LANCASHIRE, United Kingdom — Flat Earthers might want to hitch their wagon to Jupiter. In a revelation that challenges our long-standing knowledge of the cosmos, researchers from the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) have discovered that large planets like Jupiter that form far away from their host stars were initially flat like smarties rather than their current spherical shape. So, does this mean this often-mocked group was right all along? The answer is a definite — maybe?

This revolutionary research, spearheaded by the Jeremiah Horrocks Institute for Mathematics, Physics, and Astronomy at UCLan, utilizes advanced computer simulations to shed light on the earliest stages of planetary formation.

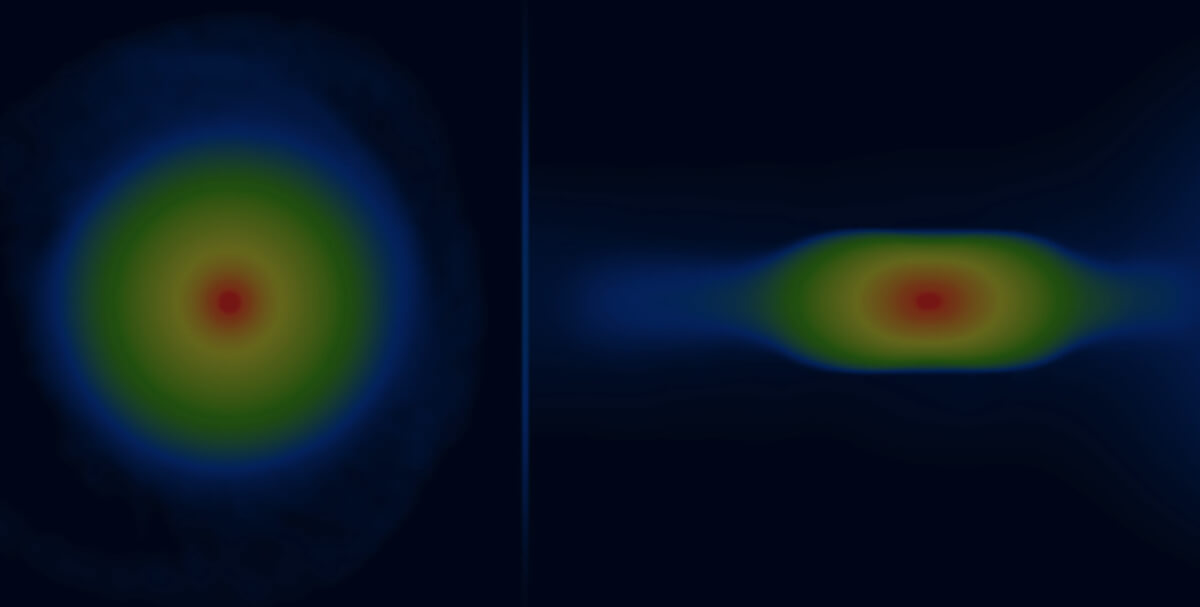

Astrophysicists have traditionally believed that planets, from their inception, take on a spherical form. However, the UCLan team’s findings suggest that protoplanets — nascent planets recently formed around stars — are actually oblate spheroids, a shape that is more flattened than round. This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of how planets form and the dynamic processes that take place in the early life of a new world.

