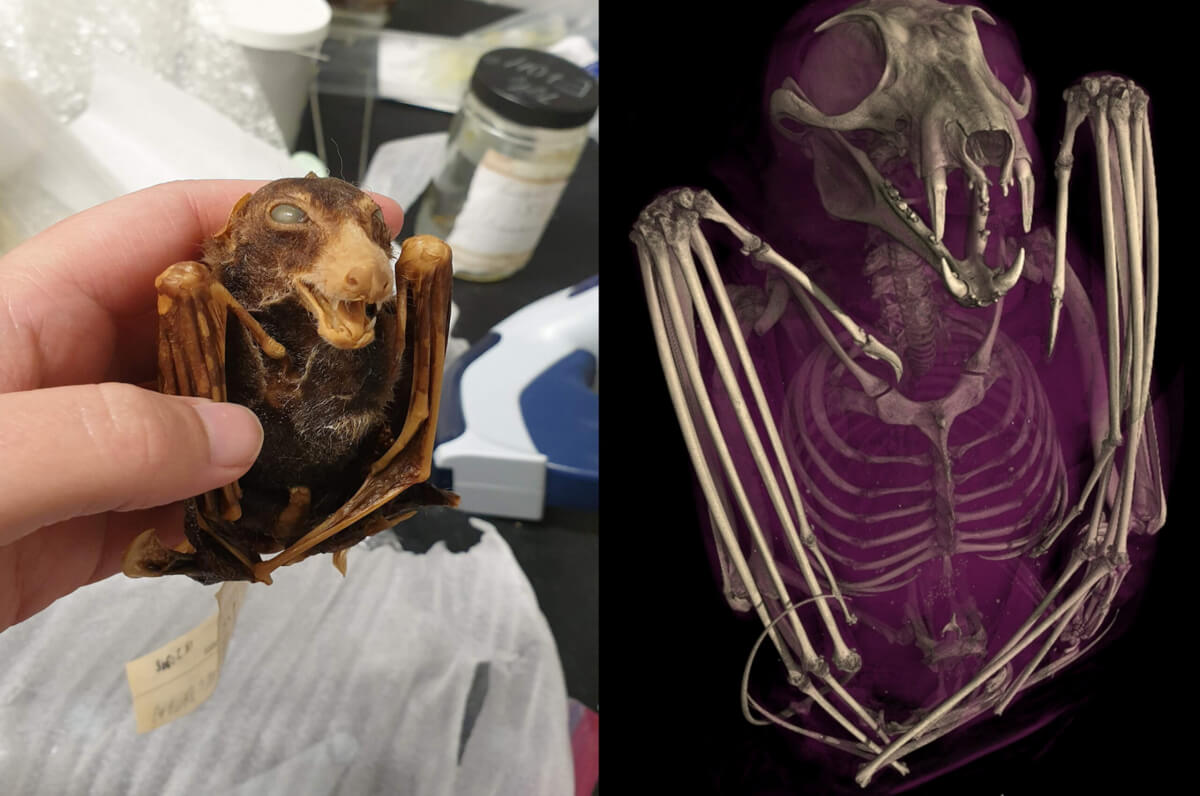

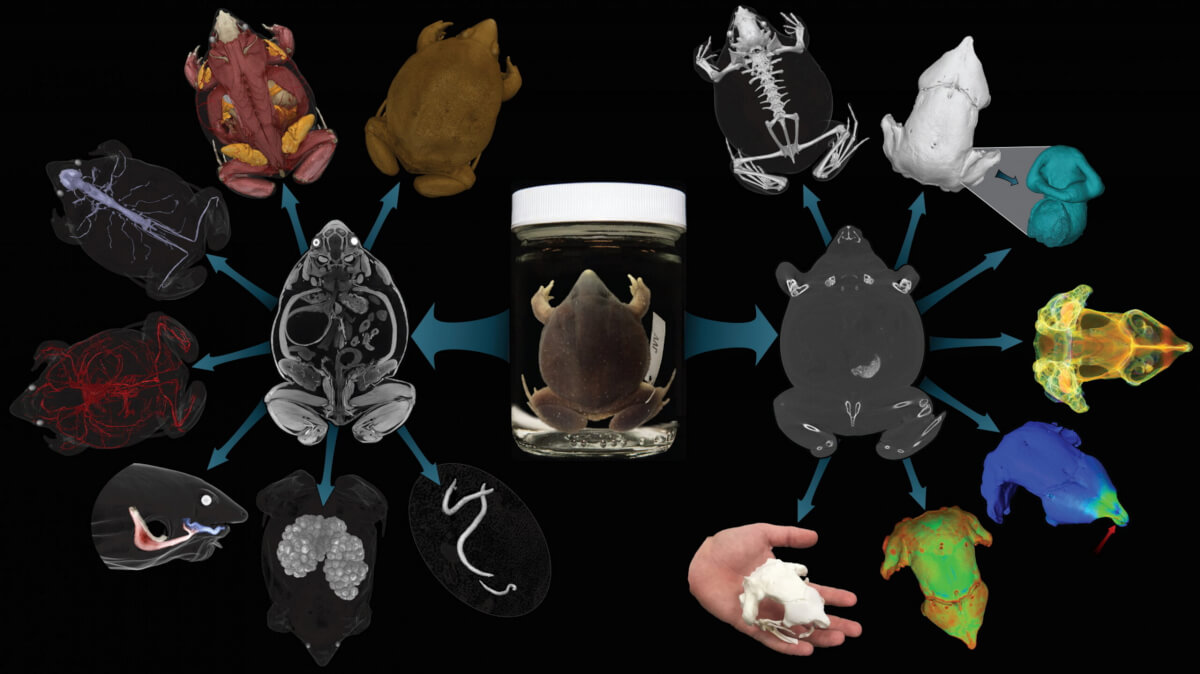

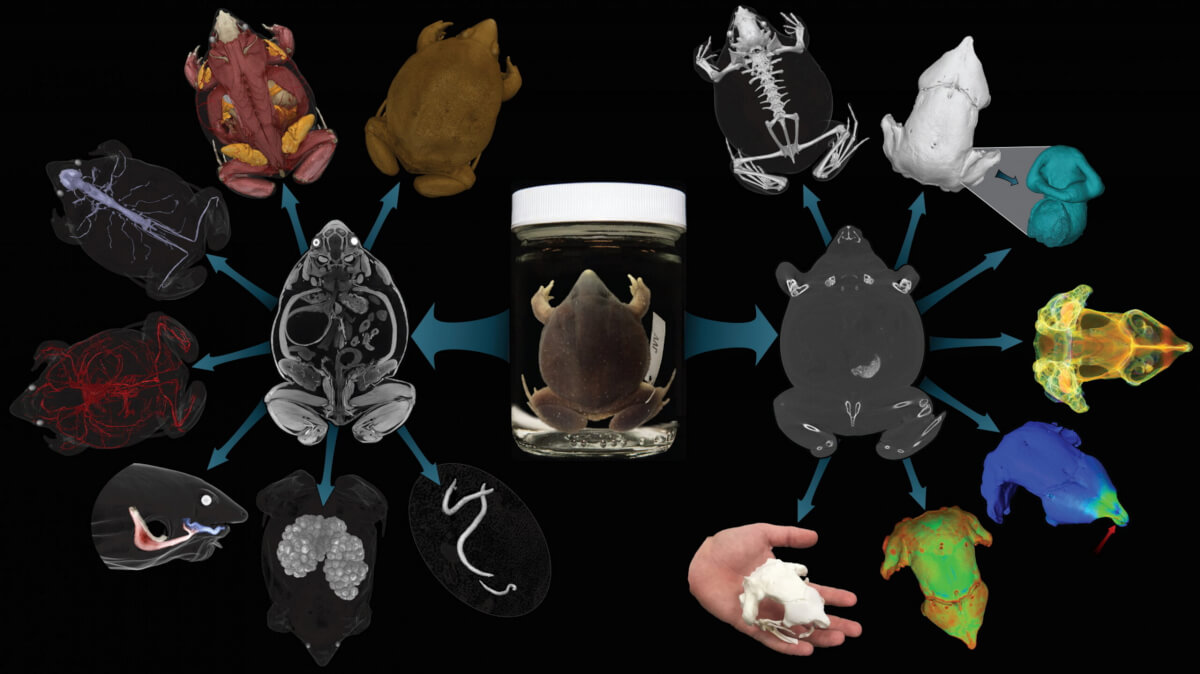

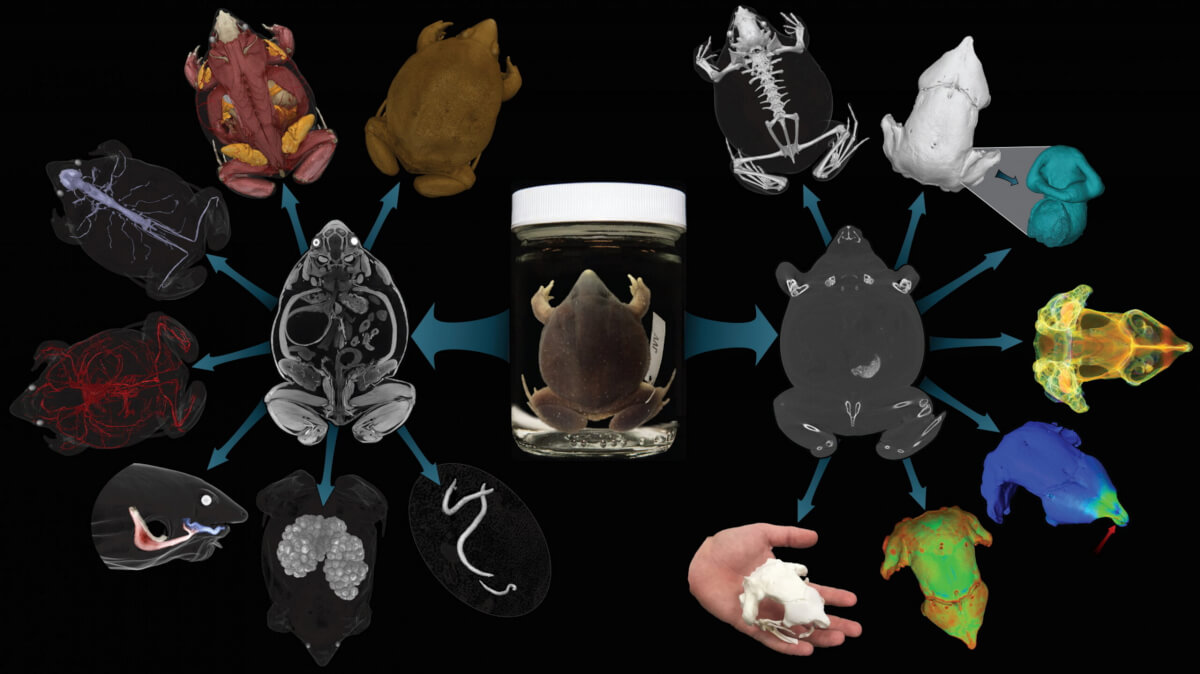

The oVert project represents a monumental shift away from dissection to examine various animals. By utilizing CT scanning technology, researchers can now peer inside the skeletons of these animals without harming the specimens. This non-invasive method even allows for the examination of soft tissues in some cases, thanks to a special staining process.

“Museums are constantly engaged in a balancing act,” explains David Blackburn, the project’s lead principal investigator. “You want to protect specimens, but you also want to have people use them. oVert is a way of reducing the wear and tear on samples while also increasing access, and it’s the next logical step in the mission of museum collections.”

The initiative has not only provided access to these specimens for scientists worldwide but has also ignited the imaginations of educators, artists, and the general public. For example, using 3D models, artists have crafted lifelike animal replicas, and educators have enriched science education, making complex concepts more tangible and engaging for students.

“It’s been a game-changer for my evolution unit,” says Jennifer Broo, a high school teacher in Cincinnati. “I teach juniors and seniors, and I absolutely love them, but they can be a tough audience. They know when things are fake, which makes them less engaged. Using the oVert models, you can teach concepts at an appropriate level while also maintaining the authenticity of the science. My class has gotten so much better because I have had the opportunities to work with and expose my students to real data.”

