ZÜRICH, Switzerland — A comprehensive analysis of 5,000-year-old metal cauldrons shows that early human families enjoyed deer stew dinners. The discovery provides essential insights into the Bronze Age diet.

Historically, archaeologists have inferred the purposes of ancient tools based on written records and contextual evidence. When delving into the dietary habits of people from millennia ago, many assumptions had to be made regarding their culinary choices and preparation methods.

This recent study conducted an analysis of protein residues found in these age-old cooking vessels. Researchers discovered that during the Maykop period, from 3700 BC to 2900 BC, inhabitants of the Caucasus consumed deer, sheep, goats, and bovine species.

“It’s really exciting to get an idea of what people were making in these cauldrons so long ago,” says Dr. Shevan Wilkin from the University of Zurich in a media release. “This is the first evidence we have of preserved proteins of a feast—it’s a big cauldron. They were obviously making large meals, not just for individual families.”

It’s widely recognized by scientists that fats preserved in ancient pottery and proteins found in dental calculus (hardened plaque on teeth) provide indications of ancient dietary habits. This innovative study integrates protein analysis with archaeology, shedding light on the specific dishes prepared in these vessels.

According to the research team, the preservation of proteins on the cauldrons is attributed to the antimicrobial properties of many metal alloys. These properties deter the microbes in soil that usually degrade proteins in materials like ceramic and stone.

“We have already established that people at the time most likely drank a soupy beer, but we did not know what was included on the main menu,” says Dr. Viktor Trifonov from the Institute for the History of Material Culture in Russia.

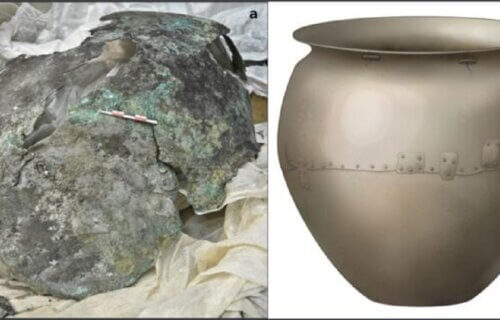

From the seven cauldrons unearthed at burial sites in the Caucasus region — spanning from southwestern Russia to Turkey and encompassing present-day Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia — the team procured eight residue samples. They successfully identified proteins associated with blood, muscle tissue, and milk.

One specific protein, heat shock protein beta-1, suggested that the cauldrons were used to cook deer or bovine meats, such as cow, yak, or water buffalo. Furthermore, the discovery of milk proteins pointed to dairy preparation, possibly from sheep or goats.

Radiocarbon dating techniques estimated the cauldrons’ usage between 3520 BC and 3350 BC, making them over 3,000 years older than any previously analyzed vessels.

“It was a tiny sample of soot from the surface of the cauldron. Maykop bronze cauldrons of the fourth millennium BC are a rare and expensive item, a hereditary symbol belonging to the social elite,” shares Dr. Trifonov.

Although the cauldrons bore evidence of use and subsequent repair, the team interpreted these signs as indicative of their value. Such items would have demanded advanced craftsmanship and might have represented significant symbols of wealth or societal standing.

“We would like to get a better idea of what people across this ancient steppe were doing and how food preparation differed from region to region and throughout time,” Dr. Wilkin elaborates. “If proteins are preserved on these vessels, there is a good chance they are preserved on a wide range of other prehistoric metal artifacts. We still have a lot to learn, but this opens up the field in a really dramatic way.”

The study is published in the journal iScience.

South West News Service writer James Gamble contributed to this report.

You might also be interested in:

- 3,500 years ago, wealthy people had access to primitive brain surgery!

- Ancient toilet reveals elite residents in Jerusalem dealt with life-long intestinal diseases

- Archaic Campbell’s: Ancient humans stored bone marrow like canned goods, study finds

Love # 5 can’t find it or the powder. Anyone have info?