CAMBRIDGE, United Kingdom — Resume writing nowadays can be stressful, but at least no one has to worry about accusations that they’re using the dark arts in a job interview! Researchers from the University of Cambridge have discovered that many women living in England during the 16th and 17th centuries faced accusations of witchcraft — partially because of their jobs.

While men have also been accused of witchcraft over the centuries, the team at Cambridge explains that only roughly 10 to 30 percent of suspected witches were men during this time period across colonial New England, the British Isles, and mainland Europe. There’s likely more than one contributing factor to this shift toward female witch accusations (misogyny, economic hard times). Now, this latest study is offering up yet another reason — employment.

Dr. Philippa Carter believes that the types of employment open to women during this period were much more likely to face allegations of witchcraft and evil-doing — or maleficium.

Currently synonymous with Halloween, horror movies, and Harry Potter far more often than anything related to reality, witches today are largely seen as fun and fictional. Backtrack a few centuries, however, and witches were a very real concern for people living all over Europe and Colonial North America. From common villagers to district officials, people back then saw the world differently, and many blamed witchcraft when crops failed, animals died, or unusual weather set in.

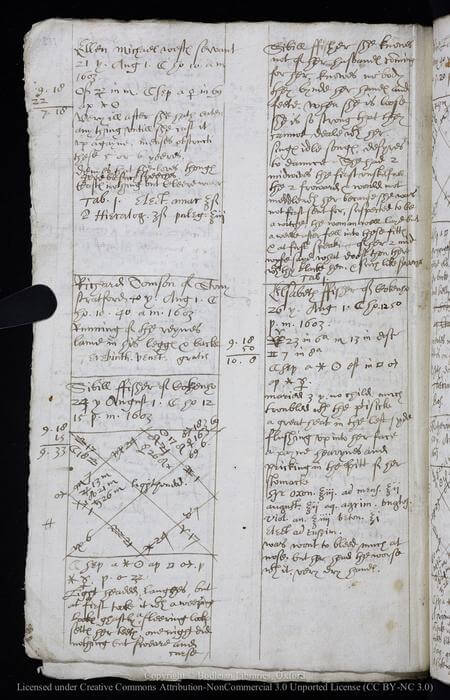

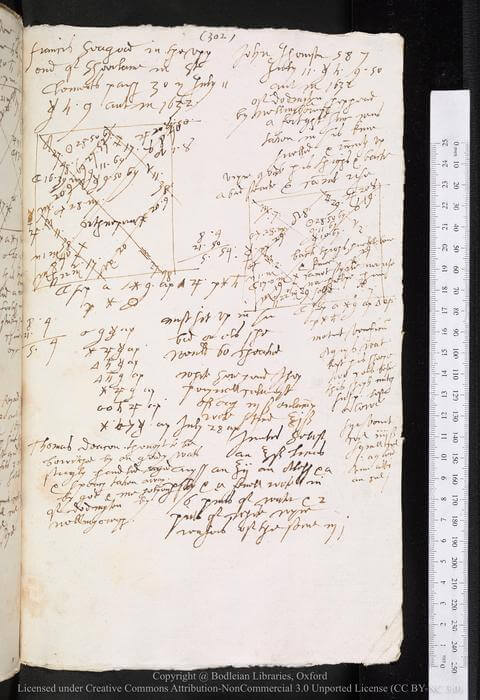

Dr. Carter and her team used the cases of Richard Napier, an astrologer who treated clients in Jacobean England (early 17th century) using star charts and elixirs. Researchers used these notes to search for and analyze links between witchcraft accusations and the occupations of those under suspicion.

Most suspected jobs involved healthcare or childcare, food preparation, dairy production, or livestock care. All of these positions left women exposed to charges of magical sabotage whenever death, disease, or spoilage appeared, causing either suffering or financial loss.

“Natural processes of decay were viewed as ‘corruption’. Corrupt blood made wounds rankle and corrupt milk made foul cheese,” says Carter, from Cambridge’s Department of History and Philosophy of Science, in a university release. “Women’s work saw them become the first line of defense against corruption, and this put them at risk of being labelled as witches when their efforts failed.”

Conversely, men’s typical work at the time involved labor with sturdy or rot-resistant materials like stone, fire, or iron. Many women also had to work more than one job, in most cases in the heart of their communities, which meant crisscrossing between homes, bakehouses, wells, and marketplaces as opposed to working more privately in a field or workshop.

“The frequency of social contact in female occupations increased the chance of becoming embroiled in the rifts or misunderstandings that often underpinned suspicions of witchcraft,” Dr. Carter explains. “Many accusations stemmed from simply being present around the time of another’s misfortune.”

“Women often combined multiple income streams, working in several households to make ends meet: watching children, preparing food, treating invalids. They worked not just in one high-risk sector, but in many at once. It stacked the odds against them.”

