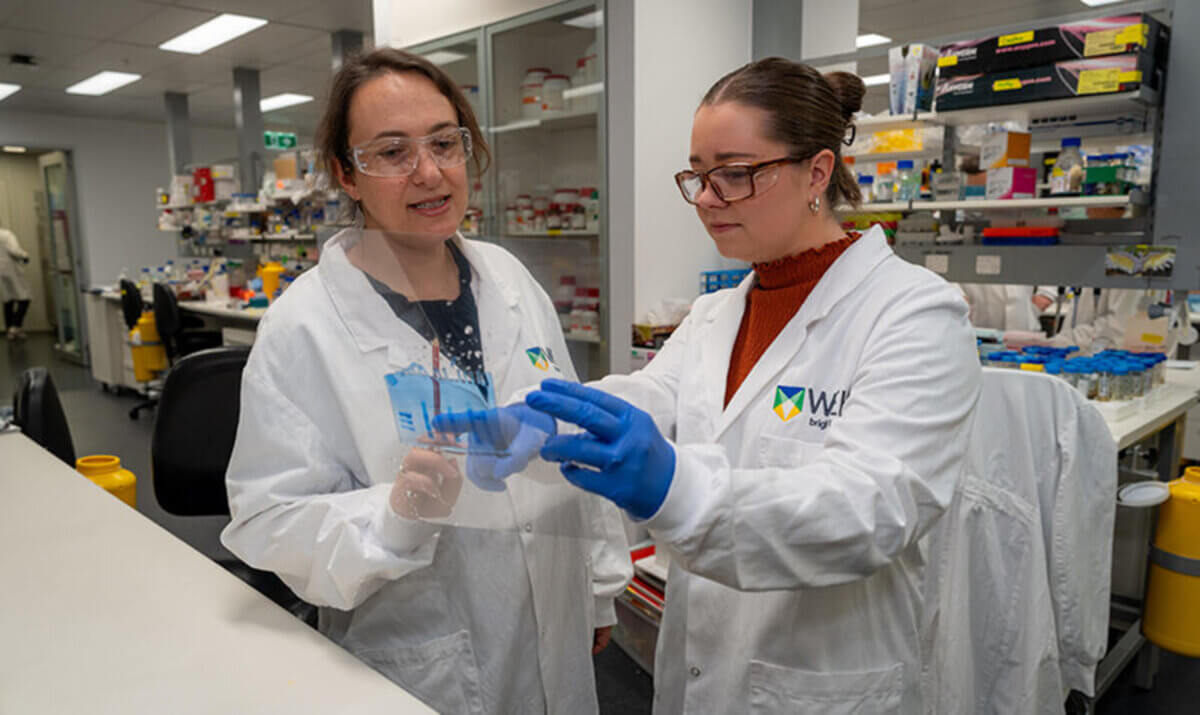

PARKVILLE, Australia — Millions across the globe carry an inflammation-causing gene linked to “explosive” cell death. A new study led by a team at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) in Australia has discovered that up to three percent of the world’s population carries a genetic variation that amplifies their risk of inflammation due to an intense form of cell death known as “necroptosis.”

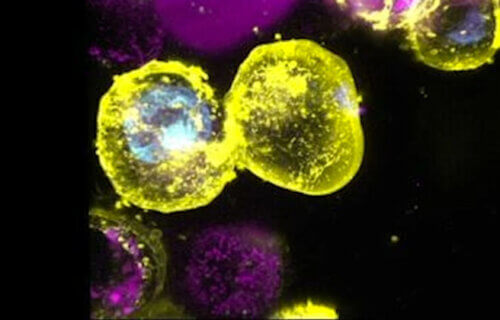

This might shed light on why some individuals are more susceptible to conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or suffer severe reactions when infected by bacteria, including salmonella. Our bodies naturally eliminate millions of cells every minute, a process vital to our health. This cell death acts as a defense mechanism, getting rid of malfunctioning or harmful cells. It also halts the spread of viruses, bacteria, and even cancer.

“This is a good thing in the case of a viral infection, where necroptosis not only kills the infected cells but instructs the immune system to respond, clean things up, and start a more specific, long lived immune response,” says study first author Dr. Sarah Garnish in a media release. “But when necroptosis is uncontrolled or excessive, the inflammatory response can actually trigger disease.”

A critical player in controlling necroptosis is the gene named MLKL. Under normal circumstances, this gene remains dormant, held in check by the cell’s “brakes.” However, some individuals possess a version of MLKL with weak brakes.

“For most of us, MLKL will stop when the body tells it to stop, but 2 to 3 percent of people have a form of MLKL that is less responsive to stop signals,” explains Dr. Garnish. “While 2 to 3 percent doesn’t seem like much, when you consider the global population, this adds up to many millions of people carrying a copy of this gene variant.”

Dr. Joanne Hildebrand, the project leader, says this genetic change is part of a bigger picture termed “polygenic risk.” Here, multiple genes and environmental factors (like diet or smoking habits) collectively influence an individual’s vulnerability to a disease.

“Taking Type 2 diabetes as an example, it’s rare that just one gene change determines whether someone will develop the condition,” says Dr. Hildebrand. “Instead many different genes play a role, as do environmental factors, like diet and smoking.”

However, directly linking this MLKL variation to a specific disease isn’t straightforward.

“We haven’t tagged this MLKL gene variant to any one particular disease yet, but we see real potential for it to combine with other gene variants, and other environmental cues, to influence the intensity of our inflammatory response,” says Dr. Hildebrand.

The research’s implications are vast in the realm of personalized medicine. The decreasing cost of genome sequencing means scientists can now link common genetic variations with diseases more efficiently. Future research might even determine if someone is predisposed to a severe case of ailments like COVID-19 or how they might respond to treatments like chemotherapy.

“Every piece of information like this helps us make personalized medicine more of a reality,” says Dr. Garnish.

The team is also exploring whether unchecked necroptosis could have benefits, like providing a robust defense against specific viruses.

“Gene changes like this don’t usually accumulate in the population over time unless there is a reason for it – they generally get passed on because they do something good,” notes Dr. Garnish. “We’re looking at the downsides of having this gene change, but we’re looking for the upsides as well.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

You might also be interested in:

- High cholesterol fuels cancer growth, makes disease impervious to cell death

- A single genetic mutation may be protecting people who get COVID without symptoms

- Primate DNA helps scientists close in on origin of modern disease mutations