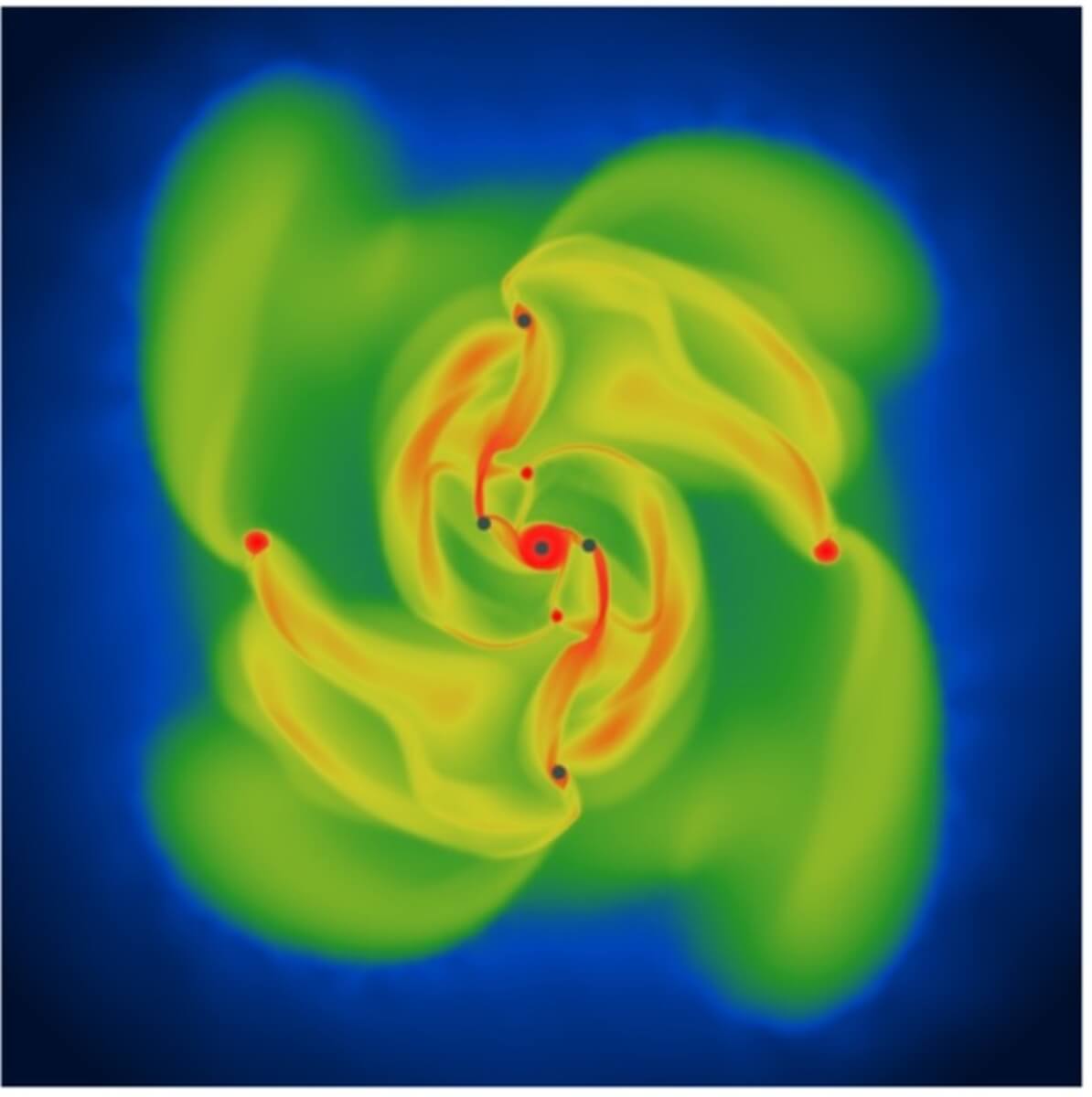

Scientists employed computer simulations based on the theory of disc-instability, which posits that protoplanets emerge quickly from the fragmentation of large, rotating discs of dense gas orbiting young stars. This theory contrasts with the core accretion model, which argues for a gradual accumulation of dust particles over much longer periods. The disc-instability model is particularly intriguing because it can account for the rapid formation of large planets at substantial distances from their host stars, offering an explanation for some of the exoplanets observed by astronomers.

“Many exoplanets, which are planets that orbit stars in other solar systems outside of our own, have been discovered in the last three decades. Despite observing many thousands of them, how they form remains unexplained,” says study lead author Dr. Adam Fenton, who recently completed his doctorate at UCLan, in a media release.

The study required over half a million CPU hours on the UK’s DiRAC High Performance Computing Facility. Dr. Fenton further highlighted the significance of their findings, noting the remarkable results that challenge previous assumptions about planetary shapes.

“This theory is appealing due to the fact that large planets can form very quickly at large distances from their host star, explaining some exoplanet observations,” explains Dr. Fenton.

“We have been studying planet formation for a long time but never before had we thought to check the shape of the planets as they form in the simulations. We had always assumed that they were spherical,” adds Dr. Dimitris Stamatellos, a co-investigator and reader in astrophysics at UCLan. “We were very surprised that they turned out to be oblate spheroids, pretty similar to smarties!”

Researchers also uncovered that the growth of these new planets predominantly occurs as material falls onto them from their poles rather than their equators, further challenging previous conceptions. This finding has significant implications for observing young planets through telescopes, as the appearance of these planets may vary depending on the angle of observation.

Such discoveries are critical for unraveling the mysteries of planet formation, with potential observational confirmation from advanced telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, and the Very Large Telescope. The UCLan team is continuing their research with more sophisticated computational models to explore how the environment influences the shape of these planets and to predict their chemical compositions for future observational verification.

The study is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters.

You might also be interested in:

- The Sun once had rings just like Saturn, study reveals

- Earthshaking Discovery: Tectonic Plates Not The Driving Force That Formed Continents

- Believing in conspiracy theories more common among insecure and paranoid personalities

- Best Of The Best Telescopes For Beginners In 2023: Top 5 Stargazers Most Recommended By Experts

No, flat earthers were never and are never right. The earth may have been flat as a pancake in the beginning but it isn’t now. Flat earthers insist the earth is flat now, like today, which it obviously isn’t. Now some fools are going to read this headline, but not the article, and think the earth is really flat. 😂

Food for the annoying flatheads and their sub-80 IQ’s. But we all know simulations are just that… simulations, and nothing more. Feed a computer simulation what it needs to give you a pancake and all you need to do is reach for the syrup and a fork.

LIKE ALL THE c o v i d STIMULATIONS , ALL WRONG