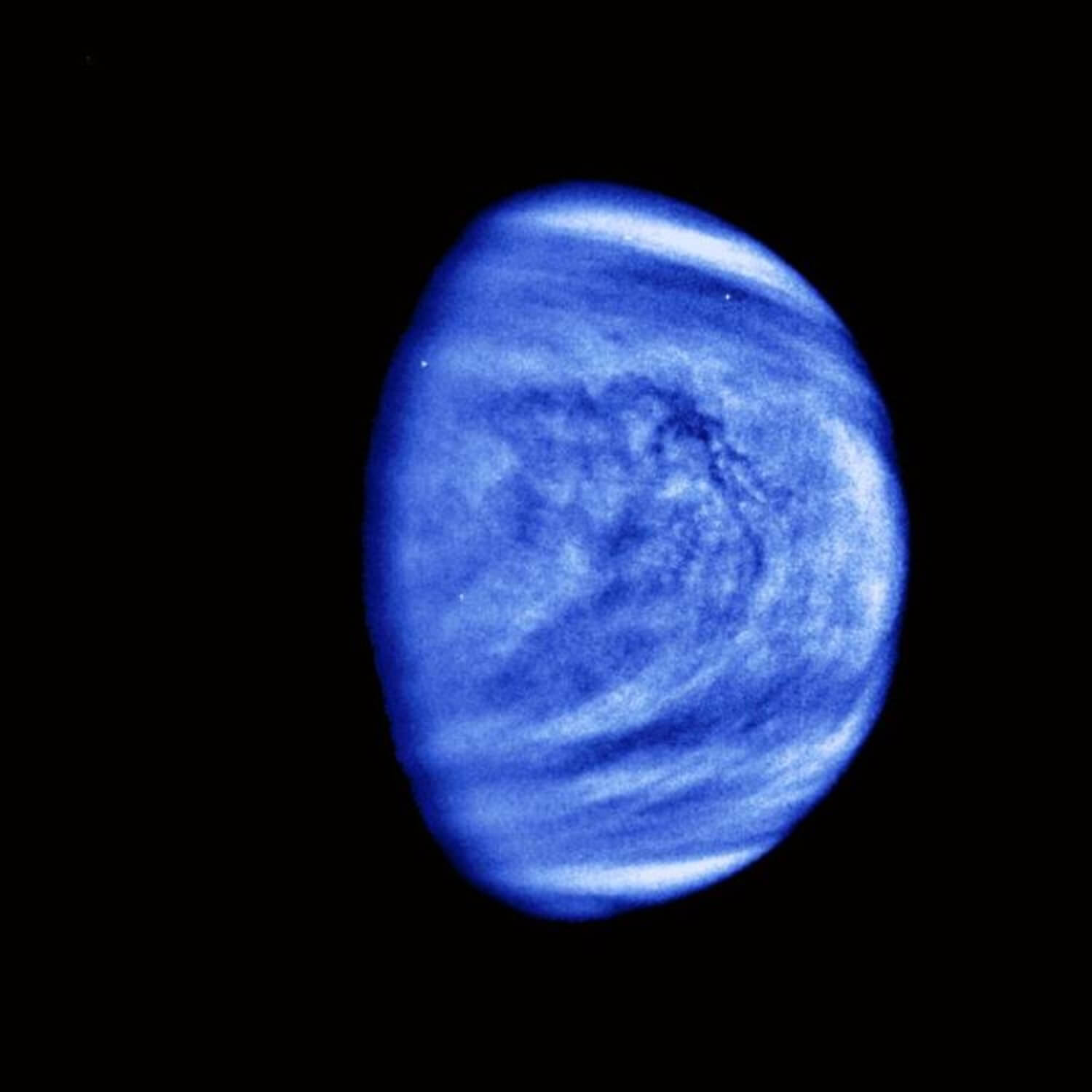

BOULDER, Colo. — Venus, often dubbed Earth’s twin because of its similar size, might not be as electrically charged as some have speculated. For nearly 40 years, scientists have debated whether lightning strikes on Venus, but recent findings may finally offer some clarity. University of Colorado, Boulder researchers have discovered new data that suggests lightning might be a rare event on the second planet from the Sun.

“There’s been debate about lightning on Venus for close to 40 years,” says study lead author Harriet George, a postdoctoral researcher at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP), in a university release. “Hopefully, with our newly available data, we can help to reconcile that debate.”

What makes Venus so intriguing?

Venus, while being about the same size as Earth, is vastly different in terms of its atmosphere. Its thick, carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere triggers a runaway greenhouse effect, creating conditions so intense that temperatures can reach up to 900 degrees Fahrenheit. This extreme heat combined with the planet’s high atmospheric pressures has made it impossible for spacecraft to last more than a few hours on Venus’ surface.

