COLLEGE PARK, Md. — A new study is warning that the planet’s growing appetite for salt is causing severe environmental and health repercussions. University of Maryland researchers are highlighting how human activities are contributing to elevated salt levels in Earth’s air, soil, and freshwater, potentially posing an “existential threat” if current trends persist.

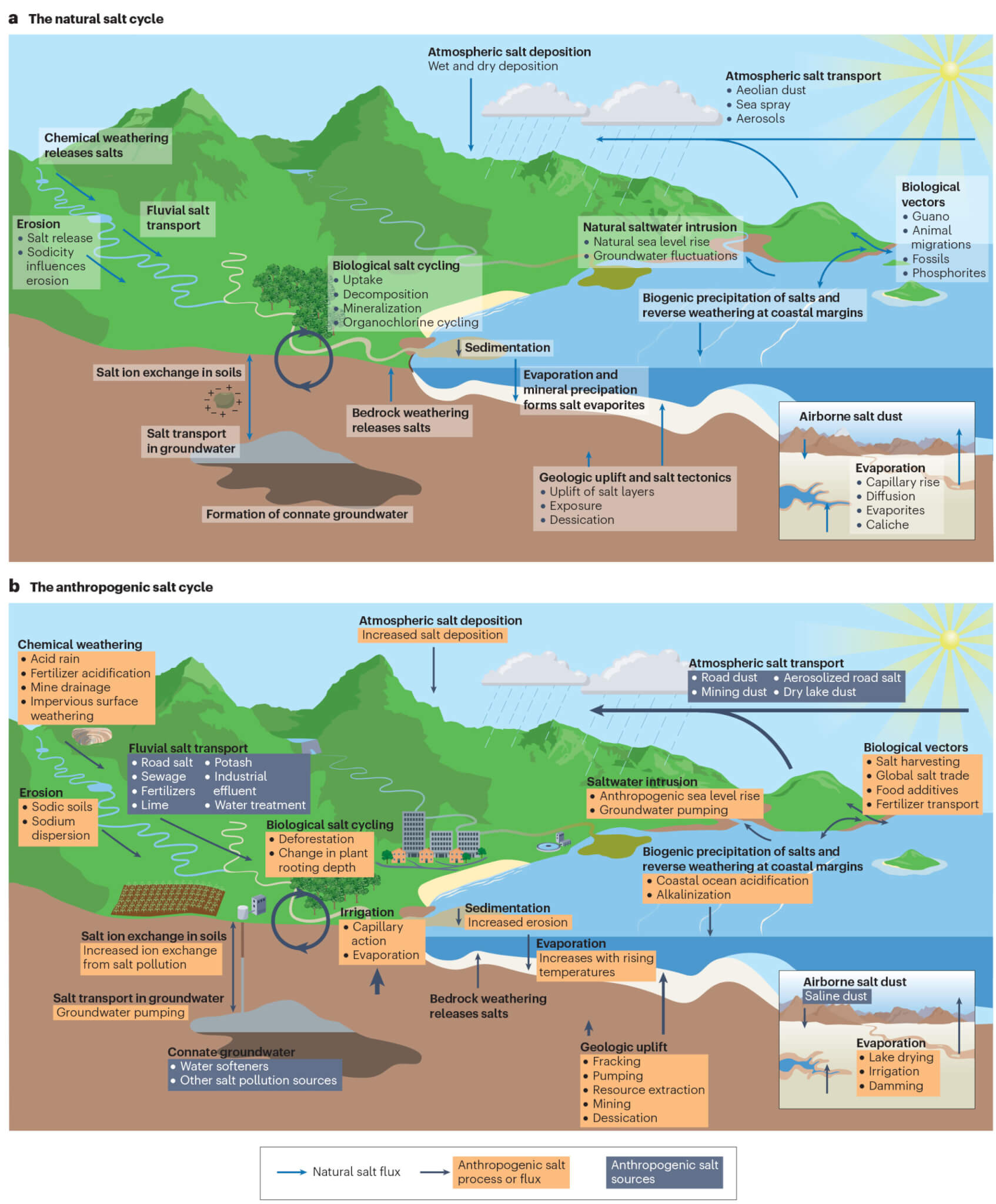

While geologic and hydrologic processes naturally introduce salts to Earth’s surface over time, human actions such as mining, land development, agriculture, and industrial activities are rapidly accelerating this natural “salt cycle.” These human-induced changes can harm biodiversity and even render drinking water unsafe in extreme cases.

“If you think of the planet as a living organism, when you accumulate so much salt it could affect the functioning of vital organs or ecosystems,” says study author Sujay Kaushal, a geology professor who holds a joint appointment in UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, in a university release. “Removing salt from water is energy intensive and expensive, and the brine byproduct you end up with is saltier than ocean water and can’t be easily disposed of.”

The study introduces the concept of an “anthropogenic salt cycle,” indicating that humans are now influencing the concentration and cycling of salt on a global scale.

“Twenty years ago, all we had were case studies. We could say surface waters were salty here in New York or in Baltimore’s drinking water supply,” says study co-author Gene Likens, an ecologist at the University of Connecticut and the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. “We now show that it’s a cycle — from the deep Earth to the atmosphere — that’s been significantly perturbed by human activities.”

The study considers various salt ions present underground and in surface water. Salts consist of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, with commonly found ions including calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sulfate.

“When people think of salt, they tend to think of sodium chloride, but our work over the years has shown that we’ve disturbed other types of salts, including ones related to limestone, gypsum and calcium sulfate,” explains Kaushal.