As part of a separate, ongoing project at Cambridge, researchers cataloged and digitized more than 80,000 of the case notes written down by the astrologer-doctors Richard Napier and Simon Forman. Napier attended to both the physical and mental health needs of his clients – ordinary people from the area surrounding his Buckinghamshire practice, all the while taking reams of personal notes on their woes. These records now provide a peek into the past, revealing everyday attitudes in relation to magic in the decades before the English Civil War.

“While complaints ranged from heartbreak to toothache, many came to Napier with concerns of having been bewitched by a neighbor,” Dr. Carter explains. “Clients used Napier as a sounding board for these fears, asking him for confirmation from the stars or for amulets to protect them against harm.”

“Most studies of English witchcraft are based on judicial records, often pre-trial interrogations, by which point execution was a real possibility. Napier’s records are less engineered. He seems to have kept these notes only for his own reference,” the study author continues. “The astrologer’s services were accessible to the average person. People might visit him to stress-test their theories or look for magical solutions, rather than attempt a risky lawsuit. Napier’s notes allow us access to witchcraft beliefs at a grassroots level, as suspicions bubbled up in England’s villages.”

Thanks to the recently-digitized casebooks, researchers were able to analyze Napier’s notes for suspected bewitchments, which were ultimately found to make up only 2.5 percent of Napier’s total case files. More specifically, between 1597 and 1634 Napier recorded 1,714 accusations of witchcraft. Most accusers and suspects were women, but the ratio of female suspects was much higher. A total of 802 people identified a suspected witch by name, and 130 of those accusations contained some detail about the suspect’s work.

Notably, six types of employment kept coming up over and over in the notes pertaining to those 130 cases: food services, healthcare, childcare, household management, animal husbandry, and dairying. Those jobs at the time were almost exclusively the domain of women.

Dairy had long been symbolically tied to women as “milk-producers,” with Dr. Carter noting 17 cases of magical spoliation of dairy (16 involved only women). Here’s a specific example: An Alice Gray at the time suspected her neighbors of witchcraft when cheese began to “rise up in bunches like biles [boils] &… heave & wax bitter.” Similarly, failures or issues with brewing and baking were attributed to female witchcraft.

Women were usually in charge of managing food supplies, and with that came a lot of suspicion. Many tales of tit-for-tat maleficium in Napier’s notes apparently originated from spurned requests for food.

“Women were both distributors and procurers of food, and failed food exchanges could seed suspicions,” Dr. Carter adds.

Another woman accused of witchcraft, Joan Gill, gained her magical reputation after her husband drank some milk she had been saving, and the spoon he sipped it with lodged itself in his mouth overnight. So, it seems women were at risk either way; not just denying others food but also supplying it could lead to witchcraft accusations. Another relevant statistic: nine out of 10 suspects who sold food were women, with 25 accusations resulting from a sickness that began after the accuser was fed.

Meanwhile, other women of the time practiced as local healers, often called cunning folk. Essentially magical individuals who stayed away from the darker side of witchcraft, working as a local healer was also very risky for women. Cunning folk were often sought out by people convinced they had been cursed or encountered a witch, but if treatments didn’t produce results, the cunning folk themselves were usually accused of acting in a nefarious manner.

One male customer, troubled with “a great sorenes [in] his privy [private] partes,” told Napier a female healer had “wewitched him” after he sought out a second opinion.

Another very risky line of work was what we now refer to as caring professions (midwifery, elderly care, and childminding), with such positions still being dominated by women today. For instance, 13 suspects had cared for the accuser in her childbed.

Infant mortality, of course, during these centuries was quite high. The loss of a child often motivated allegations. More than 13 percent of all recorded witchcraft accusations that named a suspect involved a victim under 12 years-old.

Loss of sheep and cattle was yet another common cause of accusations. Just over half of livestock workers at the time were women, and yet, this parity can only be seen among accusers (28 men and 28 women) and not suspects (15 men and 91 women).

“Napier’s casebooks suggest that disputes between men over livestock could get deflected onto women,” Dr. Carter says. “An early modern housewife was responsible for managing the health of livestock as well as humans; she made the poultices and syrups used to treat both. When an animal sickened strangely, this could be interpreted as a malefic abuse of her healing skills.”

“Gendered divisions of labor contributed to the predominance of female witchcraft suspects,” Carter concludes. “In times of crisis, lingering suspicions could erupt as mass denunciations. England’s mid-17th-century witch trials saw hundreds of women executed within the space of three years. Every Halloween we are reminded that the stereotypical witch is a woman. Historically, the riskiness of ‘women’s work’ may be part of the reason why.”

The study is published in the journal Gender & History.

I had said under the Stonehenge article history is changing. It’s not malefic um, although the One mind is aware of sheer undiplomatic ambition. Stray cats also destroy things and can be subject to half the blame.