BOSTON — One of the world’s oldest sea creatures dating back half a billion years has been unearthed in a desert in Utah. The oldest sea squirt ever found on Earth was discovered in an area known as the Badlands. Its remains were found in a prehistoric graveyard renowned for preserving soft-bodied animals.

The sea squirt, or tunicate, belongs to a wonderfully diverse group of marine invertebrates that share a distant relation to mammals. Their modern counterparts are found worldwide, from polar regions to the tropics, floating freely in the water or anchored to surfaces like rocks, docks, and ship hulls. These creatures earned the name “sea squirts” because they react to touch by tensing up and expelling water from their siphons.

The Badlands National Park is renowned for having one of the world’s richest fossil beds, providing an invaluable resource for scientists studying the evolution of various mammalian species, such as horses, rhinos, and saber-toothed cats.

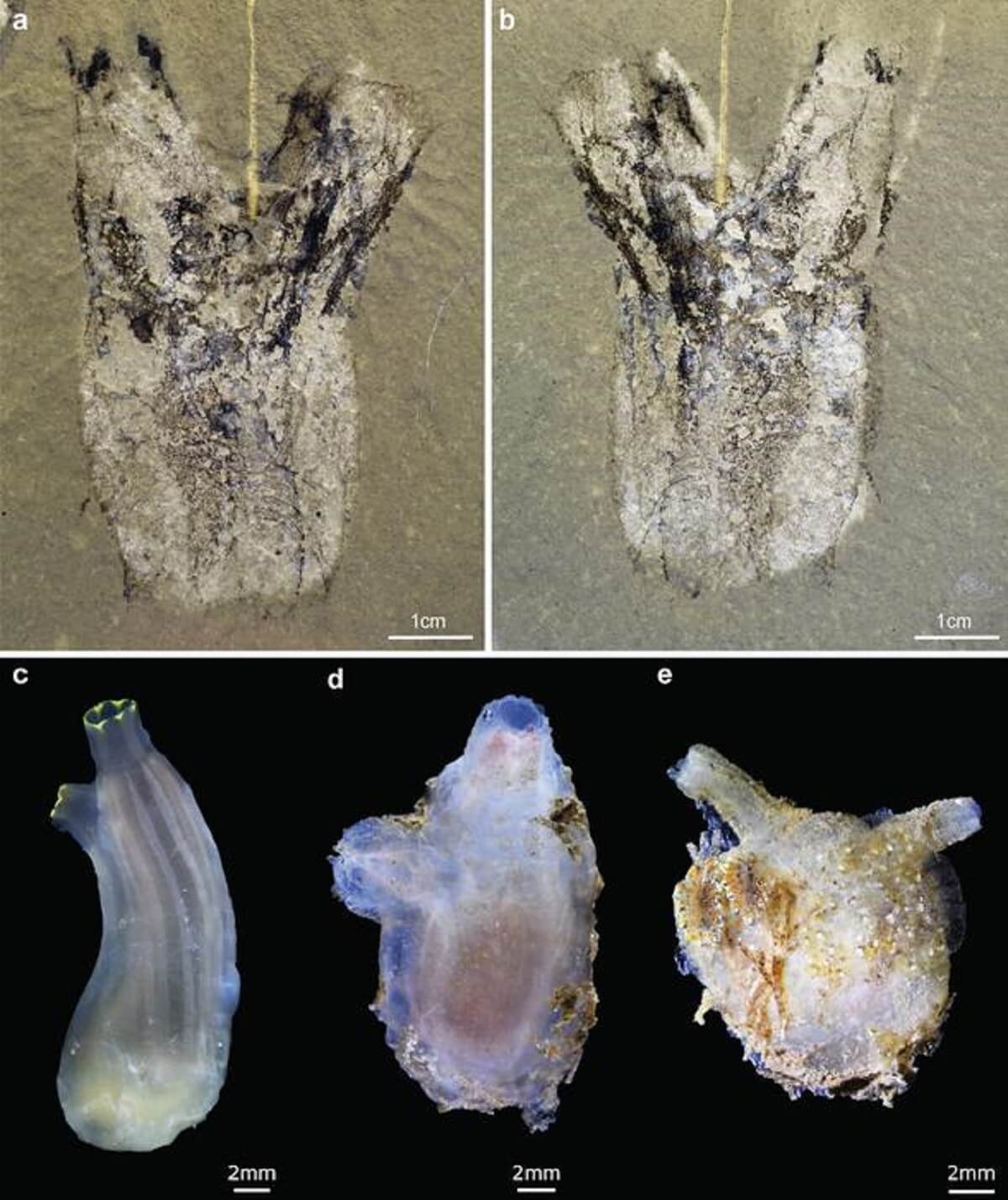

(credit: Rudy Lerosey-Aubril (a,b) and Karma Nanglu (c,d,e))

“This animal is as exciting a discovery as some of the stuff I found when hanging off a cliffside of a mountain, or jumping out of a helicopter. It’s just as cool,” says Dr. Karma Nanglu, the lead author and postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, in a media release.

The fossilized creature, named Megasiphon thylakos, dwelt on the seafloor during the Cambrian era, a period of rapid evolution when most major animal groups first appeared on Earth. The animal underwent a remarkable transformation from a tadpole-like larva to a stationary, filter-feeding adult. One of its siphons drew in water laden with food particles, which the creature filtered internally. Once feeding was complete, the other siphon expelled the water.

“This idea that they begin as tadpole-looking larva that, when ready to develop, basically headbutts a rock, sticks to it, and begins to metamorphosis by reabsorbing its own tail to transform into this being with two siphons is just awe-inspiring,” adds Dr. Nanglu.

Tunicates are the closest invertebrate relatives to vertebrates, a group that includes fish, mammals, and humans. Despite their importance in understanding our evolutionary history, they are nearly absent from the fossil record.

