DARLINGHURST, Australia — A “lost world” of prehistoric rainforest animals is reshaping how scientists look at the Australian outback. Researchers from the Australian Museum and University of New South Wales have discovered a fossilized forest that contains thousands of pristine specimens, including insects, spiders, fish, and birds.

Some of the fossils even had remnants of their last meal still in their stomachs. Others were covered in pollen, revealing the flowers they fed on. This incredible array of creatures dates back between 11 and 16 million years, opening a window in time to what was once a thriving landscape.

Rewriting Australia’s climate history

Australia is the driest inhabited continent, with arid or semi-arid land covering 70 percent of the country. The graveyard, named McGraths Flat, is one of the most important discoveries of its kind. Study authors add that their findings reveal the historical impact of climate change and may have implications for the planet today.

“The fossils we have found prove that the area was once a temperate, mesic rainforest and that life was rich and abundant here in the Central Tablelands, NSW (New South Wales),” says lead author and paleontologist Dr. Matthew McCurry in a media release. “Many of the fossils that we are finding are new to science and include trapdoor spiders, giant cicadas, wasps and a variety of fish.”

Cicadas are among the planet’s oldest insects. The large, winged insects with bulbous eyes spend most of their time in the soil. They feed on tree roots. While they stay underground, the bugs are not hibernating. They molt four times before ever getting to the surface.

“Until now it has been difficult to tell what these ancient ecosystems were like, but the level of preservation at this new fossil site means that even small fragile organisms like insects turned into well-preserved fossils,” Dr. McCurry says.

Looking at fossils on a cellular level

Researchers add the study shows there was once life in what is now the “dead heart” of Australia. The fossil site is located in Central Tablelands, New South Wales, near the 19th century gold rush town of Gulgong. Scientists classify this area as a “Lagerstatte” — German for fossils of exceptional quality that sometimes include soft tissue.

An expedition of scientists has been secretly excavating it for the last three years. They also recovered remains of beetles, flies, algae, fungi, and other living things from a warm period in history called the Miocene Epoch.

“Using electron microscopy, I can image individual cells of plants and animals and sometimes even very small subcellular structures,” co-author Professor Michael Frese from the University of Canberra explains.

“The fossils also preserve evidence of interactions between species. For instance, we have fish stomach contents preserved in the fish, meaning that we can figure out what they were eating. We have also found examples of pollen preserved on the bodies of insects so we can tell which species were pollinating which plants.”

Dr. Frese was able to identify skin cells known as melanosomes, tiny packages of pigment inside feathers and hair.

“The discovery of melanosomes (subcellular organelles that store the melanin pigment) allows us to reconstruct the color pattern of birds and fishes that once lived at McGraths Flat. Interestingly, the color itself is not preserved, but by comparing the size, shape and stacking pattern of the melanosomes in our fossils with melanosomes in extant specimens, we can often reconstruct color and/or color patterns,” Frese adds.

McGraths Flat already drying out millions of years ago?

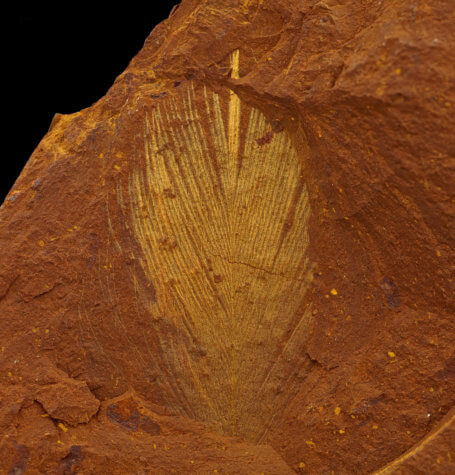

The fossils were found within an iron-rich rock called “goethite,” which is not usually a reliable source of exceptional fossils.

“We think that the process that turned these organisms into fossils is key to why they are so well preserved. Our analyses suggest that the fossils formed when iron-rich groundwaters drained into a billabong, and that a precipitation of iron minerals encased organisms that were living in or fell into the water,” Dr. McCurry continues.

A billabong – an Aboriginal word – is a calm, isolated stretch of water left behind when a river changes its course. The plants and animals described in the journal Science Advances are similar to those found in rainforests of northern Australia. However, there are signs the ecosystem at McGraths Flat was already beginning to dry during this period.

“The pollen we found in the sediment suggests that there might have been drier habitats surrounding the wetter rainforest, indicating a change to drier conditions,” McCurry says.

Australia’s wild ride through history

Study authors believe the Miocene Epoch was a time of immense change. The Australian continent separated from Antarctica and South America and started drifting northwards. When the Miocene began 23 million years ago, there was enormous richness of plant and animal life. About nine million years later, however, there was an abrupt change in climate and Australia began turning into vast shrublands and deserts. The sheer scale and variety of fossils provides unprecedented insights into the land’s mysterious past.

“The McGraths Flat plant fossils give us a window into the vegetation and ecosystems of a warmer world, one that we are likely to experience in the future. The preservation of the plant fossils is unique and provides important insights into a time period for which the fossil record in Australia is rather poor,” adds Professor David Cantrill, executive director of science at Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria.

“Australia is the most unique continent biologically, and this site is extremely valuable in what it tells us about the evolutionary history of this part of the world. It provides further evidence of changing climates and helps fill the gaps in our knowledge of that time and region,” concludes Prof. Kristofer Helgen, chief scientist at the Australian Museum, New South Wales.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.