CHICAGO — Today’s governments might be able to draw inspiration from the ancient Maya when it comes to addressing water treatment challenges in the age of global warming, a new study explains. The water purification methods practiced by the Mesoamerican civilization — dating back as far as 4,000 years ago — offer a cost-effective and sustainable alternative to modern water treatment techniques, researchers argue.

The Maya were pioneers in creating methodologies to purify, filter, and store water. They built reservoirs that were naturally cleansed by aquatic plants and specific sands. Researchers now propose that merging contemporary knowledge with the insights of the ancient Maya could lead to economical and efficient water treatment solutions.

The Mayan civilization has had a continuous presence in present-day nations of Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras for at least 3,800 years. They were groundbreaking in their development of positional numerals, including the concept of zero. Furthermore, Mesoamerica was one of the few regions globally to originate writing. The Maya deciphered time intricacies through their comprehensive Long Count calendar, showcasing their advanced arithmetic skills.

Innovatively, they adopted intense farming in swamps, utilizing a method called “raised fields.” This involved creating canal and ditch networks to manage water during both the rainy and annual five-month dry seasons.

The Maya built and maintained reservoirs that supplied potable water for over a millennium. These reservoirs catered to the vast populations in their magnificent cities. This sophisticated civilization developed infrastructure such as canals, dams, sluices, and berms to manage water effectively.

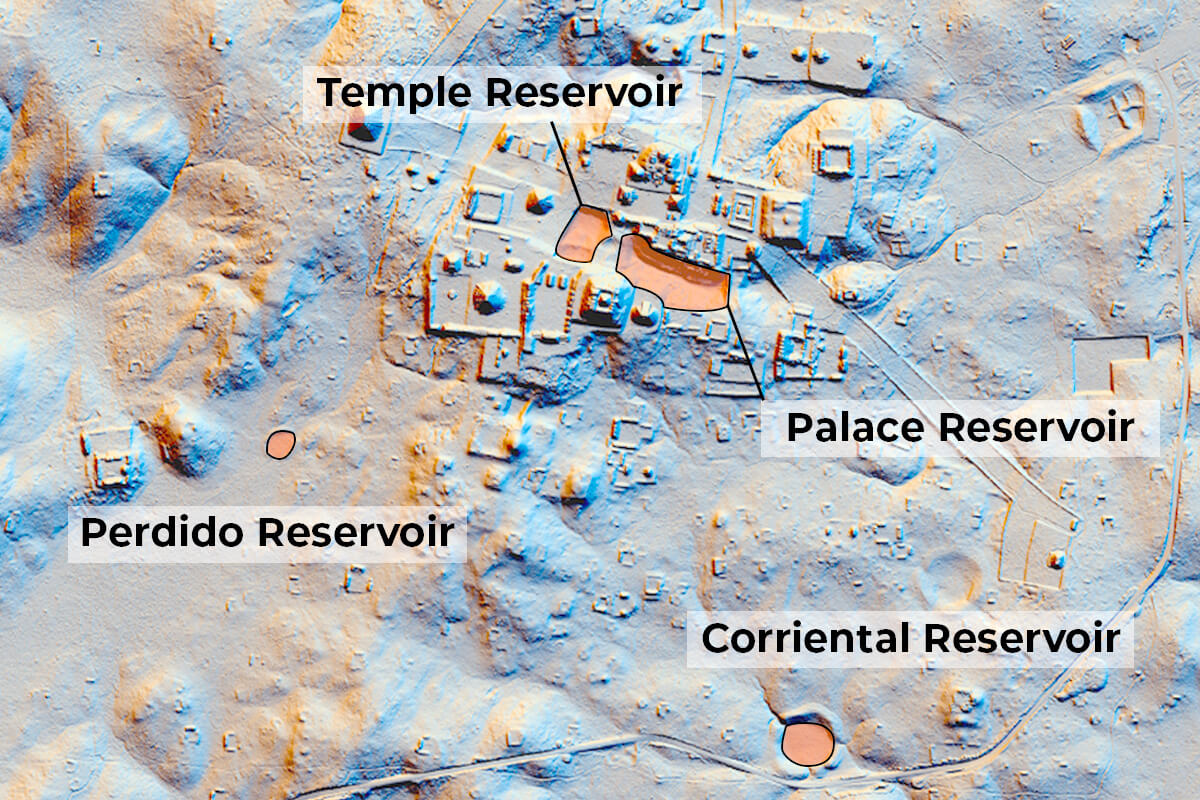

They utilized quartz sand, sometimes sourced from remote locations, to filter water in sprawling cities like Tikal, a prominent Mayan city during the Late Classic Period (600-900 AD) located in present-day northern Guatemala.

An analysis of sediment cores from a Tikal reservoir revealed the use of zeolite sand, a volcanic variant known for its ability to filter contaminants and harmful microbes. This sand was imported from locations approximately 18 miles away.

The researchers note that Tikal’s reservoirs could store over 900,000 cubic meters of water. This reservoir sustained the city’s estimated 80,000 inhabitants and their crops during dry spells.

“Most major southern lowland Maya cities emerged in areas that lacked surface water but had great agricultural soils,” says the study’s lead author Lisa Lucero, an anthropology professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago, in a media release. “They compensated by constructing reservoir systems that started small and grew in size and complexity.”