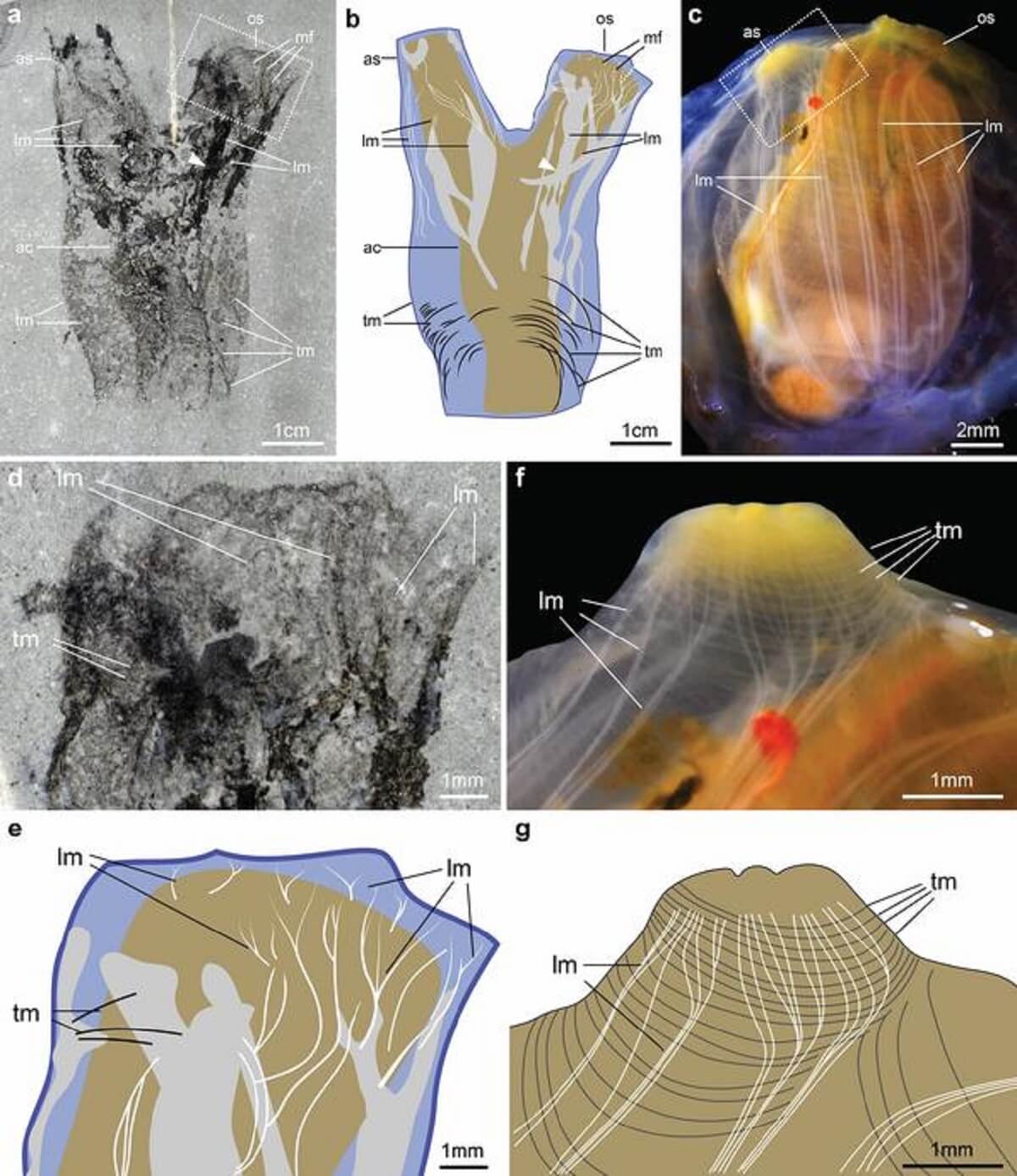

The research team was particularly struck by the dark bands running up and down the body of the Megasiphon fossil. High-resolution images of the fossil allowed the researchers to draw comparisons with a modern counterpart called Ciona. The striking similarities between Ciona’s siphon-opening muscles and the fossil’s dark bands were evident.

“Megasiphon’s morphology suggests to us that the ancestral lifestyle of tunicates involved a non-moving adult that filter fed with its large siphons,” explains Dr. Nanglu. “It’s so rare to find not just a tunicate fossil, but one that provides a unique and unparalleled view into the early evolutionary origins of this enigmatic group.”

(credit: James Wheeler (a,d) and Karma Nanglu (b,c,e,f,g))

To date, Megasiphon thylakos is the only known tunicate fossil with soft tissue preservation. It is currently displayed at the Utah Museum of Natural History.

“The close morphological similarity of Megasiphon with modern tunicates was simply too striking to overlook, and we immediately knew that the fossil would have an interesting story to tell,” says Professor Javier Ortega-Hernandez, a co-author of the study.

At 500 million years-old, Megasiphon provides the clearest glimpse yet into the anatomy and early evolutionary history of ancient tunicates. The fossil serves as a testament that most of the modern body plan of tunicates was already established shortly after the Cambrian Explosion.

“This is an incredible find as we had virtually no conclusive evidence for the ancestral modes of life for this group before this,” adds Dr. Nanglu.

During the Cambrian period, Utah was located near the equator, resulting in warm water temperatures. The combination of warm, shallow water and nutrient-rich silt fostered a highly diverse marine fauna.

The researchers, having collected hundreds of new fossils this spring, believe that the site, known as the Marjum Formation, has only begun to reveal its secrets.

The discovery of Megasiphon is detailed in the journal Nature Communications.

You might also be interested in:

- How did the Earth make continents? Scientists debunk a popular explanation

- Billion-year-old fossil sheds light on origin of animals, scientists say

- World’s oldest meal dating back 550 million years discovered in our animal ancestors

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.