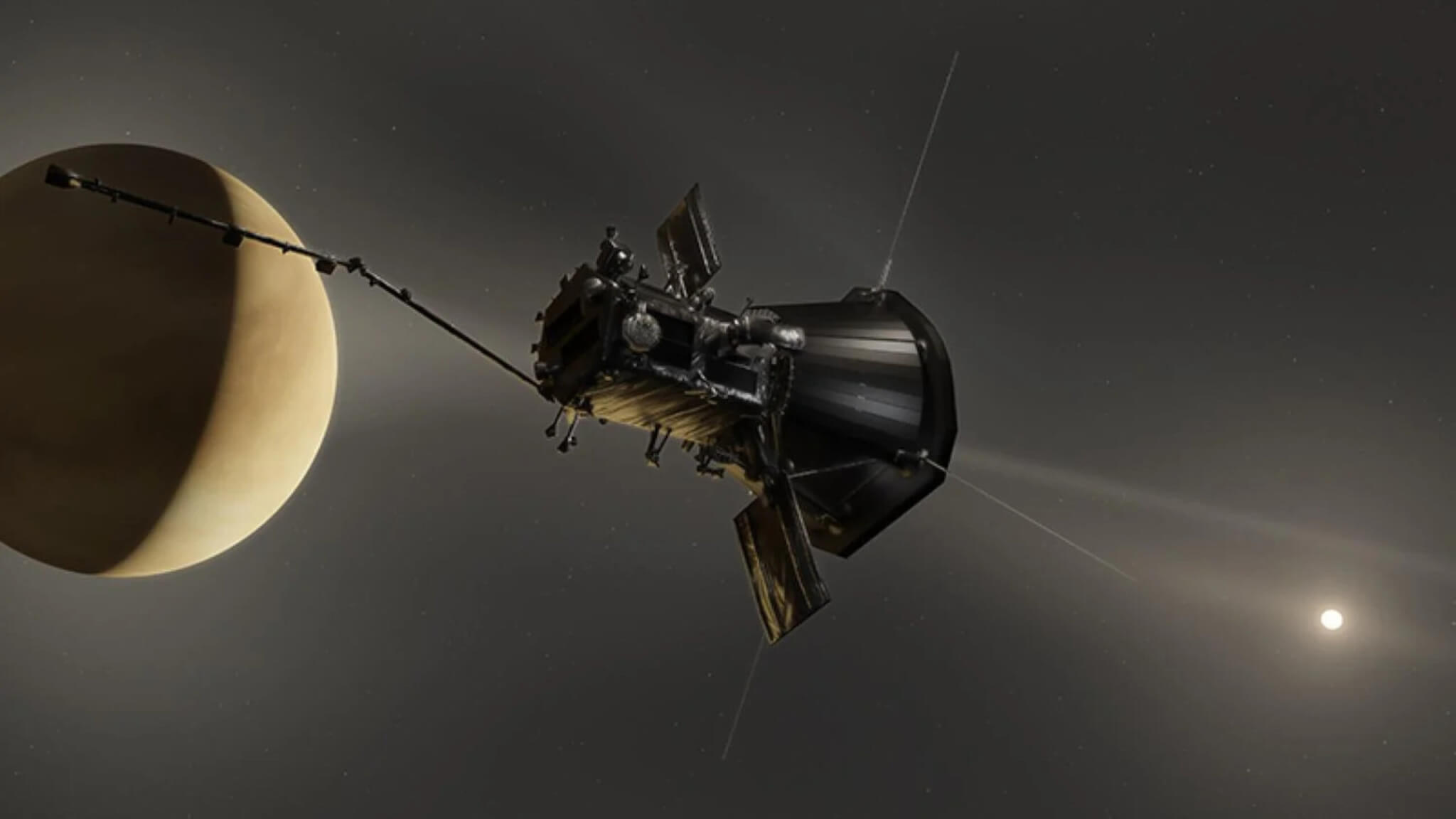

In a unique twist, CU Boulder scientists used NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which was primarily designed to study the Sun, to gather more information about Venus. In February 2021, as the probe neared Venus, it detected several “whistler waves” – energy pulses often associated with lightning on Earth.

After analyzing these whistler waves, researchers found something peculiar. Instead of moving outward into space as lightning-induced waves do on Earth, Venus’ whistlers seemed to move downwards towards the planet. This led researchers to speculate that these waves might not be a result of lightning but might stem from magnetic disturbances surrounding the planet.

What exactly are ‘whistler waves’?

On Earth, lightning can disrupt electrons in the atmosphere, sending out waves into space. Early radio operators could hear these waves as a whistling sound using headphones, earning them the name “whistlers.”

If Venus had a similar pattern, it could mean that the planet experiences lightning strikes about seven times more than Earth. It’s worth noting that lightning has been observed on other planets, including Saturn and Jupiter.

However, the exact origin of Venus’ whistlers remains unclear. One theory is that they might emerge from a process called “magnetic reconnection,” where magnetic fields around Venus get tangled and then explosively re-align.

For a conclusive answer, scientists are eagerly awaiting the Parker Solar Probe’s next flyby of Venus in November 2024.

“Parker Solar Probe is a very capable spacecraft,” says study co-author David Malaspina, assistant professor at LASP and the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences. “Everywhere it goes, it finds something new.”

The 2024 mission will get closer to Venus than ever before, providing researchers with a unique chance to delve deeper into this longstanding mystery.

The study is published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

You might also be interested in:

- Best Of The Best Telescopes For Beginners In 2023: Top 5 Stargazers Most Recommended By Experts

- Broadband satellites are erasing our view of stargazing treasures, astronomers warn

- Venus is geologically active, with plate tectonics just like Earth

Are you looking for this post in Spanish? Después de 40 años, los científicos dicen que Venus podría no tener rayos después de todo