CINCINNATI — Godzilla isn’t the only monster that terrorized Japanese waters. University of Cincinnati scientists have uncovered a mosasaur, a massive marine reptile, that lived 72 million years ago, resembling the size of a great white shark. According to researchers, this prehistoric creature roamed the Pacific seas, inspiring awe and fear with its formidable size and unique features.

Mosasaurs, extinct giants of the sea, were the apex predators of the prehistoric oceans. They thrived during the late Cretaceous period, the era of the Tyrannosaurus rex, but met their end alongside the dinosaurs 66 million years ago due to a catastrophic asteroid impact.

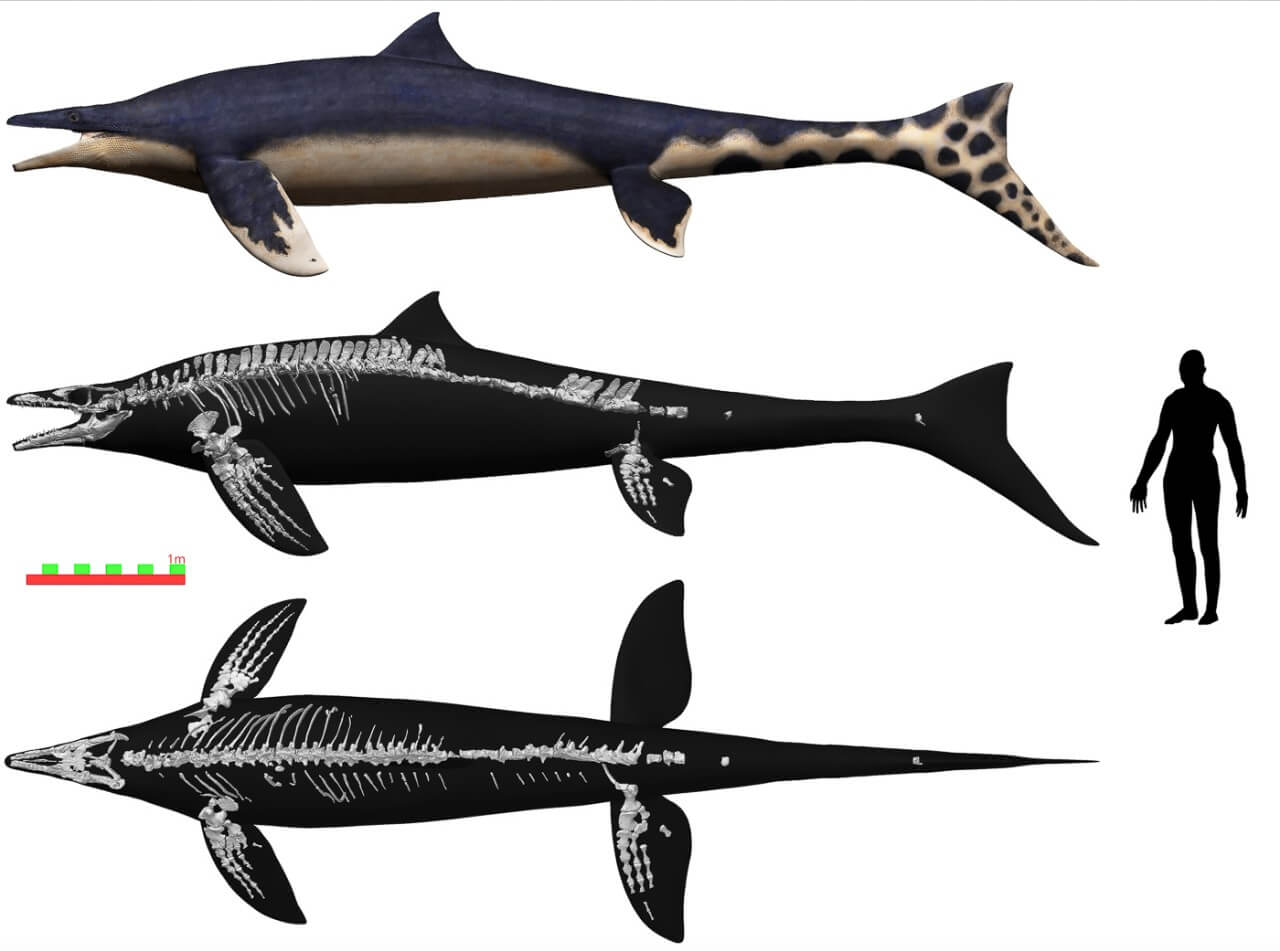

The newly discovered mosasaur, named Wakayama Soryu, meaning “blue dragon,” after the Japanese prefecture where it was found, exhibits characteristics that set it apart from its kin. Notably, it possessed extra-long rear flippers and a dorsal fin similar to that of a shark, which would have enhanced its agility and speed in the water.

Study author Takuya Konishi, an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati and an expert in ancient marine reptiles, expressed his surprise at this discovery.

“I thought I knew them quite well by now,” says Konishi in a university release. “Immediately it was something I had never seen before.”

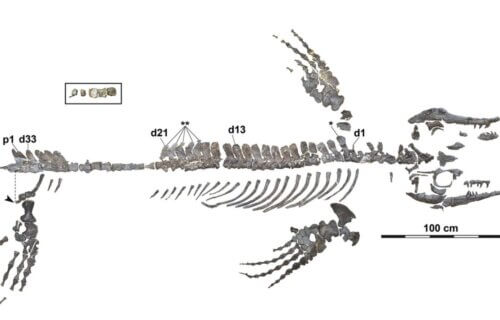

This specimen, the most complete mosasaur skeleton ever found in Japan or the northwestern Pacific, showcases a unique morphology with rear flippers longer than its front ones and a crocodile-like head.

“In this case, it was nearly the entire specimen, which was astounding,” notes Konishi.

The discovery was made along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama by study co-author Akihiro Misaki in 2006, initially mistaken for a dark fossil in the sandstone. After a closer examination, it was revealed to be a nearly complete mosasaur skeleton.

Researchers have classified this specimen into the subfamily Mosasaurinae and named it Megapterygius wakayamaensis, which translates to “large winged.” This name reflects the mosasaur’s enormous flippers, which were theorized to be used for propulsion, a unique swimming technique among mosasaurs and virtually all other animals.

The Wakayama Soryu’s large front fins may have aided in rapid maneuvering, while its large rear fins might have provided the ability to dive or surface efficiently. Its tail, like other mosasaurs, likely generated powerful acceleration for hunting fish. This combination of hydrodynamic surfaces poses intriguing questions about its swimming capabilities.

“It’s a question just how all five of these hydrodynamic surfaces were used. Which were for steering? Which for propulsion?” says Konishi. “It opens a whole can of worms that challenges our understanding of how mosasaurs swim.”

Unique among mosasaurs, the Wakayama Soryu also had a dorsal fin, inferred from the orientation of the neural spines along its vertebrae. This feature draws parallels to modern toothed whales, like dolphins and porpoises, which also have prominent dorsal fins.

The preparation of the fossil was a meticulous process, taking five years to remove the surrounding sandstone matrix. This effort was supported by grants from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. These funds were crucial in enabling researchers to compare this unique specimen with mosasaurs from around the world.

The study is published in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

You might also be interested in:

- Shark graveyard may reveal a new shark species at the bottom of the ocean

- 200-million-year-old mass extinction event may be happening again right now

- Massive skull fossil points to a prehistoric sea monster being Earth’s first giant