BUDAPEST, Hungary — Don’t sleep on dormant volcanoes — they can still be extremely dangerous. An alarming new study reveals that even after tens of thousands of years of dormancy, a volcano can become active again, potentially posing a newfound threat to surrounding areas. This raises questions about how to explain volcanic eruptions and what factors make them more dangerous and explosive.

Scientists from ELTE Eötvös Loránd University and the HUN-REN-ELTE Volcanology Research Group, in collaboration with other European researchers, conducted the study, seeking to identify signs preceding these sudden eruptions. Their research focuses on Ciomadul, the youngest volcano in the Carpathian-Pannonian region of Romania, offering insights into volcanic hazard assessment.

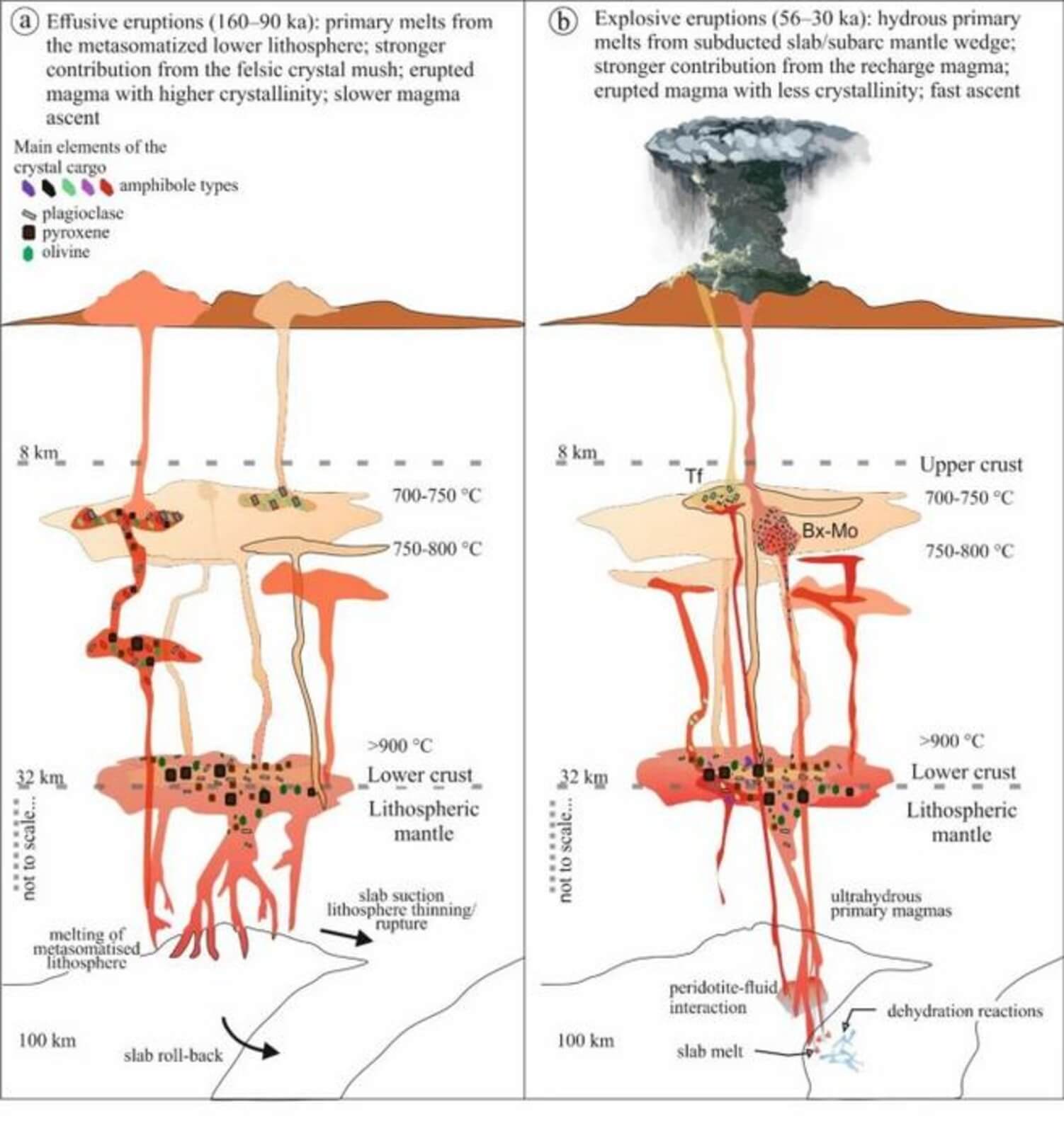

Ciomadul, a typical example of a long-dormant volcano, has experienced several periods of quiescence (inactivity) in its nearly one million-year existence. Despite tens of thousands, or even over 100,000 years of dormancy, volcanic eruptions have resumed. The most significant volcanic activity in recent history occurred in the last 160,000 years, including lava dome extrusions between 95,000 and 160,000 years ago. After over 30,000 years of dormancy, eruptions restarted 56,000 years ago, resulting in more dangerous and explosive eruptions compared to the previous active period. The volcano has been dormant again for the past 30,000 years.

“They were formed by more dangerous, explosive eruptions compared to the previous active episode,” says Barbara Cserép, a PhD student at ELTE, in a media release. “So, it is important to know what was the reason for this change in eruption style.”

The research relies on the study of rock-forming minerals to uncover the cause of volcanic eruptions and the factors controlling their style. Detailed examination of these minerals helps researchers determine magma conditions, the architecture of the magma reservoir system, and the processes leading to eruptions. One significant mineral in the study is amphibole, which can provide insights into magma conditions. Chemical variations in amphibole composition revealed differences in magma conditions, especially the influx of higher-temperature recharge magmas, which played a role in making eruptions explosive.

“Compared to the previous, lava dome-forming eruptive period, these fresh recharge magmas carried amphibole with a distinct composition, i.e. these magmas were slightly different, and this could play an important role in why the eruption became explosive,” explains Szabolcs Harangi, the leader of the research project.

The composition of the outermost rim of crystals and iron-titanium oxides offered insight into the conditions immediately preceding eruptions, indicating magma temperatures and oxidation levels.

While Ciomadul currently shows no signs of reawakening, the study emphasizes the potential for rapid reactivation in the presence of recharge by hot, hydrous magma. This research highlights the importance of quantitative volcano petrology studies in understanding volcanic hazards and better predictions of eruptions, even in long-dormant volcanoes.

“This research is novel in the sense that it is performed in a long-dormant volcano, and as a result, the Ciomadul volcano is receiving an increasing international attention,” concludes Harangi.

The study is published in the journal Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology.

This study is a FARCE. Not only is the earth more than a few thousand years old, but that fact makes the fact of the eruption of dormant volcanoes much more plausible. And it claims no recent eruptions of significance, conveniently ignoring Surtsey and Mount St. Helens, to name a couple. And the reason for ignoring the latter? Because it DISPROVES that long ages are necessary to form certain geological features considered indicative of an old earth.

Once more you show your bias for FAKE NEWS.