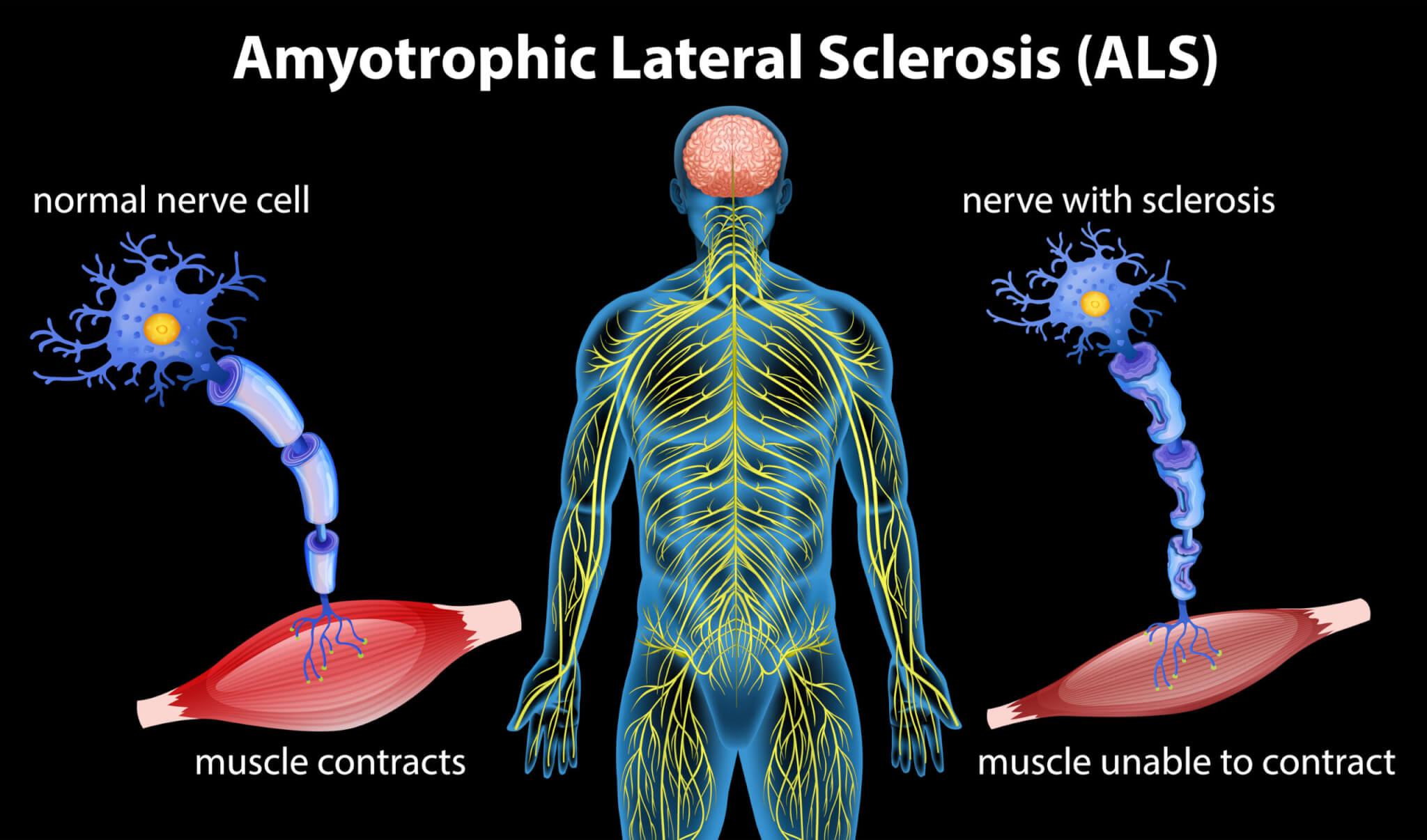

PORTLAND, Ore. — Researchers from Oregon Health and Science University are one step closer to finding a cure for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Their study is the first to modulate an immune system-related protein to slow down the progress of ALS, a fatal neurodegenerative disease also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease in the United States.

The study used a mouse model and then confirmed the work in donated human brain tissue from patients diagnosed with ALS. Previously, studies have suggested that immune cells play a role in ALS, but this time researchers went a little deeper and utilized a high-throughput screening technique to identify a specific protein called alpha-5 integrin. The protein is expressed in immune cells within the brain and spinal cord of people with this condition.

“When we blocked its expression in mice, we were able to slow down the disease,” says senior author Bahareh Ajami, Ph.D., assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology and behavioral neuroscience in the OHSU School of Medicine, in a university release. “We hope that it will get to the clinic very soon.”

The team used a monoclonal antibody targeting a5 integrin, which had already been developed and used in the treatment of certain cancers. Therefore, it has already gone through extensive safety studies in order to gain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

“Hopefully, it could be repurposed,” Dr. Ajami adds.

Using the human tissue from 139 donated brains, the researchers were able to confirm that a5 integrin was present in parts of the brain linked to motor function. Specifically, they found that the protein was highly expressed by microglial cells and macrophages in blood within the spinal cord, motor cortex, and peripheral nerves affected by ALS. These cells are heavily associated with the immune system.

The team then tested the monoclonal antibody in mice genetically predisposed to develop ALS, finding that it preserved motor function and slowed disease progression, which positively impacted survival rates.

“We couldn’t believe they were doing so much better,” Ajami says.

Ajami’s lab primarily explores immune system modulation to treat neurodegenerative conditions, and she says that this study shows potential for applying immunotherapies to ALS, given that the treatment is already used against cancer. Monoclonal antibodies are already being used against Alzheimer’s disease.

“At this point, we cannot say it’s a cure but it’s a very interesting start,” Ajami explains. “It may be similar to what immunotherapy did for cancer or will do for Alzheimer’s by targeting immune cells.”

The next step for this research involves developing dose-response studies using the mouse model and going from there in order to hopefully see people with ALS being treated using this modality.

The findings are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- One special probiotic may be key to preventing brain degeneration, curing ALS

- Lab-grown ‘mini-brains’ open door to better treatments for dementia, ALS

- Chemo, Immunotherapy Combo May Be Effective Mesothelioma Treatment