(© Ezume Images - stock.adobe.com)

BOSTON — Think of your immune system as an army. Its duty is to protect and defend the body from its enemies: disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens. It detects and obliterates emerging tumors and cleans up its messes made in the line of duty. This army’s mission statement: always differentiate between self and non-self, sparing self, and disabling non-self. If the army fails to make this distinction, it can mistakenly launch an assault against self – not-so-friendly fire — causing autoimmune disorders.

New research at the Harvard Medical School reveals a novel mechanism that explains how the body’s most powerful immune troops — T cells (think special forces) — learn to distinguish self and non-self.

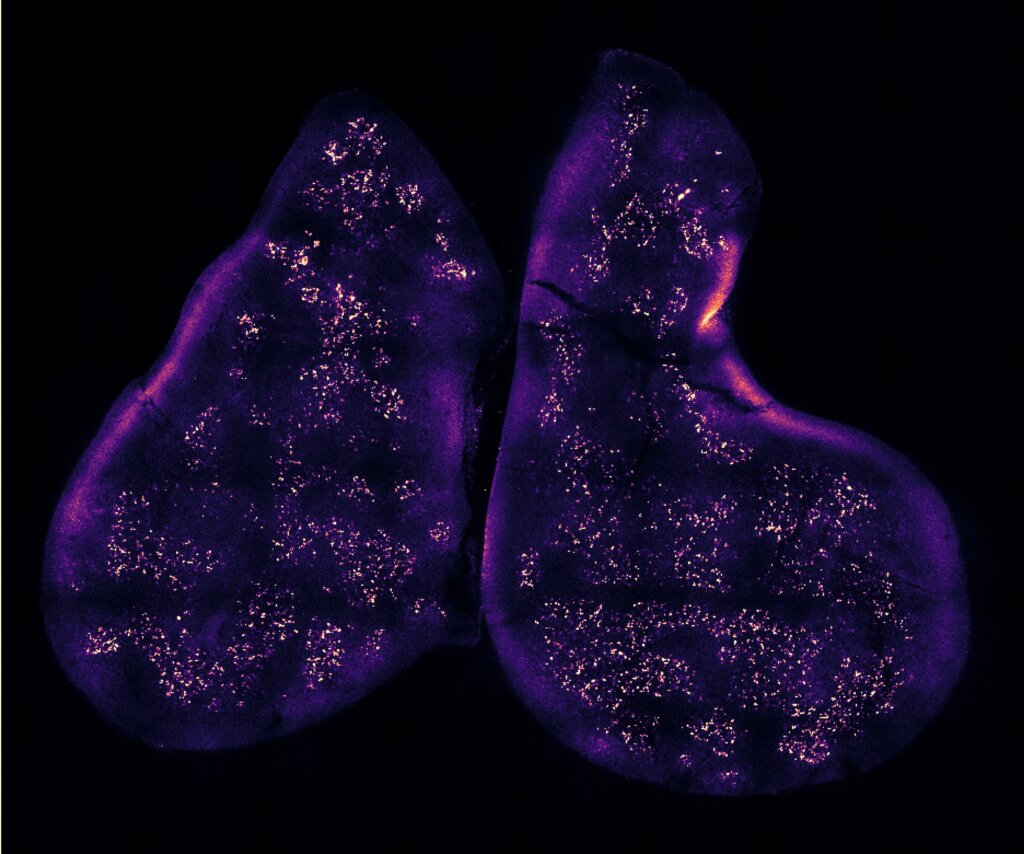

T cells recognize and eliminate pathogens and cancer cells. They form long-term memories of viruses and bacteria encountered in the past, regulate inflammation, and subdue hyperactive immune responses. The thymus gland is where T cells are born and trained, exposing them to proteins made by thymus cells that mimic various tissues throughout the body. These are proteins they would encounter once they leave the thymus gland.

The study shows that these “teacher” cells use various transcription factors—proteins that drive the expression of genes unique to specific tissues. When they do so, the mimetic cells adopt the identities of tissues such as skin, lung, liver, or intestine. “Think of it as having your body recreated in the thymus,” explains Diane Mathis, professor of immunology at Harvard, in a statement. The findings, Mathis adds, shed light on how the adaptive immune system acquires its ability to discern friend from foe.

The work shows that T cells-in-training that mistakenly react against self-proteins either receive a command to self-destruct or are repurposed into other types of T cells that restrain other immune cells from attacking. Until now, the elimination of self-reactive T cells was thought to be regulated largely by a single protein called AIRE. Defects in this protein can lead to a serious immune syndrome characterized by the development of multiple types of autoimmune disorders.

Mathis and Michelson found many cells in the thymus that did not express the AIRE protein but were still capable of adopting the identities of different tissue types. The researchers say that the newly identified mimetic cells probably have roles in various autoimmune diseases associated with the tissue types they mimic. An investigation is planned to test that hypothesis.

“We think it’s an exciting discovery that may open up a whole new vision of how certain types of autoimmune diseases arise and, more broadly, of the origins of autoimmunity,” Mathis adds.

The researchers say their next steps include acquiring a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms that affect T cell education. They intend to continue studying the association between individual mimetic cell types and T cell function and dysfunction.

The study is published online in the journal Cell.