NEW YORK — Ants appear to be superior communicators in comparison to humans, a new study suggests. Scientists have discovered a unique processing center in the ant’s brain, not seen in other social animals, which sheds new light on how ants collectively manage food, shelter, and defense for their entire colony. This exceptional ability enables a solitary scout ant to infiltrate a human home and then summon its fellow colony members.

Most traps catch only a handful of ants, but soon the rest mysteriously vanish. This phenomenon has long puzzled entomologists, until now.

“Humans aren’t the only animals with complex societies and communication systems,” says lead author Taylor Hart of The Rockefeller University. “Over the course of evolution, ants have evolved extremely complex olfactory systems compared to other insects, which allows them to communicate using many different types of pheromones that can mean different things.”

Ants perceive these chemicals using their antennae. With origins tracing back to 168 million years ago, when dinosaurs dominated the Earth, there are now over 12,000 ant species. Ants outnumber humans by a million to one, and these findings illuminate their success, revealing how the scents they emit stimulate a specific brain section, altering the behavior of the entire nest.

Ants’ communication nodes can interpret alarm pheromones, or “danger signals” from their peers. It is thought to be a more advanced system than that of honeybees, which rely on several brain parts to react to a single pheromone.

“There seems to be a sensory hub in the ant brain that all the panic-inducing alarm pheromones feed into,” adds corresponding author Daniel Kronauer of The Rockefeller University in a media release.

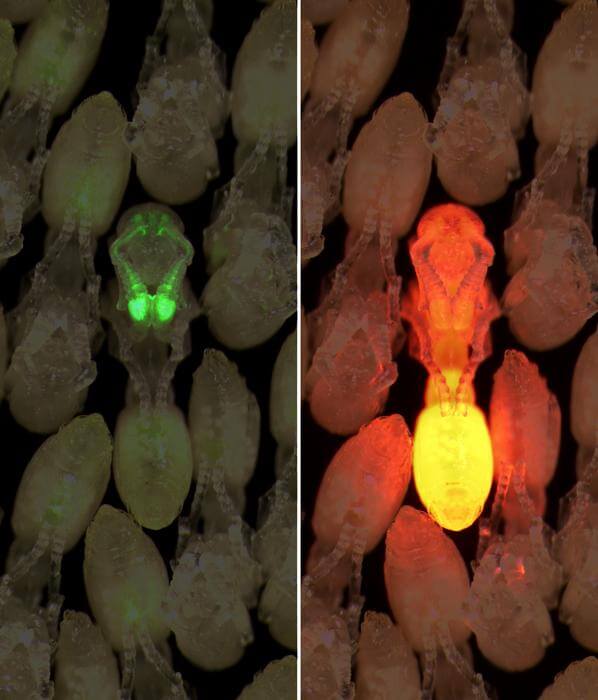

The New York team employed an engineered protein called GCaMP to analyze the brain activity of clonal raider ants exposed to danger signals. The gene functions by attaching itself to calcium ions, which intensify with brain activity. The resultant fluorescent chemical compound can then be scanned using adapted high-resolution microscopes.

Despite only a minor section of the ants’ brains responding to the stimulus, they demonstrated immediate and complex behaviors. These reactions included “panic” activities such as fleeing, evacuating the nest, and relocating offspring to safer locations. Different ant species with varying colony sizes use unique pheromones to communicate a range of messages.

“We think that in the wild, clonal raider ants usually have a colony size of just tens to hundreds of individuals, which is pretty small as far as ant colonies go,” says Hart.

“Frequently, these small colonies tend to have panic responses as their alarm behavior because their main goal is to get away and survive. They can’t risk a lot of individuals. Army ants, the cousins of the clonal raider ants, have massive colonies—hundreds of thousands or millions of individuals—and they can be much more aggressive.”

Regardless of the species, ants within a colony divide themselves by caste and role, and ants within different castes and roles exhibit slightly varying anatomy. The researchers chose clonal raider ants for their study because they are easy to manage, and they selected only female workers to ensure consistency and thereby make it simpler to observe prevalent patterns.

With a clearer understanding of the neural differences between castes, sexes, and roles, researchers hope to better comprehend exactly how different ant brains process the same signals.

“We can start to look at how these sensory representations are similar or different between ants,” says Hart.

“We’re looking at division of labor. Why do individuals that are genetically the same assume different tasks in the colony? How does this division of labor work?” Kronauer concludes.

The study is published in the journal Cell.

Ants can ‘tell’ their whole colony to play dead!

The excellent communication skills of ants can be summed up by one crafty species on Australia’s Kangaroo Island. Scientists found an entire colony of sneaky ants who all play dead to fool predators.

The team were originally checking pygmy-possum and bat nest boxes when they accidentally discovered a colony of Polyrhachis femorata ants that appeared to be dead, until one “messed up” and moved.

Researchers believe all of the ants were playing dead as a defensive strategy to avoid potential danger. Published in the Australian Journal of Zoology, this is the first time that a whole colony of ants has been recorded feigning death, and the first record of the Polyrhachis femorata ant species for South Australia.

“The mimicry was perfect,” Petit says in a university release. “When we opened the box, we saw all these dead ants…and then one moved slightly.”

“This sort of defensive immobility is known among only a few ant species – in individuals or specific casts – but we don’t know of other instances when it’s been observed for entire colonies,” Petit continues.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.