“Generating the data is just the start,” says Jaimi Gray, a postdoctoral associate at the Florida Museum who’s working on NoCTURN (Non-Clinical Tomography Users Research Network), a project developed toward the end of oVert to make the best use of CT scans possible. “The aim of oVert was always to facilitate the exploration of vertebrate diversity. We’re going to keep exploring, but the goal of NoCTURN is to give people the tools to use the data, whether it’s for research, education or industry.”

The project received $2.5 million in initial funding from the National Science Foundation, alongside additional grants totaling $1.1 million.

The findings are published in the journal Bioscience. To see all of the specimens scanned for the project, click here.

You might also be interested in:

The project’s reach extends beyond mere observation. It has unveiled remarkable discoveries about the animal kingdom, such as the unexpected bone structures in the tails of spiny mice and insights into the evolutionary history of frogs’ dental patterns. These findings challenge previous assumptions and open new avenues for research.

The challenge now lies in developing sophisticated tools to analyze this wealth of data.

“Generating the data is just the start,” says Jaimi Gray, a postdoctoral associate at the Florida Museum who’s working on NoCTURN (Non-Clinical Tomography Users Research Network), a project developed toward the end of oVert to make the best use of CT scans possible. “The aim of oVert was always to facilitate the exploration of vertebrate diversity. We’re going to keep exploring, but the goal of NoCTURN is to give people the tools to use the data, whether it’s for research, education or industry.”

The project received $2.5 million in initial funding from the National Science Foundation, alongside additional grants totaling $1.1 million.

The findings are published in the journal Bioscience. To see all of the specimens scanned for the project, click here.

You might also be interested in:

The project’s reach extends beyond mere observation. It has unveiled remarkable discoveries about the animal kingdom, such as the unexpected bone structures in the tails of spiny mice and insights into the evolutionary history of frogs’ dental patterns. These findings challenge previous assumptions and open new avenues for research.

The challenge now lies in developing sophisticated tools to analyze this wealth of data.

“Generating the data is just the start,” says Jaimi Gray, a postdoctoral associate at the Florida Museum who’s working on NoCTURN (Non-Clinical Tomography Users Research Network), a project developed toward the end of oVert to make the best use of CT scans possible. “The aim of oVert was always to facilitate the exploration of vertebrate diversity. We’re going to keep exploring, but the goal of NoCTURN is to give people the tools to use the data, whether it’s for research, education or industry.”

The project received $2.5 million in initial funding from the National Science Foundation, alongside additional grants totaling $1.1 million.

The findings are published in the journal Bioscience. To see all of the specimens scanned for the project, click here.

You might also be interested in: