LONDON — Early humans in what is now the Arabian desert were baking bread and cooking meat thousands of years ago, according to new research. Advanced analyses of ancient grinding tools reveal evidence of plant, pigment, and bone processing in Northern Saudi Arabia during the Neolithic period — also known as the New Stone Age.

Studies indicate that the now-desert region was considerably wetter and greener in the past, allowing Neolithic communities access to water and fresh game. However, the region’s current dryness preserves minimal organic matter, challenging reconstructions of Neolithic lifestyles.

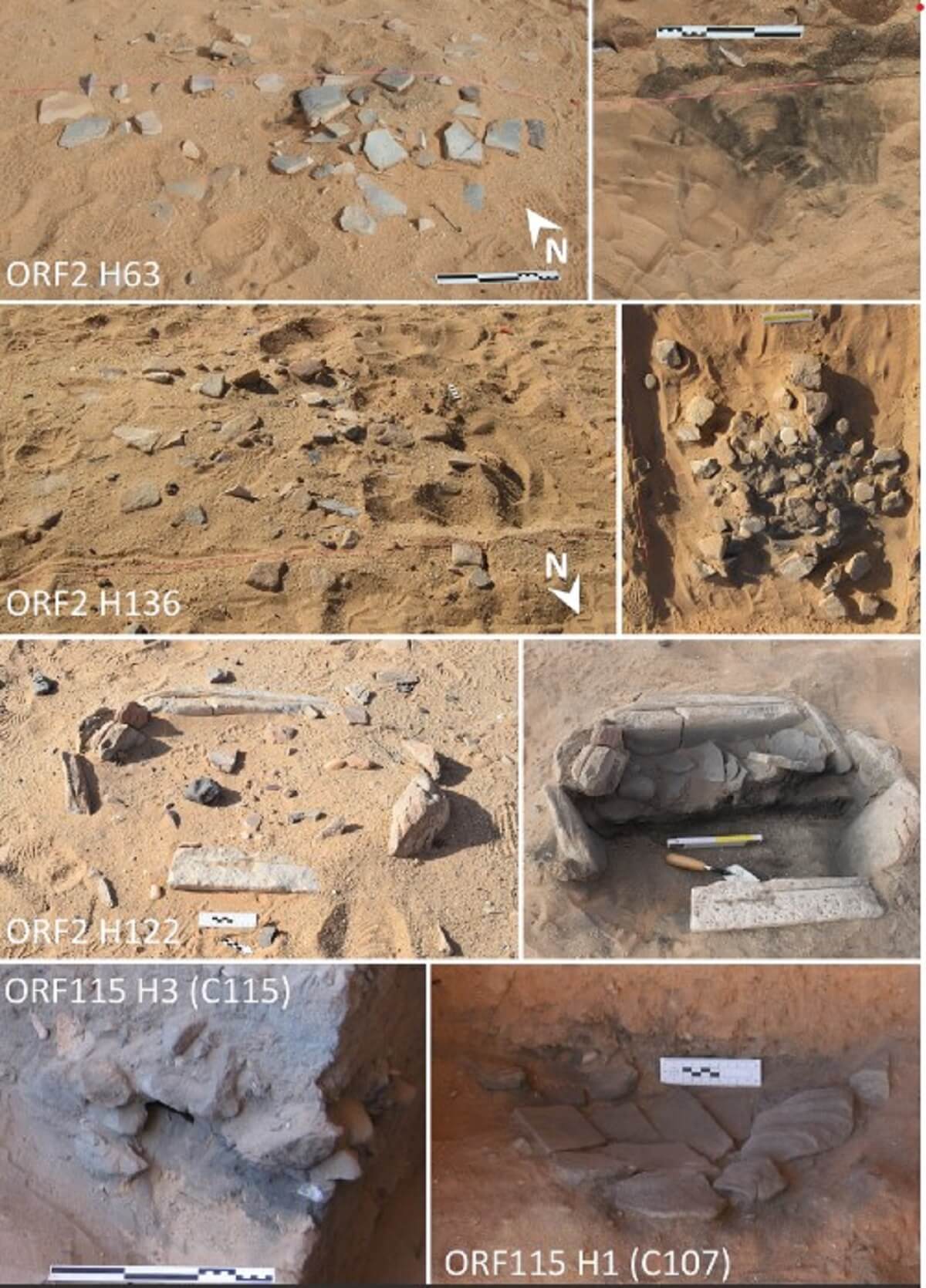

A team of researchers, including scientists from University College London, conducted a detailed use-wear analysis on grinding tools excavated from Jebel Oraf in the Nefud desert of Saudi Arabia. Their findings shed light on a relatively unknown segment of human history.

The study determined that these tools were used to process bone, pigment, and plants. They were also repurposed for various tasks throughout their lifespan before ultimately being shattered and placed on hearths.

