NEW YORK — Researchers from Columbia University are revolutionizing forensic investigations and could potentially impact numerous cold cases. Engineers from the Ivy League school used artificial intelligence to discover that fingerprints from different fingers of the same person ARE NOT unique and unmatchable, challenging a long-standing presumption in forensic science.

Gabe Guo, a senior at Columbia University’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences who has no prior background in forensics, spearheaded this innovative research. Guo and his team utilized a public U.S. government database containing around 60,000 fingerprints. They fed these fingerprints into an artificial intelligence-based system known as a deep contrastive network, which they designed by modifying a state-of-the-art framework.

The AI system was trained to discern whether pairs of fingerprints, some from the same individuals but different fingers, belonged to the same person or not. Impressively, the system achieved a 77-percent accuracy rate for single pairs, which significantly increased with multiple pairs, suggesting a potential ten-fold improvement in forensic efficiency.

The study’s initial findings were met with skepticism from the forensics community. A leading forensics journal rejected the team’s submission, citing the well-accepted belief in the uniqueness of every fingerprint. However, undeterred, the team enhanced their AI system with more data, leading to improved results.

“I don’t normally argue editorial decisions, but this finding was too important to ignore,” says Hod Lipson, who is the James and Sally Scapa Professor of Innovation in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and co-director of the Makerspace Facility, in a university release. “If this information tips the balance, then I imagine that cold cases could be revived, and even that innocent people could be acquitted.”

One of the critical questions raised was what alternative information the AI used that had been overlooked by forensic experts for decades.

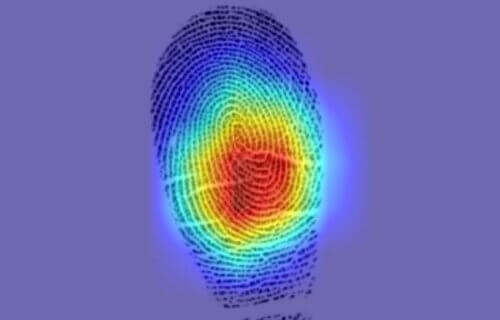

“The AI was not using ‘minutiae,’ which are the branchings and endpoints in fingerprint ridges — the patterns used in traditional fingerprint comparison,” says Guo, who began the study as a first-year student at Columbia Engineering in 2021. “Instead, it was using something else, related to the angles and curvatures of the swirls and loops in the center of the fingerprint.”

Researchers acknowledge that this is just the beginning. They envision significant improvements in the system’s performance with larger datasets. Columbia researchers also noted the need for more comprehensive datasets to validate the AI’s performance across different genders and races.

“Just imagine how well this will perform once it’s trained on millions, instead of thousands of fingerprints,” notes Aniv Ray, senior at Columbia Engineering.

This discovery exemplifies the potential of AI in revolutionizing well-established fields.

“Many people think that AI cannot really make new discoveries — that it just regurgitates knowledge,” says Lipson. “But this research is an example of how even a fairly simple AI, given a fairly plain dataset that the research community has had lying around for years, can provide insights that have eluded experts for decades.”

“Even more exciting is the fact that an undergraduate student, with no background in forensics whatsoever, can use AI to successfully challenge a widely held belief of an entire field. We are about to experience an explosion of AI-led scientific discovery by non-experts, and the expert community, including academia, needs to get ready,” Lipson continues.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances.