COLUMBIA, S.C. — Not only is the Mona Lisa a priceless piece of art, but thanks to her hands, it’s now helping to treat high cholesterol! In Leonardo da Vinci’s classic painting, Mona Lisa’s hands reveal signs of a condition called xanthomas, hinting at the presence of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).

This genetic disorder, which affects about 1 in 200 adults, according to the American Heart Association, causes elevated bad cholesterol levels in the blood, putting individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease.

FH is tied to a mutation in the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), which normally assists in regulating cholesterol. This mutation hinders the liver’s ability to manage cholesterol levels, leading to elevated cholesterol in the bloodstream. While statins, which increase LDLR levels, are typically prescribed to treat high cholesterol, they aren’t effective for all, especially those with specific FH mutations.

However, researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) have made a breakthrough by screening compounds that might decrease the secretion of apolipoprotein B (apoB) – a major LDL particle protein – from liver cells. By testing the South Carolina Compound Collection, a set of around 130,000 compounds, they identified a group of molecules that decreased both apoB secretion and cholesterol levels. These findings could pave the way for new FH treatments.

“Our approach is the original way of doing pharmacology – trying to find drugs that can fix the disease without knowing how it fixes it,” says Stephen Duncan, D.Phil., professor and SmartState Endowed Chair in the Department of Regenerative Medicine and Cell Biology at MUSC, in a media release. “You model the disease, and then you can screen drugs to find out which ones work. Then you can work out retrospectively how the drug functions.”

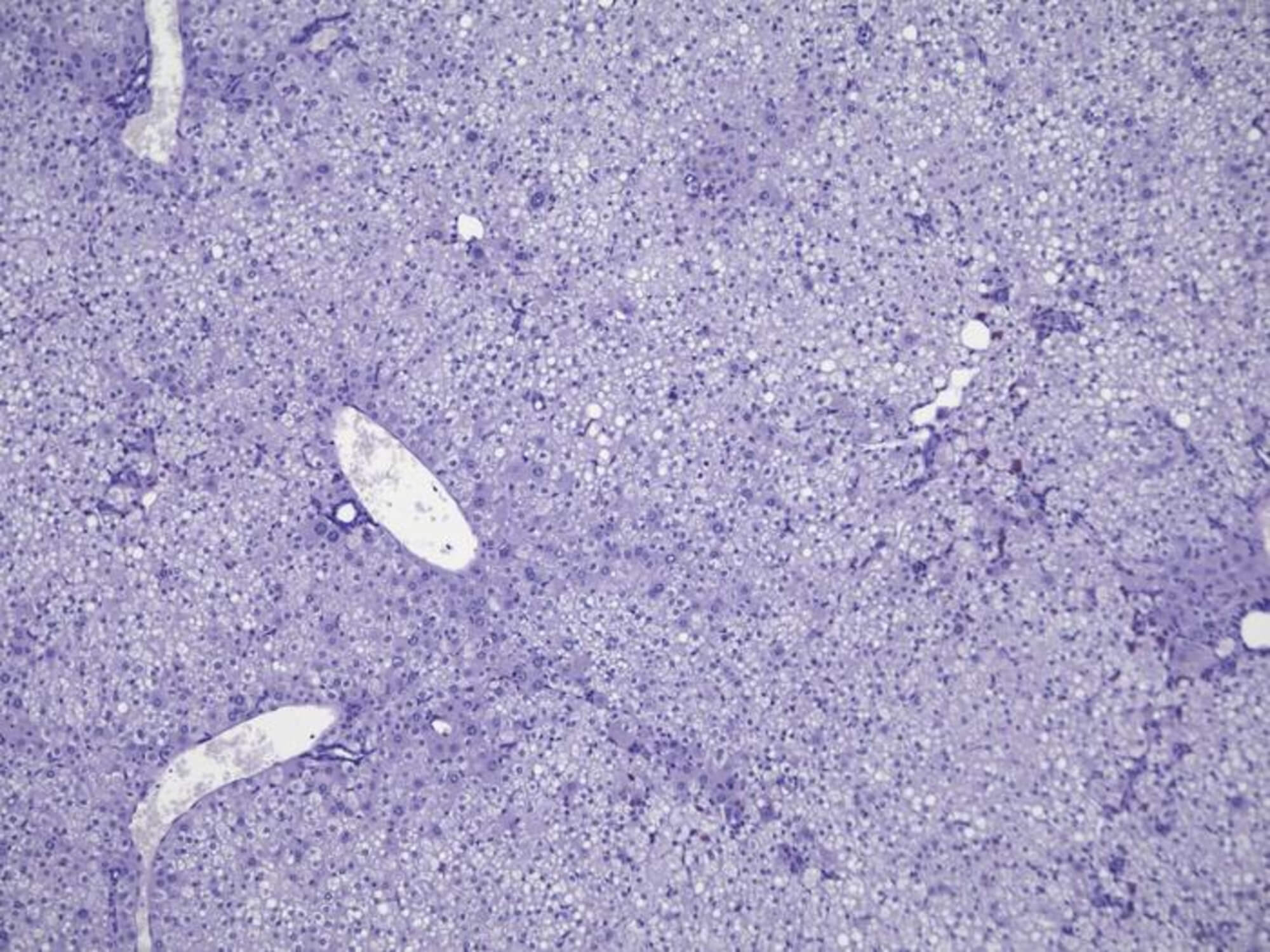

The team produced human liver-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) – stem cells derived from skin or blood. This technique enabled the scientists to test a vast number of chemical compounds, leading to the discovery of a unique compound class that might treat FH.

Upon testing these compounds on mice, though, they proved ineffective. A closer look revealed mouse liver cells were resistant to the compounds. To address this, researchers used Avatar mice – mice with livers made from human cells. This model allowed the compounds to work effectively.

“Showing that you can use these human stem cells as a system to model disease, complete a drug discovery process and find a drug that could potentially be used to treat a patient – that is the epitome of personalized medicine,” says Duncan. “This shows there is a very feasible way to do drug discovery using a human system.”

While the findings are promising, there’s more research ahead.

“Finding what the drug target is and showing the mechanism of action is an absolute a priority,” notes Duncan.

The study is published in the journal Communications Biology.