Mayan monarchs derived much of their prestige from their capacity to ensure water supply and bountiful harvests, often performing rituals to appease the rain deity, Chahk. The scientists highlight the close connection between clean water access and political authority, noting that the most extensive reservoirs were strategically placed near palatial and sacred sites.

One challenge faced by rulers was keeping reservoir water fresh. To address this, the Maya likely harnessed the filtering capabilities of aquatic plants native to Central American wetlands, including cattails, sedges, and reeds. Some of these plants have been identified in sediment cores from Maya reservoirs.

According to Prof. Lucero, these plants effectively clarified the water, reducing murkiness while absorbing contaminants. The reservoirs would undergo regular maintenance, replacing old plants with new ones, and the harvested nutrient-rich plants and soil would be repurposed as fertilizers.

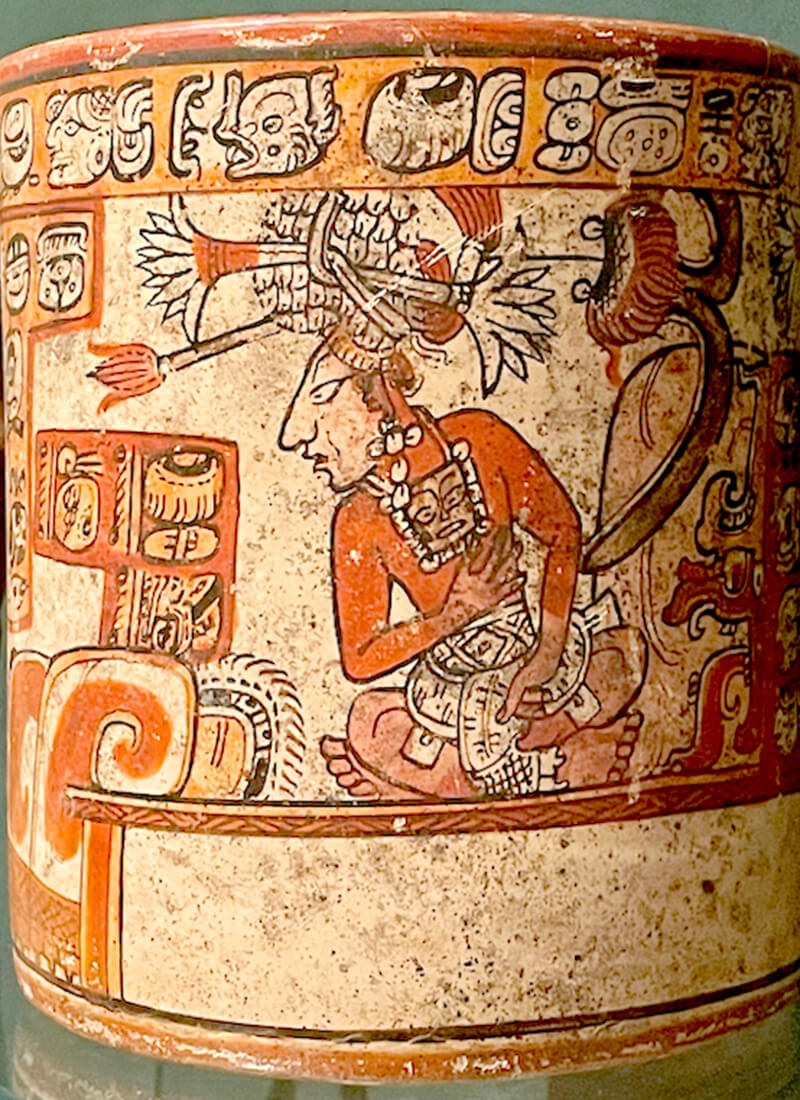

The water lily, symbolic of purity and Maya royalty, was a staple in these reservoirs. Pollen traces of this plant have been discovered in sediment cores from various reservoirs. To support water lilies, reservoirs were lined with clay, facilitating root growth. Moreover, surrounding trees and shrubs shaded the water, cooling it and preventing algae proliferation.

“The kings even donned headdresses adorned with the flowers and are depicted with water lilies in Maya art,” notes Prof. Lucero.

Evidence from various cities suggests that these reservoirs consistently supplied clean water to thousands for over a millennium, only failing during severe droughts between 800 and 900 AD.

The research team believes that as our planet grapples with changing climate patterns, we should consider adopting the aquatic plant-based techniques used by the ancient Maya. This approach not only ensures clean water but also supports aquatic life and replenishes soil nutrients.

“Constructed wetlands provide many advantages over conventional wastewater treatment systems,” Prof. Lucero stated. “They provide an economical, low technology, less expensive and high energy-saving treatment technology. The next step moving forward is to combine our respective expertise and implement the lessons embodied in ancient Maya reservoirs in conjunction with what is currently known about constructed wetlands.”

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You might also be interested in:

- Best Places To Stay In Mexico: Top 5 Resorts, Recommended By Experts

- Best Water Filters: Top 5 Purifiers For Clean H2O, According To Experts

- Non-toxic powder powered by the Sun zaps bacteria out of contaminated water

- Ancient pathogens released from melting ice could wreak havoc on the world, new analysis reveals

South West News Service writer James Gamble contributed to this report.