LOS ANGELES — Is Earth undergoing a mass extinction event right now? Researchers from the University of Southern California believe so, as their new study reveals stunning information about what caused a similar catastrophic event on Earth hundreds of millions of years ago.

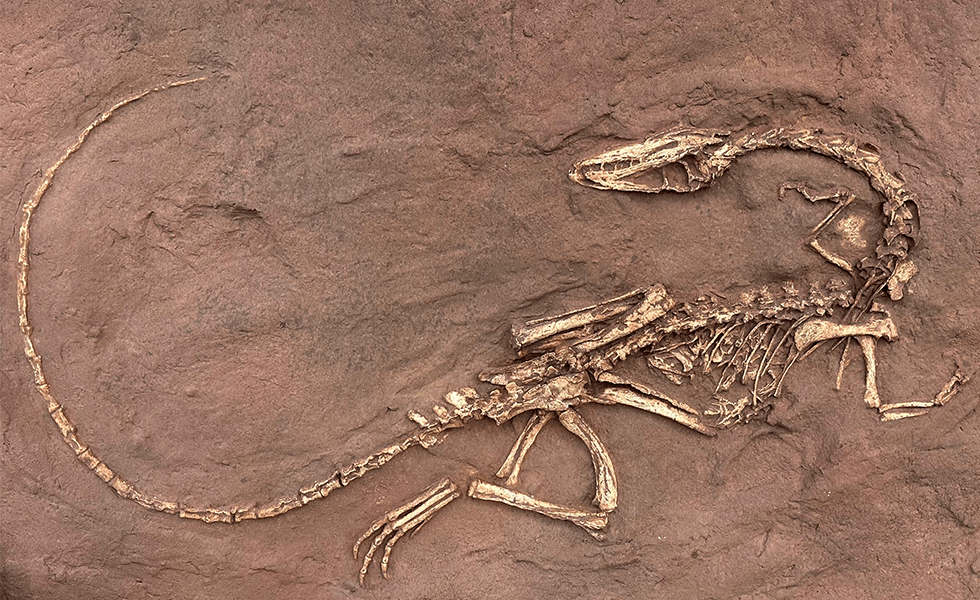

Approximately 200 million years ago, Earth faced its fourth major mass extinction, triggered by a surge in greenhouse gases stemming from volcanic activity. This event led to rapid global warming, reshaping the planet’s biosphere and marking the transition from the Triassic to the Jurassic period. Today, many scientists believe that Earth is undergoing another mass extinction, largely due to similar climate shifts.

