STATE COLLEGE, Pa. — Vast regions of our planet, where over half the global population resides, may soon become uninhabitable due to extreme heat, a new study warns. Researchers at Penn State say billions in the Americas, Asia, and the Middle East might have to relocate if global temperatures keep rising because of climate change. The human body can only endure certain levels of heat and humidity before facing life-threatening health complications.

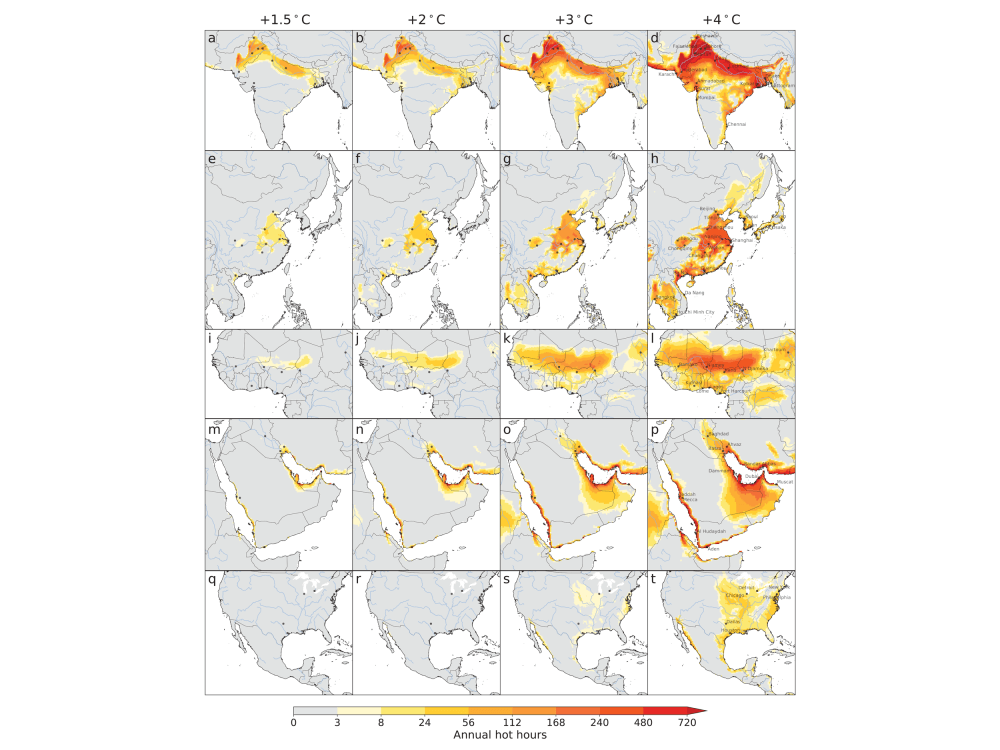

A collaborative research team determined that should temperatures exceed 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial benchmarks, many areas in lower-income countries could become uninhabitable due to severe heat. A 4.5°F increase could subject over four billion individuals in countries like India, Pakistan, eastern China, and sub-Saharan Africa to extended periods of unbearable heat.

Rises of 3.6°F could introduce intolerable heat and humidity levels in the eastern and central United States, parts of South America, and Australia. Under such conditions, affected individuals would struggle to regulate their body temperature naturally, prompting potential migrations and increased risk of mortality.

The alarming study emphasizes that emission reductions are pivotal to preventing such grim outcomes. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century, global temperatures have surged approximately 1.8°F. In 2015, 196 countries endorsed the Paris Climate Agreement, aiming to cap temperature increases at 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

As global temperatures soar, billions may surpass their physiological heat limits. The research team, from Penn State College of Health and Human Development and Purdue University, modeled projected temperature rises, ranging from the 2.7°F set by the Paris Agreement to a dire 7.2°F degree scenario.

In their work, the team identified regions where escalating temperatures would lead to untenable heat and humidity for humans.

“To understand how complex, real-world problems like climate change will affect human health, you need expertise both about the planet and the human body,” says Dr. Larry Kenney, a study co-author and a professor at Penn State, in a university release. “Collaboration is the only way to understand the complex ways that the environment will affect people’s lives and begin to develop solutions to the problems that we all must face together.”

Young, healthy individuals can tolerate a wet-bulb temperature — the lowest temperature achievable through evaporation — of roughly 87.8°F at 100 percent humidity, as determined by Penn State researchers last year. This threshold, however, is influenced by factors like physical activity, wind speed, and solar radiation.

Historically, temperatures surpassing human limits have been fleeting, mostly observed in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The team’s findings suggest that a 3.6°F rise would mean billions in regions like Pakistan, India, eastern China, and sub-Saharan Africa would annually endure long stretches of extreme heat. These areas would primarily witness high-humidity heatwaves, which hinder sweat evaporation. Moreover, many affected residents in these lower-to-middle-income countries might lack access to air conditioning, leaving them particularly vulnerable.

Should global warming surpass 5.4°F, regions from Florida to New York and Houston to Chicago would encounter conditions surpassing human endurance. South America and Australia would similarly be affected.

While the U.S. might experience more frequent heatwaves at current projections, they might not consistently surpass human limits.

“Models like these are good at predicting trends, but they do not predict specific events like the 2021 heatwave in Oregon that killed more than 700 people or London reaching 104°F last summer,” says lead author Daniel Vecellio, a bioclimatologist who completed a postdoctoral fellowship at Penn State with Kenney.

The research team has conducted extensive experiments to understand the interplay of heat, humidity, and physical exertion on human endurance. As they explain, once certain thresholds are surpassed, even though not immediately lethal, relief becomes essential to prevent ailments like heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and cardiovascular strain.

A study from 2022 showed that human tolerance limits for heat and humidity were lower than previously believed. Based on this foundation, the team projected how different global warming scenarios could influence human habitability across the world.

One crucial takeaway from the research is that humid heat poses a more significant threat than dry heat. Policymakers must reconsider current heat-mitigation strategies, and invest in measures addressing these looming challenges.

While focusing on temperature extremes, the researchers urge people to remain vigilant about severe heat and humidity, even when below the stipulated thresholds. Older adults, in particular, can experience heat stress at milder conditions.

“Heat is already the weather phenomenon that kills the most people in the United States,” adds Dr. Vecellio. “People should care for themselves and their neighbors — especially the elderly and sick — when heatwaves hit.”

For instance, many of the victims in Chicago’s 1995 heatwave were seniors who succumbed to a mix of elevated body temperatures and cardiovascular issues.

To curb global temperature increases, emissions of greenhouse gases, particularly CO2 from burning fossil fuels, must decrease. The consequences of inaction could be dire, especially for lower-income countries. The city of Al Hudaydah in Yemen offers a distressing glimpse of potential futures: with a 7.2°F rise, it would face over 300 days annually of intolerable heat, rendering it nearly uninhabitable.

“The gravest heat stress will manifest in less affluent regions with booming populations. Despite their minimal greenhouse gas emissions compared to richer nations, billions in these countries will suffer, with potential fatalities,” adds co-author Matthew Huber, professor of earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences at Purdue University. “However, affluent nations won’t be spared either. In our interwoven world, repercussions will be felt everywhere.”

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- Today’s record-breaking heatwaves will be the norm by 2050, study warns

- Global warming: Here’s where climate change could lead to record-setting heatwaves soon

- Ocean apocalypse? Heatwaves in the Pacific acting like wildfires in the sea

South West News Service writer James Gamble contributed to this report.