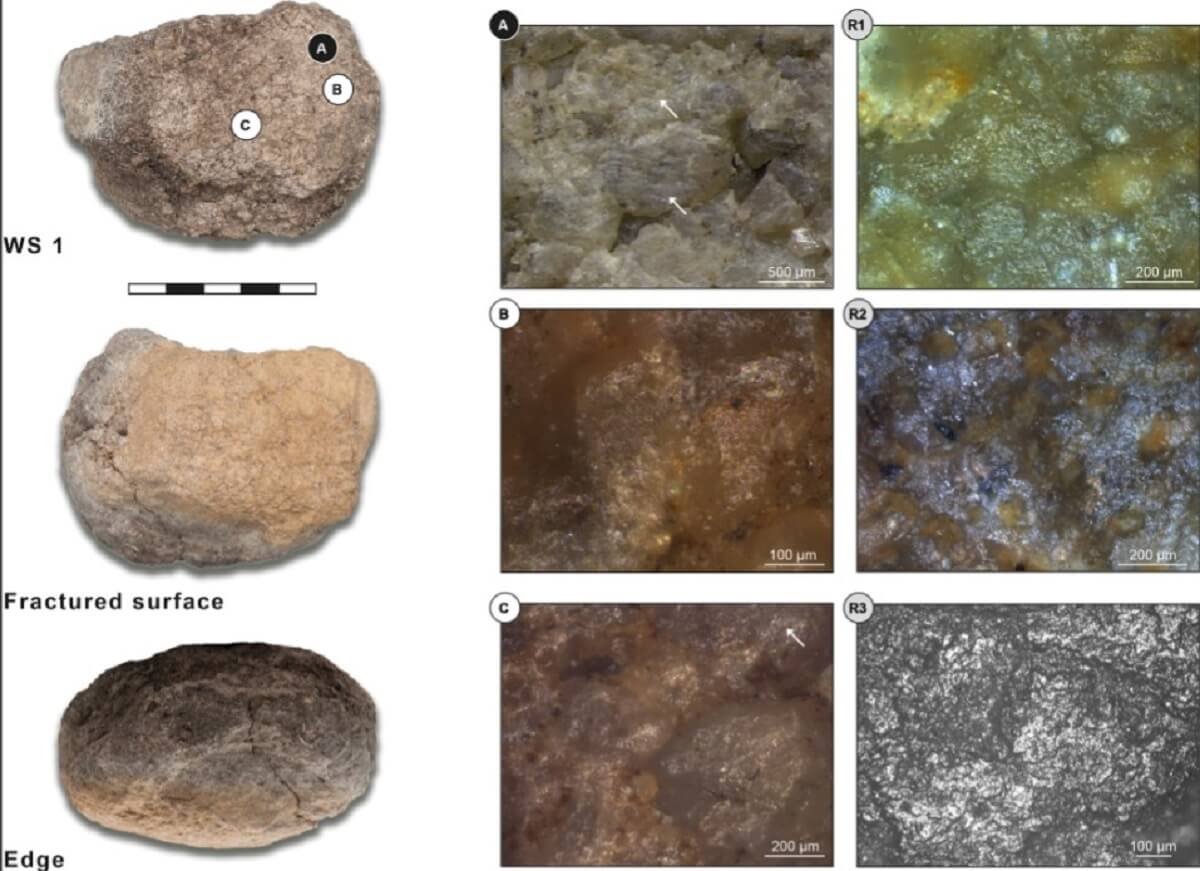

By using high-powered microscopes, the researchers compared use-wear patterns on the archaeological tools to those on experimental ones. Through experimentation, they found that grinding different materials, such as grains, bone, or pigment, left unique macro and micro traces on the tool’s surface. These traces, including fractures, edge roundings, leveled areas, striations, and various polish types, were also present on the Neolithic tools. This allowed the team to discern the materials being processed.

Although prior evidence showed meat consumption at Jebel Oraf, the newly discovered wear patterns suggest that meat and bones underwent preliminary processing on grindstones. This indicates the likelihood that bones were cracked open to extract the marrow.

The tools were also used to process plants. Although no signs of domesticated grains have been found in northern Arabia from that era, the researchers believe wild plants were milled and potentially baked into basic bread.

WS: working surface; White letters on black dots: Low magnification photos; Black letters on white dots: High magnification photos; Black letters/numbers on grey dots: Replica photos. (A) Short, shallow, and parallel striations (white arrows); (B) Moderately reflective, granular polish; (C) Shallow, parallel, and narrow micro-striations (white arrow); (R1) Experimental replica used for grinding dry einkorn wheat for 600 minutes; (R2) Experimental replica used for grinding dry emmer wheat for 600 minutes; (R3) Experimental replica used for grinding dry sorghum for 360 minutes. (R1, R2) Micrographs of the actual tools. Reference collection of the Laboratory for Material Culture Studies, Leiden University; (R3) Micrograph of Provil Novo® mould. Reference collection of the Institute of Heritage Science, National Research Council of Italy, Rome.

(credit: Giulio LucariniMaria Guagnin, Michael Petraglia)

“The hearths where we found the grinding tools were extremely short-lived, and people may have been very mobile – breads would have made a good and easily transportable food for them,” says Dr. Maria Guagnin, co-lead author from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Germany, in a media release. “Breads would have been a convenient, transportable food source for them.”

Additionally, the team identified evidence of pigment processing, which they theorize could be connected to Neolithic artworks. The scale of pigment grinding discovered indicates a possibility of more Neolithic-painted rock art than what has been found to date.

“It is clear grinding tools were important for the Neolithic occupants of Jebel Oraf. Many were heavily used, and some even had holes in them that suggest they were transported,” says co-lead author Dr. Giulio Lucarini, from the National Research Council of Italy. “That means people carried heavy grinding tools with them and their functionality must have been an important element in daily life.”

The study is published in the journal PLoS ONE.

You might also be interested in:

- Best English Muffins: Top 5 Brands Plus Their Most Expert-Beloved Flavors

- Ancient Process Turns Plant-Based Cheeses Into Something People Actually Want To Eat

- Were our ancestors cannibals? Ancient bones reveal early humans ‘butchered one another’

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.