WASHINGTON — A blackbird’s song at dawn may let us know that the morning is soon to arrive, but what do birds themselves dream of while asleep? Noteworthy new research from the University of Buenos Aires reports the creation of a new way to translate the vocal muscle activity of birds during sleep into synthetic songs.

For over two decades scientists have known that certain regions in birds’ brains responsible for singing while awake continue to show similar neural patterns during sleep. Up until now, the “code” revealing how that aviary neural information undergoes processing remained a mystery. In other words, it wasn’t possible to map out a pattern of nocturnal activity to song.

This latest research, published in Chaos, An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, looks to change that.

“Dreams are one of the most intimate and elusive parts of our existence,” says study author Gabriel Mindlin, who specializes in exploring the physical mechanisms of birdsong, in a media release. “Knowing that we share this with such a distant species is very moving. And the possibility of entering the mind of a dreaming bird — listening to how that dream sounds — is a temptation impossible to resist.”

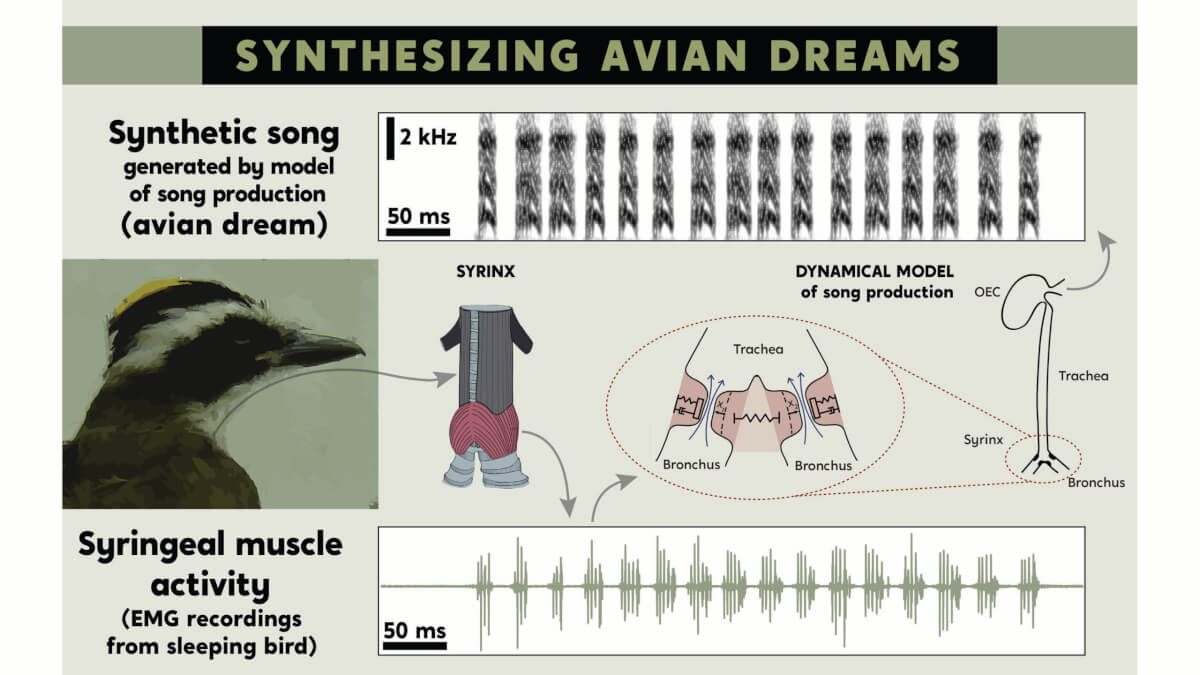

A few years ago, the same research team discovered that such patterns of neuronal activity make their way down to the syringeal muscles (a bird’s vocal apparatus). Researchers explain they can capture sleeping birds’ muscular activity data via recording electrodes, called electromyography (EMG), and then use a dynamical systems model to translate that data into synthetic songs.

“During the past 20 years, I’ve worked on the physics of birdsong and how to translate muscular information into song,” Mindlin explains. “In this way, we can use the muscle activity patterns as time-dependent parameters of a model of birdsong production and synthesize the corresponding song.”

Numerous bird species feature complex musculature. So, translating syringeal activity into song is rarely easy.

“For this initial work, we chose the Great Kiskadee, a member of the flycatcher family and a species for which we’d recently discovered its physical mechanisms of singing, and presented some simplifications,” Mindlin adds. “In other words: we chose a species for which the first step in this program was viable.”

Mindlin recalls it was incredibly moving to hear sounds emerge from the data of a bird dreaming about a territorial confrontation with a raised crest of feathers, which is a gesture that is associated with a trill used in confrontations during the day.

“I felt great empathy imagining that solitary bird recreating a territorial dispute in its dream,” he continues. “We have more in common with other species than we usually recognize.”

All in all, the new study presents biophysics as a fresh exploratory tool capable of opening the door for further quantitative studies focusing on dreams.

“We’re interested in using these syntheses, which can be implemented in real-time, to interact with a bird while it dreams,” Mindlin concludes. “And for species that learn, to address questions about the role of sleep during learning.”