In higher concentrations, these ions can cause environmental issues. The study reveals that human-induced salinization has affected approximately 2.5 billion acres of soil worldwide, an area equivalent to the size of the United States. Salt ions have also increased in streams and rivers over the past half-century, coinciding with the global rise in salt use and production.

Salt contamination has even reached the atmosphere, as drying lakes in some regions release plumes of saline dust. In snowy areas, road salts can become aerosolized, forming sodium and chloride particulate matter.

The repercussions of salinization extend to “cascading” effects, such as the accelerated melting of snow in regions relying on snowmelt for their water supply. Salt ions can also bind to contaminants in soils and sediments, creating “chemical cocktails” that circulate in the environment, posing harm.

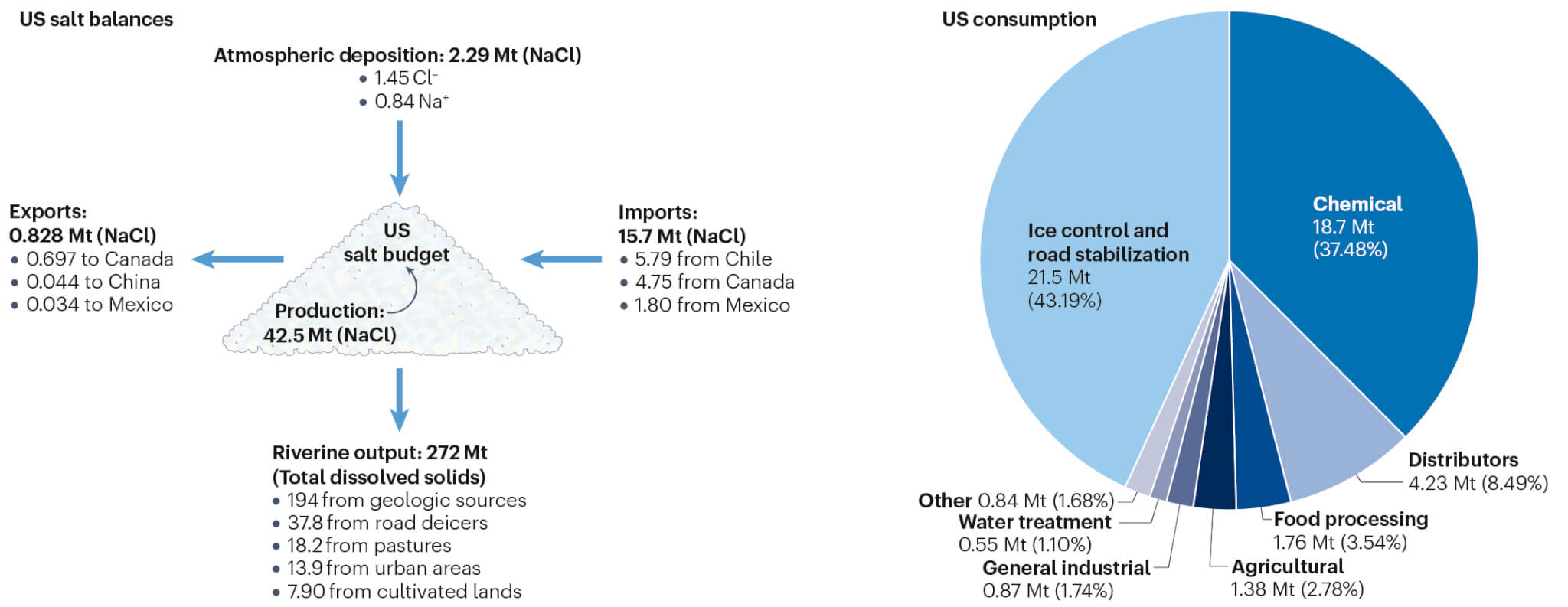

In the U.S., road salts play a significant role, with the country producing 44 billion pounds of de-icing agents annually. Road salts accounted for 44 percent of U.S. salt consumption between 2013 and 2017 and contributed to 13.9 percent of the total dissolved solids in streams nationwide, leading to substantial salt concentration in watersheds.

To mitigate the risk of excessive salt entering U.S. waterways, Kaushal recommends policies that either limit road salt use or promote alternatives. Several U.S. cities, including Washington, D.C., have started using beet juice as a less salty alternative for de-icing roads.

“There’s the short-term risk of injury, which is serious and something we certainly need to think about, but there’s also the long-term risk of health issues associated with too much salt in our water,” notes Kaushal. “It’s about finding the right balance.”

The study’s authors also propose establishing a “planetary boundary for safe and sustainable salt use,” similar to the boundaries set for carbon dioxide levels to combat climate change.

“This is a very complex issue because salt is not considered a primary drinking water contaminant in the U.S., so to regulate it would be a big undertaking,” says Kaushal. “But do I think it’s a substance that is increasing in the environment to harmful levels? Yes.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

You might also be interested in:

- Pass the salt, it can actually be healthy for you

- Why do icicles have ripples? Scientists say it’s all about salt

- Hold the salt for a longer life? Why opting for other seasoning could add years to your lifespan

Everything we do is wrong. It all kills nature and no doubt causes climate change.

The article mentions mining, road salt, and agriculture. And yet the headline talks about “our obsession with seasoning.” Did the writer of the headline read the article? Or did they just ignore it in favour of the most click-bait worthy option going?

The most abundant element on earth, and we’re not supposed to use it. But moron on came up with this study?