COPENHAGEN, Denmark — Growing artificial skin could stop skin cancer in its tracks, according to researchers from the University of Copenhagen. The recent skin model could help doctors understand how cancer damages skin structures and hijacks healthy cells.

In a healthy body, damage to the skin does not prompt skin cells to invade the hypodermis. Rather, they respond by producing new layers of skin. In the presence of cancer, however, skin cells no longer keep to one area and start to test the boundaries between multiple layers. These actions can lead to invasive growth.

Blocking invasive growth would curb the spread of skin cancer, and the authors of this study believe this can be done through the TGF beta pathway.

“We have been studying one of the cells’ signaling pathways, the so-called TGF beta pathway. This pathway plays a critical role in the cell’s communication with its surroundings, and it controls e.g. cell growth and cell division,” explains Hans Wandall, a professor in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, in a media release. “If these mechanisms are damaged, the cell may turn into a cancer cell and invade the surrounding tissue.”

There are already drugs available that can block the TGF signaling pathway, the next step is to test it in a skin cancer model. That’s where this new artificial skin comes into the picture.

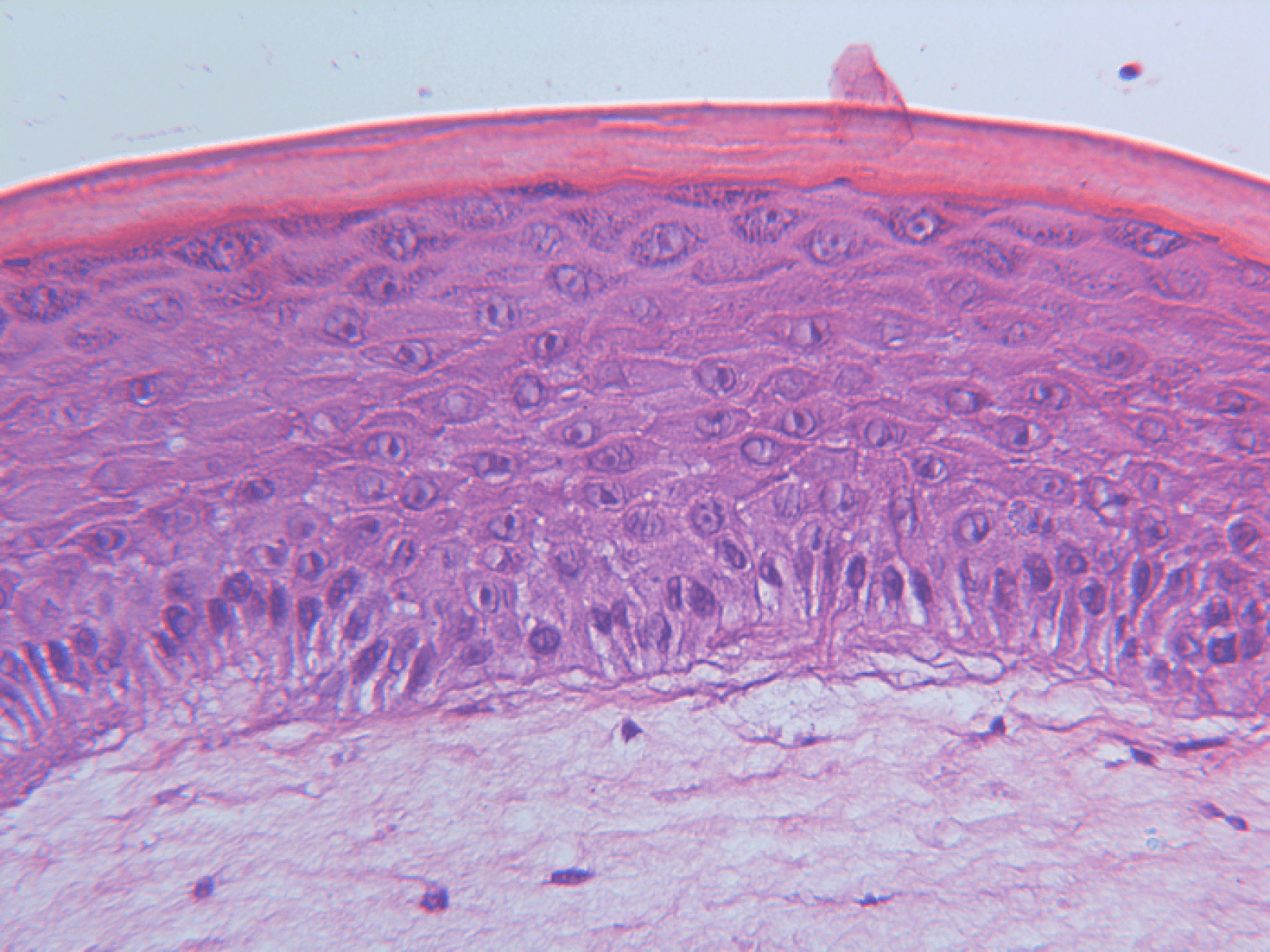

So far, the artificial skin created by researchers is the closest to resembling and acting like real human skin. The artificial version uses genetically modified human skin cells that were made from subcutaneous tissue. Like real human skin, these cells grow in layers. The model also allows researchers to quickly make genetic changes, which would help them view skin development under multiple skin disorders, not just skin cancer.

“By using artificial human skin we are past the potentially problematic obstacle of whether results from tests on mice models can be transferred to human tissue. Previously, we used mice models in most studies of this kind. Instead, we can now conclude that these substances probably are not harmful and could work in practice, because the artificial skin means that we are closer to human reality,” says Wandall.

The artificial skin does resemble the skin models used to test cosmetics in the European Union, though it does not give researchers the ability to test the effect of a drug on the entire organism. Instead, it focuses on an individual organ like the skin to get an in-depth look at how molecules work and what happens during skin damage.

The study is published in the journal Science Signaling.

You might also be interested in:

- Robotic flesh? Scientists create living skin for covering robots

- New immunotherapy shows promise in fighting aggressive skin cancer

- Best Vitamins For Healthy Skin: Top 5 Supplements Most Recommended By Experts