CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Flossing isn’t everyone’s idea of a fun activity, but researchers from the Forsyth Institute are highlighting the hidden dangers of plaque — both in the mouth and the brain. Scientists have uncovered a link connecting periodontal (gum) disease with the formation of amyloid plaque, considered a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Put another way, allowing plaque to buildup on your teeth may result in a different type of plaque invading your mind.

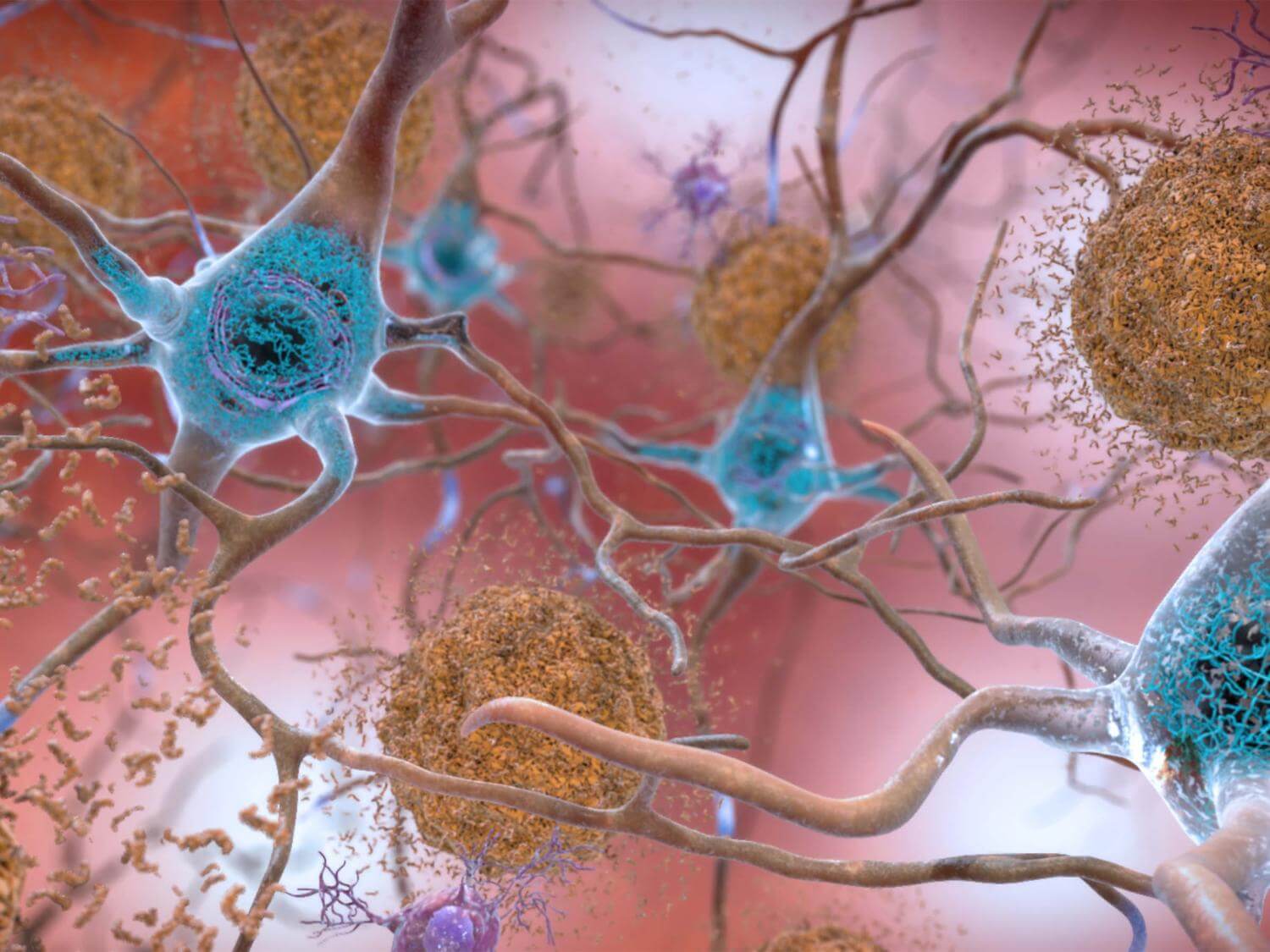

Researchers found that oral bacteria can actually travel from the mouth to the brain, causing brain cells to become dysfunctional and promoting neuroinflammation. In collaboration with researchers from Boston University, the team at the Forsyth Institute successfully demonstrated that gum disease can indeed lead to changes in brain cells called microglial cells. These cells are responsible for defending the mind from amyloid plaque.

Amyloid plaque is a type of protein that is closely linked with both cell death in general, and cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer’s. This latest work provides important insight into how oral bacteria makes its way to the brain, and the role neuroinflammation plays in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We knew from one of our previous studies that inflammation associated with gum disease activates an inflammatory response in the brain,” says Dr. Alpdogan Kantarci, senior member of staff at Forsyth and a senior author of the study, in a media release. “In this study, we were asking the question, can oral bacteria cause a change in the brain cells?”

The microglial cells studied by the research team are a specific type of white blood cell responsible for the digestion of amyloid plaque. Study authors discovered that, when exposed to oral bacteria, the microglial cells tend to overstimulate and eat too much.

“They basically became obese” Dr. Kantarci explains. “They no longer could digest plaque formations.”

This observation is significant because it shows the impact of gum disease on systemic health. Gum disease can cause lesions to develop between one’s gums and teeth. The area of such lesions is usually about the size of a palm.

“It’s an open wound that allows the bacteria in your mouth to enter your bloodstream and circulate to other parts of your body,” Dr. Kantarci adds.

The bacteria is capable of passing through the blood-brain barrier and stimulating the microglial cells in the brain. Researchers used mouse oral bacteria to induce gum disease among a group of lab mice, allowing them to track periodontal disease progression in the rodents and eventually confirm that the bacteria had traveled to the brain.

Next, the microglial cells were isolated and exposed to the oral bacteria. This exposure stimulated the microglial cells, activating neuroinflammation and changing how microglial cells deal with amyloid plaques.

“Recognizing how oral bacteria causes neuroinflammation will help us to develop much more targeted strategies,” Dr. Kantarci concludes. “This study suggests that in order to prevent neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, it will be critical to control the oral inflammation associated with periodontal disease. The mouth is part of the body and if you don’t take care of oral inflammation and infection, you cannot really prevent systemic diseases, like Alzheimer’s, in a reproducible way.”

This project marks the first time ever that scientists have caused periodontal disease with mouse-specific bacteria, allowing them to study the effects of same-species oral microbiome on the brain. Study authors say these breakthroughs bring their work closer to replicating what this process is like in humans.

The study is published in the Journal of Neuroinflammation.

You might also be interested in:

- What is Leqembi? Here’s why the FDA just approved this drug as an Alzheimer’s treatment

- Brushing, flossing helps prevent AFib: Scientists link gum disease to irregular heartbeat

- Brushing your teeth keeps your brain from shrinking, reduces risk of dementia

Whenever you see the words ‘could’ or ‘may’ it’s not ‘proven.’ My mom had absolutely horrendous teeth for years before she passed. She was totally with it until the end. So it may be a genetic favorability. Proof?