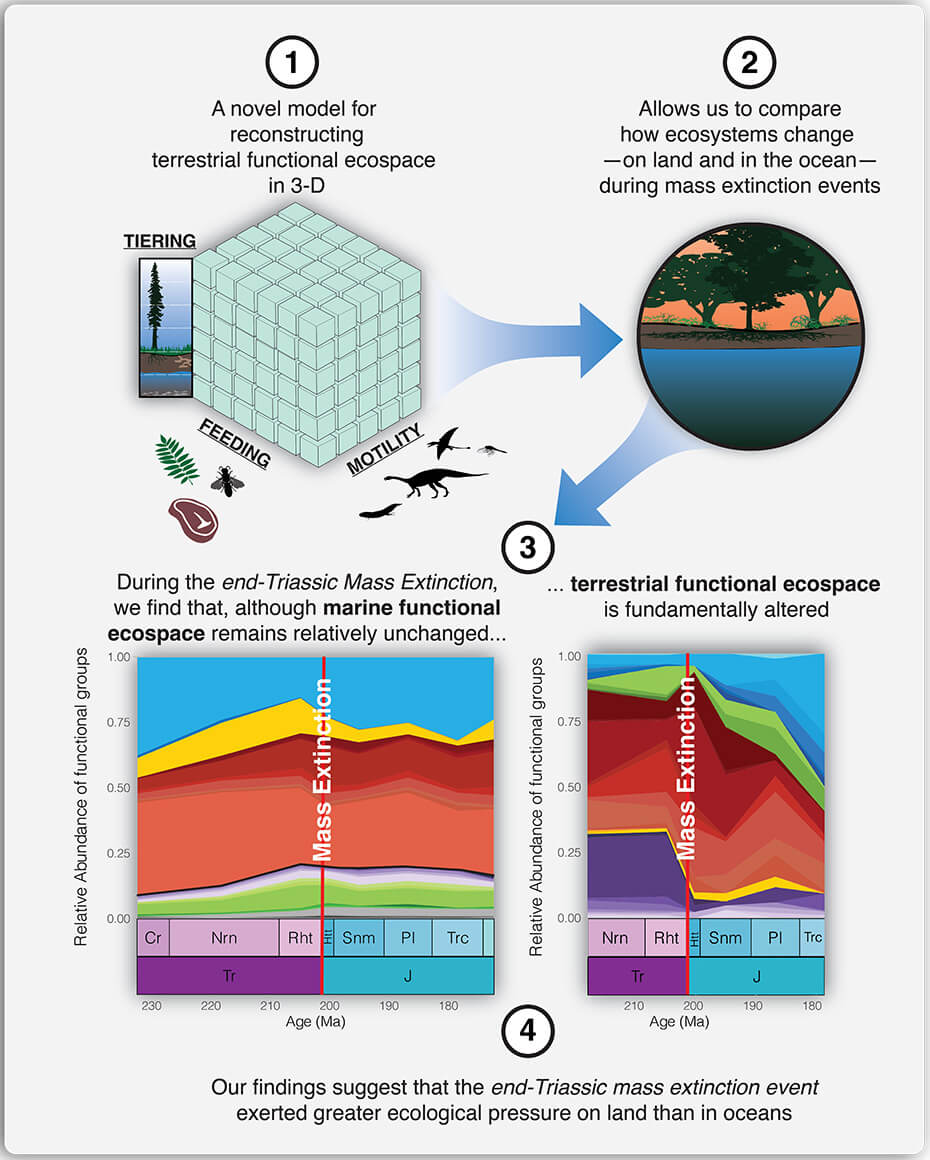

USC Dornsife Earth scientists adopted a unique approach to assess the impact of this extinction event on both land and ocean ecosystems. They utilized an innovative “ecospace framework” method, categorizing animals beyond species and considering ecological roles and behaviors, spanning from marine predators to terrestrial herbivores.

“We wanted to understand not just who survived and who didn’t, but how the roles that different species played in the ecosystem changed,” says study senior author David Bottjer, professor of Earth sciences, biological sciences and environmental studies at USC Dornsife, in a university release. “This approach helps us see the broader, interconnected ecological picture.”

The collaborative study between USC Dornsife and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County unveils striking insights into the impact of the extinction event on marine and terrestrial ecosystems. The findings highlighted a significant contrast between the two realms: while both suffered, land-based ecosystems bore a more severe and prolonged impact compared to marine ecosystems.

In the oceans, nearly 71 percent of species categories disappeared, yet the overall structure exhibited resilience, with predators like sharks and filter feeders bouncing back despite severe losses. Conversely, on land, a staggering 96 percent of terrestrial categories went extinct, dramatically altering Earth’s life landscape. Large herbivores and small predators faced significant population changes and role shifts within the ecosystem.

“This contrast between land and sea tells us about the different ways ecosystems respond to catastrophic events,” says study co-lead author Alison Cribb, who earned her PhD in geological sciences at USC Dornsife and is now at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom. “It also raises important questions about the interplay of biodiversity and ecological resilience.”

The study’s findings also have direct implications for contemporary environmental challenges.

“Understanding past mass extinctions helps us to predict and possibly soften the impacts of current and future environmental crises,” explains study co-lead author Kiersten Formoso, who is finishing her doctoral studies in vertebrate paleobiology at USC Dornsife and will soon move to a position at Rutgers University.

Drawing parallels between the end-Triassic warming and today’s climate change, Bottjer notes, “We’re seeing similar patterns now — rapid climate change, loss of biodiversity. Learning how ecosystems responded in the past can inform our conservation efforts today.”

The research, employing the ecospace framework, offers a fresh perspective on ancient life, expounding on not just fossil identification but the functioning of ancient ecosystems.

Looking ahead, scientists aim to delve deeper into how species and ecosystems recovered post-extinction, paralleling these ancient events with current biodiversity loss due to climate change. Future studies will also explore ecospace dynamics across other periods of profound environmental change in Earth’s history.

Altogether, this study, conceived and conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlights unique conditions that fostered collaborative research involving experts across various paleobiological fields.

“This produced unique conditions that fostered and led to development and completion of this research involving individuals with expertise across a broad variety of paleobiological fields, from microbes to invertebrates to vertebrates, in marine and terrestrial environments, with everyone working together towards one goal,” says Bottjer.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- Mass extinction by 2100? Supercomputer predicts one-quarter of Earth’s species will die by century’s end

- Air pollution is a buzzkill for bugs, could lead to insect mass extinction

- Sixth mass extinction on Earth already underway, scientists say

“… our findings show that the mass [atmospheric] extinction event exerted greater pressure on the land than on the ocean…”

No shit Sherlock!

And they call this education!