GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Space travel severely impacts astronauts’ brains, necessitating a significant recovery period after returning to Earth. A new study suggests that astronauts should wait three years following long missions to allow for physiological changes in their brains to reverse.

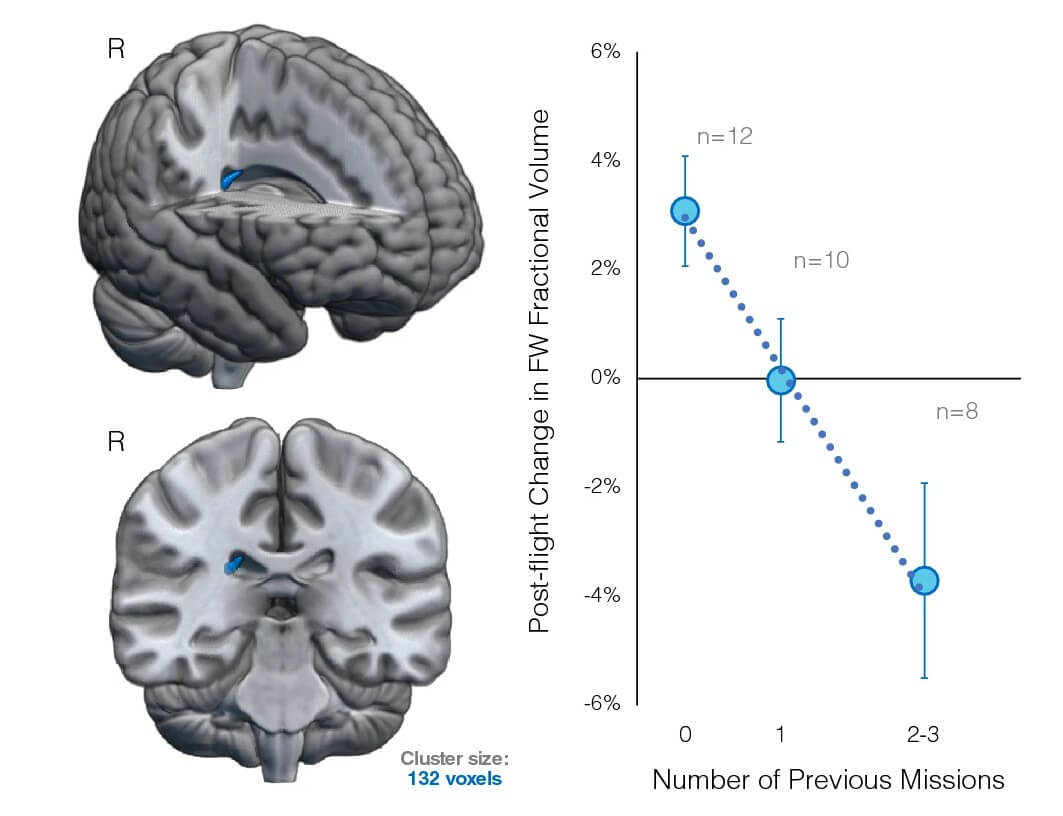

Researchers analyzed brain scans from 30 astronauts, taken both pre and post-space travel. They discovered a marked expansion of the brain’s ventricles in those who undertook missions lasting at least six months. Given this level of expansion, a recovery period of less than three years may be inadequate.

Ventricles are fluid-filled cavities within the brain, filled with cerebrospinal fluid that serves to protect, nourish, and remove waste from the brain. Under normal gravity conditions, bodily mechanisms distribute fluids evenly throughout the body. However, in the absence of gravity, these fluids shift upwards, causing the brain to ascend within the skull and resulting in ventricular expansion.

This expansion compresses the brain, potentially resulting in the destruction or damage of brain tissue. Fortunately, the study revealed no change in the brain structure of individuals who spent less than two weeks in space, offering positive implications for the future of space tourism.

“We found that the more time people spent in space, the larger their ventricles became. Many astronauts travel to space more than one time, and our study shows it takes about three years between flights for the ventricles to fully recover,” says Dr. Rachael Seidler, a Professor of Applied Physiology and Kinesiology at the University of Florida, in a media release. “The biggest jump comes when you go from two weeks to six months in space. There is no measurable change in the ventricles’ volume after only two weeks.”

That ventricular expansion is the most lasting change observed in the brain due to spaceflight.

“We don’t yet know for sure what the long-term consequences of this is on the health and behavioral health of space travelers. So, allowing the brain time to recover seems like a good idea,” adds Dr. Seidler.

The astronauts in the study varied in their space travel durations: eight embarked on two-week missions, 18 were on six-month missions, and four were in space for roughly a year. The study observed that ventricular enlargement plateaued after six months. This finding is encouraging news for the burgeoning field of space tourism, as shorter space trips seem to induce minimal physiological changes to the brain.

“We were happy to see that the changes don’t increase exponentially, considering we will eventually have people in space for longer periods,” concludes Dr. Seidler.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

South West News Service writer Alice Clifford contributed to this report.

Maybe they could wear tinfoil hats while they’re out there.

.. and thus we evolve into “Cone-heads”.