🔑 Key Findings:

- Glitter polluting oceans and rivers is blocking out sunlight underwater.

- Photosynthesis rates were significantly higher in cleaner bodies of water.

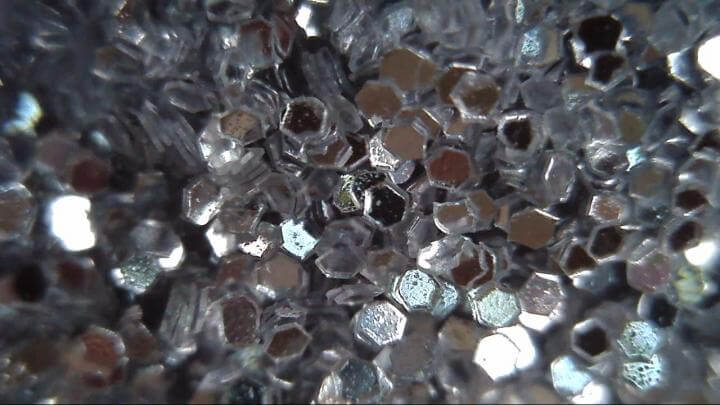

- The problem stems from metals like aluminum in glitter.

SÃO PAULO, Brazil — It might be time to put down the glitter and find a new way to sparkle. Researchers at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) in Brazil found a hazard posed by glitter: its detrimental effect on aquatic life.

Glitter, a common embellishment in apparel, makeup, and holiday decorations, is known for its brilliant shine. However, its environmental footprint is far from glamorous. Classified as an emerging pollutant, glitter contributes to the microplastics (tiny plastic fragments less than 5 millimeters in length) that evade wastewater treatment and pollute rivers and oceans. These microplastics interfere with the well-being of aquatic organisms in various ways.

The UFSCar study uncovers an additional threat. Beyond its plastic composition, glitter contains metals, such as aluminum, which can block sunlight underwater, impeding the photosynthesis and growth of aquatic plants.

The research focused on the Large-flowered waterweed (Egeria densa), an aquatic plant native to Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Macrophytes, like E. densa, are crucial for aquatic ecosystems, providing food, shelter, oxygen, and serving in biofiltration projects to cleanse water bodies. These plants are also popular in aquariums and artificial lakes for their oxygenating and aesthetic benefits.

Using laboratory experiments, the team studied the impact of glitter on E. densa. The plants were incubated in water mixed with common retail glitter, comparing their photosynthesis rates under various conditions: with and without glitter, and in the presence and absence of light.

The findings were telling. Photosynthesis rates in E. densa were 1.54 times higher without the presence of glitter. The microplastic particles diminished light availability in the water, affecting the plants’ ability to photosynthesize and respire.

“These findings support the hypothesis we began with, which was that glitter interferes with photosynthesis, possibly owing to the reflection of light by the microplastic particles’ metallic surface,” says study first author Luana Lume Yoshida, a master’s degree student in ecology and natural resources at UFSCar, in a media release.

The study emphasizes the ecological implications of glitter pollution. Not only does it physically interfere with specific aquatic species, but it also contributes to broader ecosystem disruptions and affects the food chain.

“In this experiment, we specifically observed the physical interference of glitter in a species of macrophyte, but there are better-known references in the scientific literature to water contamination and consumption of these particles by other aquatic organisms,” notes study last author Marcela Bianchessi da Cunha-Santino, principal investigator in the Bioassay and Mathematical Modeling Laboratory (LBMM) in UFSCar’s Department of Hydrobiology.

The findings prompt a call for more sustainable practices, particularly during celebratory events like Carnival, where glitter use is rampant. The study suggests that public policies should encourage the adoption of eco-friendly alternatives to mitigate these environmental impacts.

“With a robust ‘database’, we’ll be able to think about public policy to foster more conscious consumption of this type of material, but for now it’s important to warn society that changes in photosynthesis rates, however remote they may seem from our lives, are linked to other changes that affect us more directly, such as the decrease in primary production by food chains in aquatic environments [i.e. organisms at the bottom of the food chain]. If there are more sustainable alternatives to glitter, why not switch to these right away?” says study co-author Irineu Bianchini Jr., a principal investigator at LBMM.

The study is published in the New Zealand Journal of Botany.