CAMBRIDGE, United Kingdom — Whether you love it or hate it, there’s no doubt that the British people have quite a sense of humor. A recently discovered manuscript from the 15th century reveals a treasure trove of medieval comedy performances, shedding light on British comedy and the role of minstrels in society. The texts, filled with mockery of kings, priests, and peasants, encourage the audience to get drunk and shock them with slapstick humor. The discovery challenges our understanding of English comic culture between Chaucer and Shakespeare.

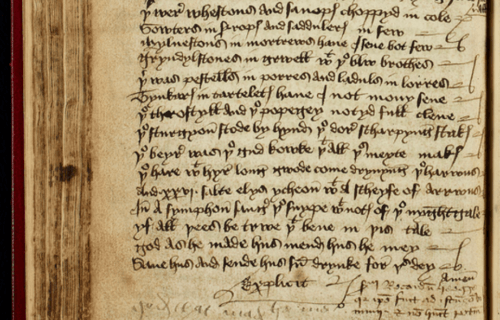

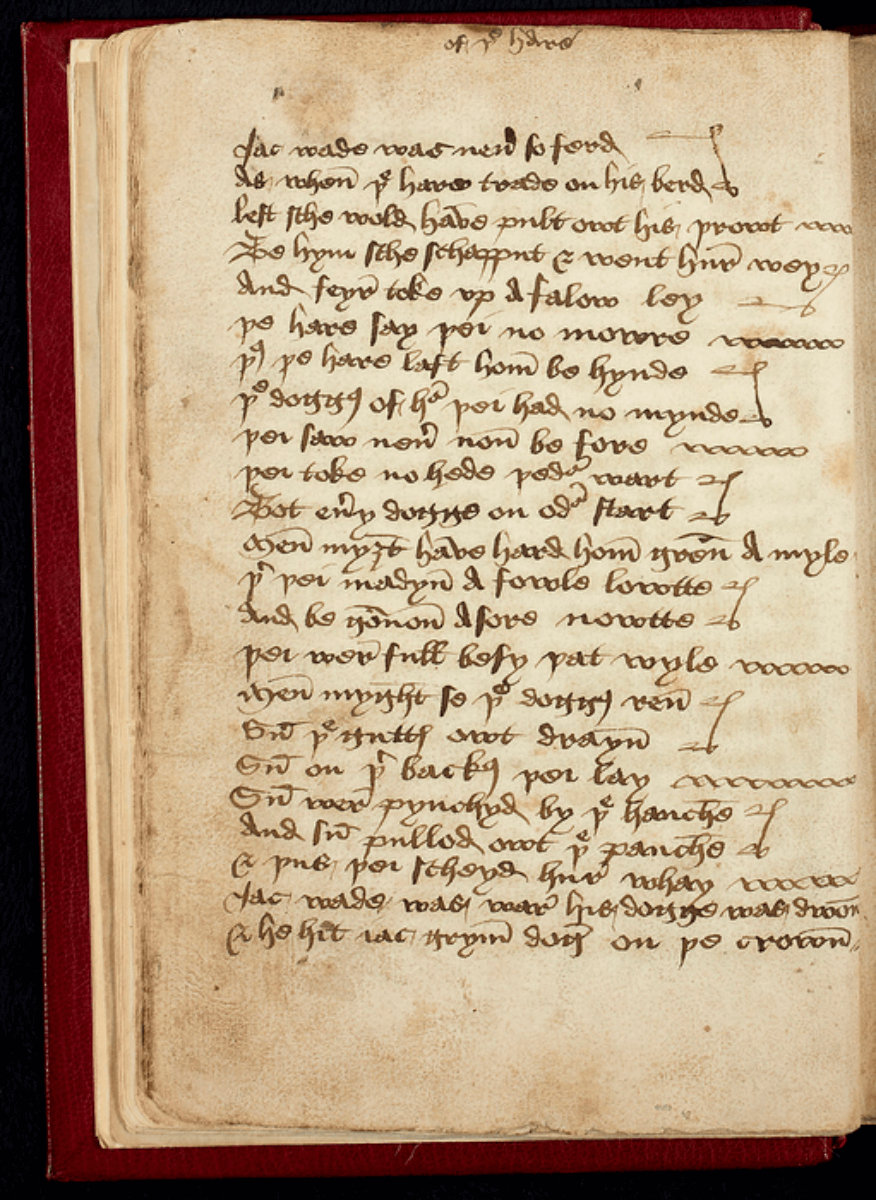

Dr. James Wade, from Cambridge University, stumbled upon the texts while researching at the National Library of Scotland. He noticed a humorous remark by the scribe, Richard Heege, which led him to investigate further. The study focuses on a booklet called the “Heege Manuscript,” containing three texts that offer insight into the lives and work of minstrels.

“Most medieval poetry, song and storytelling has been lost,” Wade says in a university release. “Manuscripts often preserve relics of high art. This is something else. It’s mad and offensive, but just as valuable. Stand-up comedy has always involved taking risks and these texts are risky! They poke fun at everyone, high and low.”

These texts provide the earliest recorded use of “red herring” in English, as well as rare forms of medieval literature and a killer rabbit reminiscent of Monty Python. They offer a glimpse into the comedic culture of the time, poking fun at people from all walks of life. The texts were often performed live by minstrels who entertained audiences at fairs, taverns, and baronial halls. While fictional minstrels are common in medieval literature, references to real-life performers are scarce. The discovery of these texts brings to light the originality and irony of self-made entertainers with little education.

Wade’s study highlights the importance of minstrels’ repertoire, featuring humorous texts designed for live performances. These texts contain in-jokes tailored to local audiences and exhibit a playful awareness of diverse celebratory crowds that minstrels engaged with. The minstrel likely wrote down part of his act to aid his memory, as the nonsensical sequences would have been challenging to recall.

Contrary to previous beliefs that minstrels primarily performed ballads about Robin Hood and chivalric romances, these texts demonstrate a broader comedic range. They encompass satire, irony, nonsense, topical references, and interaction with the audience, creating a comedy feast.

One text, “The Hunting of the Hare,” portrays fictional peasants engaging in absurd high jinks, featuring a scene reminiscent of the “Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog” from Monty Python. Another text includes a mock sermon in Middle English that addresses the audience as “cursed creatures” and incorporates drinking songs.

The texts offer a rare glimpse into the rich oral storytelling and popular entertainment of medieval life. Festive entertainment thrived during this period, demonstrating flourishing social mobility. Minstrels played a significant role in people’s lives across the social hierarchy, and these texts provide valuable insight into the festive atmosphere and entertainment practices of the time.

While more evidence may exist, minstrel writings are unlikely to have survived. Researchers encourage exploring other types of evidence, such as these texts from the Heege Manuscript, to gain a deeper understanding of live performances and the vibrant medieval culture they represented.