LA JOLLA, Calif. — Consuming alcohol only in moderation is good advice for anyone, but new research suggests those with a genetic predisposition toward dementia should be especially hesitant to hit the bottle. Scientists at Scripps Research and the University of Bologna report alcohol use disorder (AUD) quickens the progression of Alzheimer’s disease among those with a genetic susceptibility to the memory-robbing disease.

More specifically, the research team discovered that repeated alcohol intoxication has a connection to changes in gene expression indicative of disease progression within the brains of mice that are genetically predisposed to Alzheimer’s. In other words, when those rodents were drunk on a regular basis, they displayed signs of failing brain health roughly two months sooner than they normally would.

“Adding ethanol to an Alzheimer’s genetic background pushes Alzheimer’s forward by a few months or a few years,” says co-lead author Federico Manuel Giorgi, PhD, a professor of Computational Genomics at the University of Bologna, in a media release.

While few studies have explored the potential for alcohol to worsen Alzheimer’s disease, some epidemiological studies have hinted that AUD has a link to a greater dementia risk. So, in an effort to explore the potential for alcohol to trigger Alzheimer’s disease, study authors repeatedly exposed a group of rodents to levels of alcohol similar to what people drink when they have AUD over the course of several months. Additionally, they compared a control group of mice to mice carrying three genes known to increase Alzheimer’s risk.

Researchers discovered that in comparison to the healthy control mice, alcohol-exposed mice became progressively worse at learning and remembering spatial patterns, and even displayed signs of cognitive decline at an earlier age than expected.

“We started seeing cognitive impairments in the alcohol-treated mice approximately two months before they would normally develop these impairments,” adds co-lead author Pietro Paolo Sanna, MD, a professor of Immunology and Microbiology at Scripps Research.

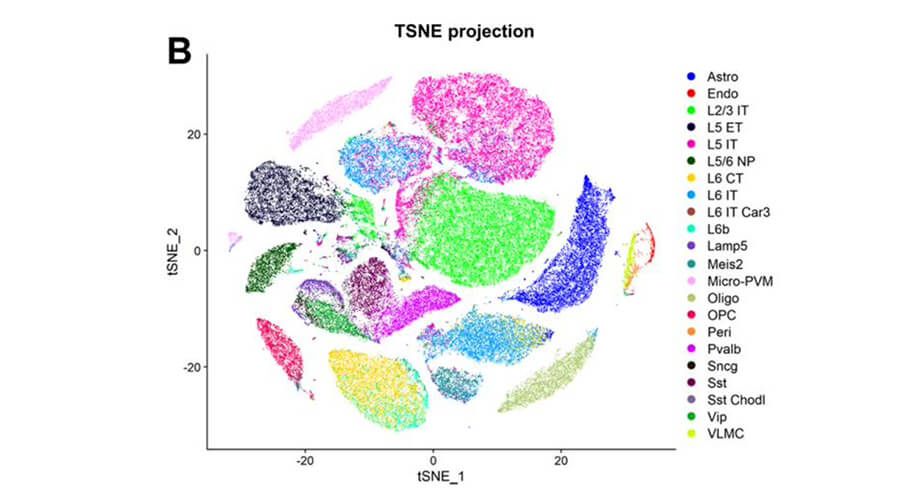

Also, in an effort to pinpoint exactly what was happening in these cells during alcohol use disorder, the research team characterized and compared the gene expression of over 100,000 individual cells collected from the brains of alcohol-exposed and unexposed mice.

This led to the discovery that alcohol exposure has an association with widespread changes in gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. Alcohol-exposed mice showed higher expression of genes associated with neuronal excitability, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Besides just occurring in neurons, these changes also took place in supporting cells such as astrocytes, microglia, and endothelial cells.

“This is interesting because it used to be thought that neurons were the ones carrying out all the responses associated with Alzheimer’s disease, and only recently have these cell types been recognized as having a role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis,” Dr. Giorgi notes.

When study authors compared the gene transcription profiles of the alcohol-exposed rodents to unexposed mice of various ages and stages of Alzheimer’s with the same genetic background, they uncovered that the gene transcription profiles of the alcohol-exposed mice much more closely resembled those of older mice dealing with more severe cognitive decline than mice their own age.

“When we compared the alcohol-exposed mice to the same type of mice with early or late progression of the disease—so mice that are not yet impaired in any way and mice that are really compromised—we found that the effect of alcohol is to move gene expression towards the advanced disease,” Dr. Sanna explains.

Study authors believe that a stronger grasp on how gene expression changes in different populations of cells during Alzheimer’s is a key step toward understanding the molecular triggers behind memory loss and developing more effective therapies. They speculate that the gene transcription pathways involved in Alzheimer’s progression with AUD may also help in explaining disease progression even in the absence of alcohol consumption.

“The mechanisms of progression that this dataset will uncover may apply to Alzheimer’s in general, even without alcohol,” Dr. Sanna concludes. “Ultimately, this gene expression analysis will identify key regulatory genes that drive Alzheimer’s progression.”

While this study focused solely on familial Alzheimer’s, researchers want to explore if alcohol consumption also impacts the onset and progression of sporadic Alzheimer’s in those who are not genetically predisposed to dementia moving forward.

The study is published in the journal eNeuro.

You might also be interested in:

- Even moderate drinking kills brain cells, increases Alzheimer’s risk

- After 20 years of research, new drug may slow progression of Alzheimer’s disease

- New Alzheimer’s gene discovered that can trigger the disease in women